In the fall of 1913, Jennie Bell Maynard, a teacher in Plains, married banker Bradley Ernsberger. The couple kept their wedding a secret until Bradley found a job in Lewistown and they moved: “No inkling of the marriage leaked out. . . . Mrs. Ernsberger continued to use her maiden name and teach school.” A year later, Butte teacher Adelaide Rowe eloped to Fort Benton with her sweetheart, Theodore Pilger. They hid their marriage for three years. Maynard and Rowe were just two of the many Montana women teachers who married secretly—or didn’t marry at all—in order to keep teaching.

The story of “marriage bars,’ or bans, does not unfold linearly. Livingston lifted its “rule against the employment of married lady teachers” in 1896. The Anaconda school district also allowed married women to teach in the 1890s, but in 1899, facing lower than anticipated enrollment, the superintendent sought the resignation of the district’s one married teacher, explaining that Mrs. Foley “is married and is not in need of the salary which she draws from the schools.”

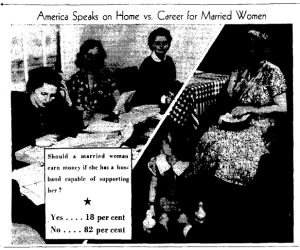

The idea that married women did not need the income, and that “hiring married women would deprive single girls of opportunities,” was the most common rationale for marriage bars. On the other hand, advocates for married teachers tried unsuccessfully to reframe the debate in terms of student welfare. Mrs. W. J. Christie of Butte argued in 1913 that “The test of employment should be efficiency and nothing else.” Mrs. James Floyd Denison agreed: “When a married woman has the desire to go from her home and to enter the school room . . . it must be because her heart and soul are in the teaching work. Under those circumstances, if she is allowed to teach, the community will be getting her very best service.” Unconvinced, Miss Ella Crowley, Silver Bow County superintendent of schools, believed that a married woman’s place was at home. While she recognized the value of experience, she also believed that if women taught after marriage, “there never would be any room for new teachers or for girls.”

Unlike urban districts, country schools, desperate to fill lower-paid positions, generally welcomed married teachers. In 1924, when Lilian Peterson, a widow with six children, could not find a job in Kalispell or Missoula because their marriage bars extended to widows with children, she signed on at Pine Grove School northeast of Kalispell. Likewise, Maggie Gorman Davis, who homesteaded with her husband, Dennis, in Choteau County, taught in the four-teacher Carter School in 1911 to supplement their income.

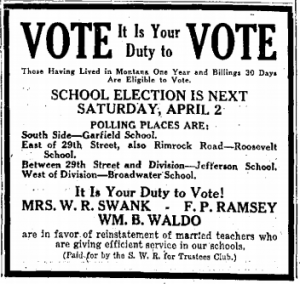

While some districts banned all married teachers, others were willing to employ married women if their husbands were “an invalid in some way.” Commenting on the Billings school board’s decision to institute a marriage bar in 1927, the editor of the Helena Independent argued that exceptions should be made for “married women whose husbands are invalids or insane and unable, therefore, to provide a living for the family.” Nevertheless, he averred that men should take care of their wives. “Single women with their living to make should not be penalized by having positions open to them otherwise taken by women who have married failures.”

Unsurprisingly, attitudes toward married teachers changed during World War II, with most schools welcoming married women back to the classroom. In 1942, M. P. Moe, the secretary of the Montana Education Association, stated that “1,500 married teachers are in the schools ‘for the duration only.’” However, advocates for married women teachers, including the National Education Association, published several editorials asking school boards to remember married teachers after the war, arguing that if they “were good enough . . . in wartime . . ., they’re good enough in peace time.”

Most, but not all, Montana school districts took this message to heart—helped along by the demand for teachers during the postwar baby boom. The Billings school board lifted its ban against women teachers in 1953, encouraged by the superintendent who explained that he expected teacher supply to outstrip demand indefinitely. In districts facing declining enrollment or decreasing revenue, however, discrimination continued. In 1953, the Bigfork school board adopted two salary schedules, one for single teachers and a second, lower scale for married women teachers whose husbands worked. “Ideally,” Superintendent C. E. Naugle explained, “everyone would be treated in the same manner. However, we are not dealing with an ideal situation, we are dealing with reality,” and cuts should be made “where it will hurt the least.”

In 1955, Montana attorney general Arnold Olsen declared that “Marriage is not a ground for dismissal” and that “teacher contracts could not discriminate against married teachers.” Even so, as late as 1964, the superintendent of the Anaconda school district reassured angry residents—worried that single teachers lacked opportunities—that both the district and the Anaconda Teachers Union supported hiring single women and married men over married women. In fact, married women were only offered contracts when qualified single (or male) teachers were unavailable.

Ultimately, the 1964 Civil Rights Act ended discrimination against married women teachers. By outlawing discrimination based on sex, the act forced local school districts to treat married female teachers as they treated their married male counterparts. At last, boards began to follow the course education reformers had recommended fifty years earlier: basing their hiring decisions on ability alone. MK

Learn more about the experiences of Montana’s rural women teachers in “Be Creative and Resourceful”: Rural Teachers in the Early Twentieth Century.

Sources

Cooke, Dennis H., W. G. Knox and R. H. Libby. “Local Residents and Married Women as Teachers.” Review of Educational Research 13, no. 3 (June, 1943), 252-61.

Goldin, Claudia. “Marriage Bars: Discrimination against Married Women Workers from the 1920s to the 1950s” in Favorits of Fortune: Technology, Growth, and Economic Development since the Industrial Revolution. Higonnet, Patrice, David S. Landes, and Henry Rosovsky, ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991, 511-36.

Kohl, Martha. I Do: A Cultural History of Montana Weddings. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2011.

Kohl, Seena. “‘Well I Have Lived in Montana Almost a Week and Like It Fine’: Letters from the Davis Homestead, 1910-1926.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 51, no. 3 (Autumn 2001), 32-45. Download here.

Rankin, Charles E. “Teaching: Opportunity and Limitation for Wyoming Women.” Western Historical Quarterly 21, no. 2 (May, 1990), 147-70.

Women in Education, Discrimination. Vertical file, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Career women have too much to lose by getting married since they will only want the very best of all and will never ever settle for less. Very money hungry women everywhere nowadays unfortunately.

You kind of sound like a communist. People shouldn’t pursue their own economic betterment?

Gotta agree with JL here. “Money hungry” seems like an empty term you’re using to make your point more valid. Prioritizing financial health just seems like common sense to me.

I would think a lot of people, especially progressives, would like the idea of giving jobs to those who need it the most first. There is something to be said for that.