Judy Smith was a fixture in Montana’s feminist community from her arrival in the state in 1973 until her death in 2013. Her four decades of activism in Missoula encapsulated the “second wave” of American feminism.

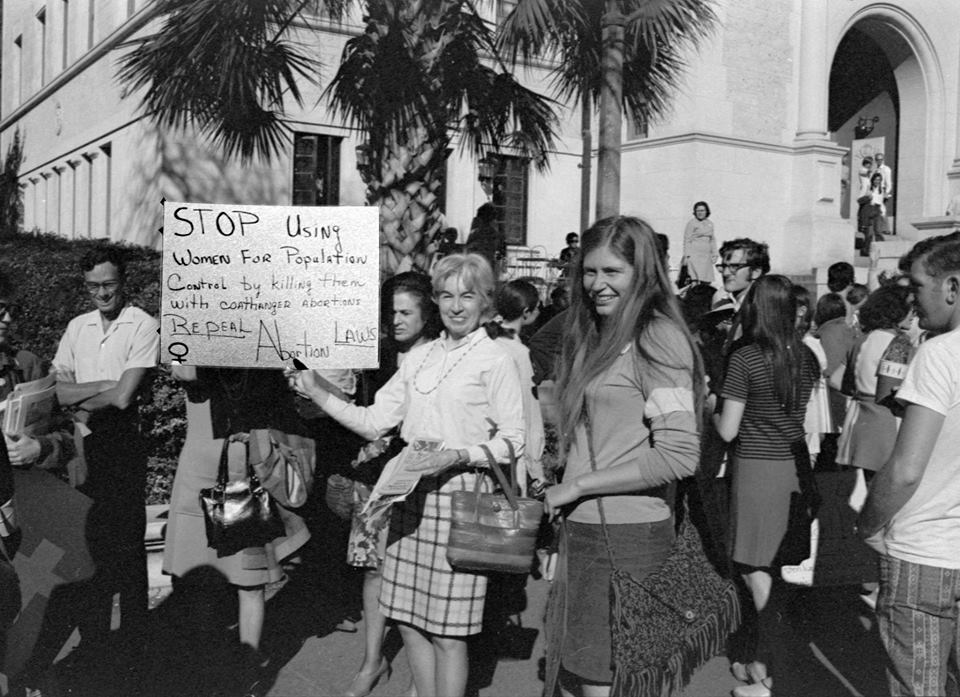

Like many of her contemporaries, Smith followed the “classic” trajectory from the student protest, civil rights, and anti-Vietnam War movements of the 1960s into the women’s movement of the 1970s. While pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Texas, Smith joined a reproductive rights group. Because abortion was banned in the United States, she sometimes ferried desperate women over the border to Mexico to procure abortions. Knowing her actions were illegal, Smith consulted a local lawyer, Sarah Weddington. These informal conversations sparked the idea of challenging Texas’s anti-abortion statutes, culminating in the landmark Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade. From this success, Smith learned that “any action that you take . . . can build into something.”

Smith brought her conviction that grassroots activism was the key to social change with her to Missoula. As she later characterized her approach, she simply looked around her adopted hometown and demanded: “What do women need here? Let’s get it going. Get it done.” Continue reading Feminism Personified: Judy Smith and the Women’s Movement