At first no one noticed the children as they sat quietly in the Butte-Silver Bow County Courthouse. The six Freedman children, ages eight to fifteen, had filed in with their mother early that morning in 1938. Recently divorced from her husband and earning little in her job as a research editor, Alice Freedman was overwhelmed. Before leaving the children, she told them to wait for her return. As the day wore on, county workers noticed the children. At noon they bought them lunch and contacted the juvenile court. That evening, the Freedman children were taken to a local receiving home. Within two weeks, they were committed to the state orphanage and on their way to the facility in Twin Bridges.

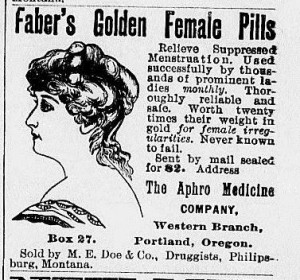

Similar scenarios had played out for the thousands of other residents of the Montana State Orphanage. Most, like the Freedman children, were not true orphans, but rather “orphans of the living,” from homes shattered by devastating poverty, turbulent parental relationships, substance abuse, poor parenting skills, or physical and emotional abuse. In the absence of local, state, or federal social welfare programs, the state orphanage was one of the few options available to these children and the destitute women who could no longer care for them.

Between 1894, when the facility opened, and 1975, when legislative cuts forced its closure, the Montana State Orphanage housed over five thousand children. Established to provide “a haven for innocent children whose poverty and need might lead to lives of crime,” the orphanage was designed along nineteenth-century lines to prepare children for productive adult lives by segregating them and providing them with food, education, vocational training, and a rigid structure.

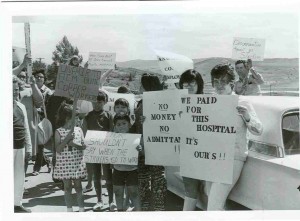

However, even as the orphanage’s first building, a sprawling Victorian structure known as “The Castle,” was being completed, attitudes toward needy children were changing. By the early 1900s, Progressive Era reformers began arguing that orphanages were dehumanizing and rife with abuse. Children, they claimed, needed a healthy home life, with their parents, if possible, or, if not, with a worthy foster family. To achieve this goal, they advocated the creation and expansion of government agencies to address the needs of abandoned, abused, or widowed women and their children.

Continue reading There’s No Place like Home: The Role of the Montana State Orphanage