In late August and early September of 1927, Daniel Slayton, a Lavina, Montana, businessman and farmer, lay dying of bone cancer. During the final three weeks of his life, he spent no moment alone. Daughters, daughters-in-law, his cousin Mary, the community midwife, a nurse hired from Billings, and Slayton’s wife, Lizzie, cared for him and kept vigil. Though Slayton’s adult sons had earlier helped him seek treatment and, in the end, came to say their goodbyes, the women in his life mostly watched over him in his final hours.

In serving as family caregivers, Montana women have joined a legion of women across time. Before 1900, hospitals typically cared for soldiers, the poor, and the homeless. On Montana’s frontier, where single men far outnumbered women, churches underwrote Montana’s earliest hospitals. Soon self-supporting matrons converted boardinghouses into private hospitals. In the first half of the twentieth century, Montana pest houses, poor farms, and finally, state institutions such as the Montana State Tuberculosis Sanatorium at Galen provided some long-term care for Montanans without families. Nevertheless, a family’s women—its mothers, wives, sisters, aunts, daughters, and cousins—typically assumed responsibility for the care of relatives. Into the 1960s, and beyond, women performed this work out of necessity, longstanding tradition, and often love.

Caregiving has always been hard work, especially when added to the routine domestic labor that kept homes and farms going. Although the Slaytons had enough money to hire laundry and chore help in 1927, they were otherwise struggling financially. To further their income, they boarded schoolteachers who arrived in the final weeks of Daniel’s life. A haying crew came through as usual in late August and expected meals—a task that Daniel himself had often managed. All extra family members and caregivers needed feeding too. In other words, hectic household patterns—including financial worries—continued throughout Daniel’s final illness.

Until Daniel’s cancer emerged, the couple had worried more about Lizzie’s health. She was sixty-nine and struggling with rheumatism and other illnesses. Her frailness may explain why the family hired Eunice Randall once Slayton became bedridden. Though called a midwife, Randall, like Rose Gordon in White Sulphur Springs, also worked as a private community home health aide, attending to recuperations, births, and deaths. Randall took over the more difficult and distasteful parts of nursing—enemas and poultices, for instance. Then, as Daniel struggled with intense pain, the family hired a trained private duty nurse, Harriet O’Day, from Billings.

Still, Daniel relied on Lizzie for comfort, conversation, prayer, singing, attention to legal details, and companionship. At the end of August, Lizzie began keeping Daniel’s forty-year diary current. For a few days, she wrote in Daniel’s voice, but soon observed and recorded Daniel’s approaching death in her own, noting when his limbs grew cold, when he slept more, as well as when she took to her own bed, “played out” with exhaustion.

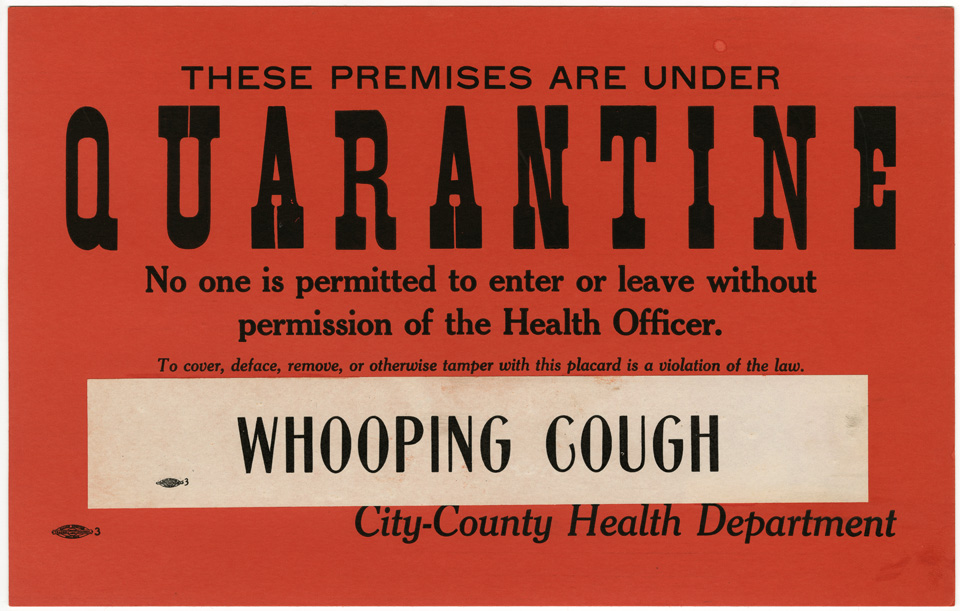

Montana Historical Society Collection, X1969.18.16

This scene has a thousand variations. In 1887, Montana pioneer Pamelia Fergus died of metastasized breast cancer on a hospital bed in her daughter Luella’s Helena parlor, while husband James tended ranch business near Fort McGinnis and son Andrew sold cattle in Chicago. In fact, her daughter had overseen Fergus’s mastectomy in the same bed a year earlier. In 1923, in the southeastern Montana coal boomtown of Bearcreek, twelve-year-old Rose Naglich cared for her dying mother. “I missed a lot of school,” Rose remembered, “in order to care for my mom and to help with the cooking and taking care of the kids.” Rose, whose father already had miners’ consumption, endured enormous emotional loss as well: “I cried while my mother held me in her arms. I knew she was going to die, and there was nothing I could do.”

Daniel Slayton died the night of September 8, 1927. Nurse O’Day called the family to his bedside as he slipped away. Lizzie read him Psalm 103 and sang “Simply Trusting Every Day.” At his death, the three weeks of “night watching,” administering pain medicine, being present to Daniel’s requests, and supervising all household activities ended for the ensemble of women—aided by his sons—who’d attended him so closely. The women of Lavina, already generous in small gifts and visits, rallied the next day, bringing doughnuts, providing supper for the boarding teachers, and offering help with funeral preparations.

At no point during Slayton’s dying months, did Lizzie, her daughters, other family members, or the community question the gift and obligation they faced in caring for Daniel. Across Montana, across time, women like those of the Naglich, Fergus, and Slayton families carried out that same attendance. They orchestrated their vigils and the intense demands of nursing around daily routines, outside work, children, financial straits, and their own emotional and physical travails to provide succor in illnesses that ended joyfully in good health or with grief, and relief, in death. MSW

Sources

McFarland, Rose Naglich. “Rose’s Story.” In MHA Ventures, Senior Reflections: Montana’s Unclaimed Treasure. Helena: Sweetgrass Books, 2002.

Nickel, Dawn Dorothy. “Dying in the West: Health Care Policies and Caregiving Practices in Montana and Alberta, 1880-1950.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 2005.