“Some say basketball is a metaphor for life,” mused NBA Hall of Fame coach Phil Jackson during an interview about Montana’s Class C girls’ basketball tradition, “but it’s bigger than that. It’s . . . joy.”

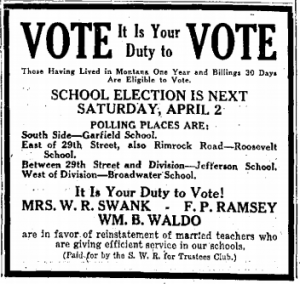

For the first half of the twentieth century, Montana’s young female basketball players knew that joy—sprinting full court in front of enthusiastic crowds. In 1904, ten girls from Fort Shaw Indian School drew enormous Great Falls crowds and beat all rivals at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Phil Jackson’s mother captained her 1927 Wolf Point girls’ basketball team. Patricia Morrison’s 1944-45 Fairfield High girls’ team beat the boys, playing boys’ rules.

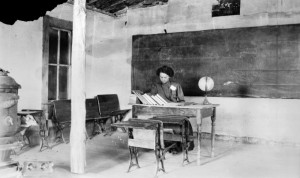

But by 1950, mainstream sensibilities and school funding limits had corralled Montana’s exuberant female athletes. Their opportunities became limited to tamer intramural activities—often characterized by cast-off equipment, unskilled coaching, and poor facilities. It took congressional action and a court fight to bring equal opportunity in all sports to Montana’s young women athletes.

The question, of course, was never about girls’ physical prowess or fearlessness. Instead, the issue was equal access to resources. In response, Congress enacted the Education Amendments of 1972. These regulations covered many educational issues, but the best-known section reads, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Though it prohibited gender discrimination in all areas of education, Title IX’s most far-reaching impact occurred in women’s sports.

Continue reading Fighting for Female Athletes: Title IX in Montana