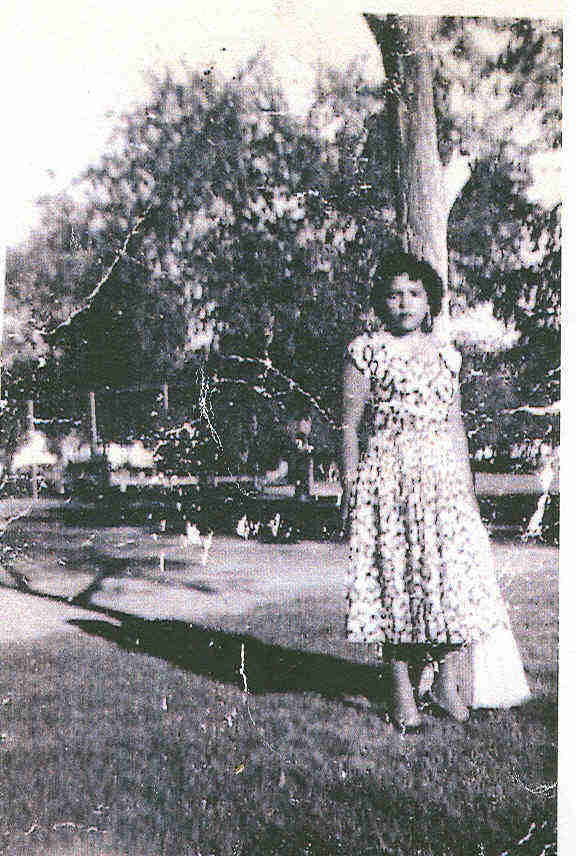

Born to Mexican immigrants Petra Ortega and Fidencio Acebedo in 1922, Lula Martinez grew up in Butte but left as a teenager for agricultural work in the Pacific Northwest. She returned over forty years later to work on behalf of the city’s impoverished and unemployed. Her memories of her childhood in Butte reveal the complex racial dynamic that existed in the mining city in the early twentieth century, and her experiences as an ethnic minority instilled a lifelong commitment to community activism and female empowerment.

Martinez’s father worked construction on the railroad, and his job took the family from Texas to Montana. The Acebedos settled in Butte, and Fidencio worked in the mines. The Acebedos were part of Butte’s small but significant Hispanic population, drawn to the booming copper mines in the first decades of the twentieth century. By World War II, “several hundred Mexicans and Filipinos” lived in Butte. The majority of the Mexican immigrants worked at the Leonard Mine and lived on the city’s east side. Unlike Filipinos, who encountered violence in the mines and tended not to stay, Mexican workers seem to have been generally accepted by the other miners, and Mexican families did not live in segregated neighborhoods. Martinez recalled that growing up “we were surrounded by different nationalities. We had Vankoviches and Joseviches and Biviches, and we had Serbians, and we had Chinese. We had italianos, españolas, and Mexican people. We had the whole United Nations around on the East Side.”

In spite of this ethnic diversity, Martinez did encounter discrimination. As she got older, and especially after she began to attend school, it became clear that she was trapped in a racial hierarchy that discriminated against Mexicans and Mexican Americans. She remembered, “As children we didn’t know there was a difference so we got along fine. It was when you’re . . . going to school when the teachers started to say, ‘well you gotta sit over there. All the Mexicans sit on that side.’ . . . [A]nd then we found out that there was a difference.” Martinez’s encounters with racism in her childhood instilled a determination to work for social justice, but they also gave her a “hatred” of Butte that she carried with her into adulthood.

Fidencio Acebedo died in a mining accident in 1928, leaving his wife to raise five children. She remarried Juan Aguilar, a Mexican immigrant who could not read or write English. (Later, Aguilar would also die in the mines.) Martinez credits her mother as a role model for helping others. Petra Aguilar took in boarders even if they could not afford to pay, and she fed neighbors and transients who came through on the train. Martinez recalls that her mother “never gave up. At the time that my dad got killed in the mine, she got a pension [from] the mine. . . . [S]he’d feed everybody. She’d make big pots of stew and feed all the kids. . . . [M]y mother influenced me by . . . my seeing . . . that she never judged.”

Martinez left Butte when she was seventeen to pick apples in Washington. As an adult she became deeply involved in community organizations that served agricultural workers. Her efforts ranged from collecting food commodities to starting health clinics to organizing advocacy groups to help migrant workers collect social services.

Martinez’s activism was based in part on her particular brand of feminism that linked womanhood to community betterment. Although raised to follow traditional gender roles in which women kept the home, Martinez saw women as uniquely suited to solve problems in the greater community. She believed that “a woman is the strongest” member of the family. Motherhood, in particular, gave women insights into community problems: “[I]t’s women who know how much they need when their children get sick. It’s women who know that without a good health clinic or good doctor, they’re the ones that suffer. Their children suffer.”

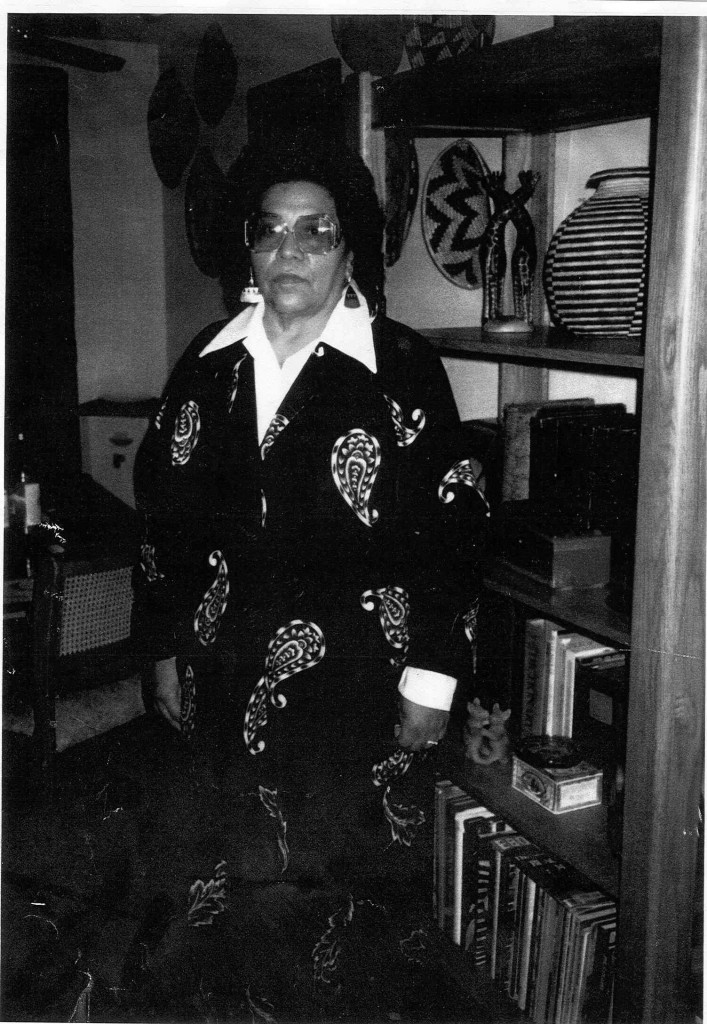

In 1984, at age sixty-two, Martinez decided to return to the hometown that she had abandoned as a teenager. She brought her skills as an activist and her insights into racial and class prejudice and began working as an organizer for the Butte Community Union, a group formed to advocate for the city’s lower classes. At BCU, Martinez campaigned for better conditions in public housing and access to affordable heat, among other issues. Sister Kathleen O’Sullivan, a BCU board member, described Martinez as the “wisdom person at BCU.” Sullivan also noted that Martinez was a highly effective organizer: “she spoke truth, not trying to convince people, but would say something that would focus the discussion, draw your attention to the essence of something.”

Martinez left Montana in 1988 to be closer to family in Portland, but her return as an adult had shifted her opinion of Butte. Although she never learned to love the city as ferociously as some, she did come to love the community: “[A]nytime you make friends, long-lasting friends, you’ve won. . . . I’ve learned a lot by being here these last years, more about Butte than I did before I left. . . . The hate isn’t there but it’s still not . . . a love of Butte. It’s the love of people.” AH

Sources

Basso, Matthew L. Meet Joe Copper: Masculinity and Race on Montana’s World War II Home Front. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Finn, Janet. Mining Childhood: Growing Up in Butte, Montana, 1900-1960. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2012.

Martinez, Lula. Interview by Laurie Mercier, Portland, Ore., September 1987. OH 1017, Women as Community Builders Oral History Project, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

__________. Interview by Teresa Jordan, Butte, Mont., April 2, 1986. Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives.

Mercier, Laurie. “’We’re All Familia’: The Work and Activism of Lula Martinez.” In Motherlode: Legacies of Women’s Lives and Labors in Butte, Montana. Ed. Janet L. Finn and Ellen Crain. Livingston, MT: Clark City Press, 2005, 268-77.

__________. “Creating a New Community in the North: Mexican Americans of the Yellowstone Valley.” In Montana Legacy: Essays on History, People, and Place. Ed. Harry W. Fritz, Mary Murphy, and Robert R. Swartout. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2002.

This is my family!

What great story; this strong woman helped people to move forward; God bless this woman. Thanks for your strong courage. Thank you Lula Martinez ; Robert Lee Contreras