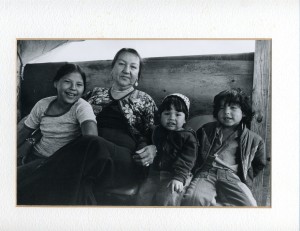

“We in the Native American community know that the warrior of old no longer exists. So we ask ourselves, ‘What do we have left?’ We have individuals who are culturally aware, who realize the value of getting a ‘white man’s education’ and utilizing that to the benefit . . . of the community. They have the ability to turn this whole negative picture of cultural genocide around.” Bonnie HeavyRunner spoke these words in praise of her sister, Iris HeavyRunner, but she could have been describing herself.

One of thirteen children, Bonnie HeavyRunner grew up in Browning on the Blackfeet Reservation, where she experienced the daily reality of poverty, relatives struggling with alcohol addiction, and the sudden loss of family members. At a young age she vowed to stay sober and remain true to her cultural values. Her personal integrity became the foundation of her determination to improve the lives of American Indian people by being an advocate for Native and women’s issues while building cross-cultural bridges. As the director of the University of Montana’s Native American Studies program, she worked tirelessly to bring about greater cultural awareness of American Indians while making the academic world more hospitable to Indian students.

HeavyRunner earned a bachelor’s degree in social work from the University of Montana in 1983 and then a law degree in 1988. One of only a few women in the School of Law in the 1980s, HeavyRunner was also the only American Indian law student in her class. She went on to become a clerk, and then a judge, on the Blackfeet Tribal Court, but she did not forget the cultural isolation she had felt at the university. Many Native students dropped out of school because they experienced such a wide gap between themselves and the non-Indian culture of the university community at large. HeavyRunner wanted to change that. Continue reading Bonnie HeavyRunner: A Warrior for Diversity