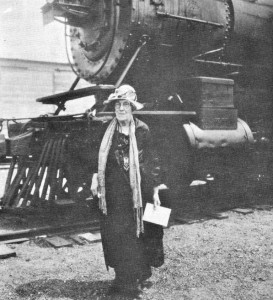

Martha Edgerton came to Bannack as a teenager in 1863. As a teacher, musician, wife, mother of seven, clubwoman, and leader in the women’s suffrage movement, she successfully balanced traditional gender roles with an active public life. Widowed young, she entered the workforce, becoming the first woman editor of a Montana daily newspaper, a local and state leader in the Montana Socialist Party, and a prolific writer. Hers was a long life of striking achievements.

Edgerton was thirteen when she arrived in Bannack in 1863 after her father was appointed governor of Idaho Territory. Two years later, the family returned to Ohio, and she subsequently enrolled at Oberlin College to study music. Later, while teaching at the Ohio Institute for the Blind in Columbus, she met and married Herbert P. Rolfe. In 1876, the couple moved to Helena, where Herbert became the superintendent of public schools. Herbert and Martha Rolfe were kindred spirits: passionate advocates for equality of African Americans, women’s suffrage, and the rights of the workingman.

Their activism eventually took them to Great Falls, where, in 1884, the Rolfes took out a homestead right outside the city, which had been newly surveyed and platted by Herbert himself. Four years later, Herbert—long a Republican Party activist—established The Leader, a newspaper designed to counter the influence of Great Falls founder Paris Gibson’s Democratic Tribune. Though occupied with home-schooling the couple’s seven children, Martha also wrote for The Leader and stayed closely involved in her husband’s political crusades.

The Panic of 1893 erased much of the couple’s wealth. Nevertheless, the paper survived, and the Rolfes remained active in politics, including the women’s suffrage movement. Early in 1895, together with other Great Falls women, including Ella Vaughn, Josephine Trigg, and Josephine Desilets, Martha formed the Political Equality Club. The club gathered over a thousand signatures—about half of those from men— supporting women’s suffrage. Later that same year, a suffrage bill passed by over two-thirds in the Montana House, only to be tabled in the state Senate.

Within weeks of the bill’s defeat, Herbert died suddenly of typhoid, leaving Martha a widow with seven children to support. At the urging of her cousin Wilbur Fisk Sanders, she undertook the challenge of editing The Leader herself, thereby becoming the first woman to edit a daily newspaper in the state. As she remembered, “I agreed to try running a daily political paper, although absolutely ignorant of what this entailed, and never having corrected a line of proof. Thanks to the help received from printers, and those on the staff of the paper, I did not entirely fail, although some Republicans felt outraged to think that a mere woman was editing their party organ.”

Martha Rolfe operated the newspaper for the next fourteen months and, according to the Anaconda Standard, she did it well: “Since the death of the late H. P. Rolfe, Mrs. Rolfe has had absolute control of the Leader and to the surprise of many has improved that paper in many ways. She has developed real newspaper ability.”

In October 1895, Martha married The Leader’s business manager, Theodore Plassmann, who convinced her to sell the paper. When Plassmann died a few months later, Martha was left with little means of support. She described the next few years as “a nightmare I do not like to recall.” With help from Herbert’s lodge associates, she survived by undertaking a series of business ventures, including selling life insurance, writing poetry, and running a cattle ranch, though none very successful financially.

To save expenses, Plassmann moved her family from Great Falls to a small ranch near Monarch in the Little Belt Mountains. She wrote verses and sold them to Good Housekeeping magazine. When her ranch house burned to the ground, she suffered thousands of dollars in property loss, but with the help of neighbors, she rebuilt a large log home.

One day at the Monarch railway station, the agent, James M. Rector, asked Plassmann to read some political literature he kept near the ticket window. This began her conversion to socialism, which she believed “offered the best solution for many of our social ills.” She shocked Rector when she asked to join the Monarch Socialist Party, which she did, becoming its first woman member.

Later, with two of her daughters and son Edgerton, Plassmann moved to Missoula so the children could attend university. There she became a leader in the local and state socialist movement. She wrote a weekly column, “Socialist Notes,” for the Missoulian and supported the radical Industrial Workers of the World during the 1909 Missoula free-speech fight. In 1911 she even traveled to Butte to operate his office during Socialist Louis Duncan’s successful mayoral bid. Through it all, she remained a tireless advocate for women’s suffrage and rejoiced when Montana’s equal suffrage amendment passed in 1914. Two years later, on November 7, 1916, she wrote her daughter Helen: “This is a red letter day for me—I went to the polls in an auto and cast my first vote for President of the United States.”

Plassmann moved frequently during the following years, living with each of her seven children in turn. By 1920, she was settled down once again in Great Falls, where she began writing historical articles for the Great Falls Tribune and the Montana News Association, basing many of those pieces on her own experiences or on interviews with other Montana pioneers. Despite her advancing age, she continued writing until her death on September 25, 1936, at the age of eighty-six. KR

Sources

Bodkins, Sharon Lenington, comp. A Light at the End of the Canyon 1889-1989. N.p., 1989.

Calvert, Jerry W. The Gibraltar Socialism and Labor in Butte, Montana 1895-1920. Helena: Montana Historical Society, 1988.

“Editorial.” Daily Missoulian, January 4, 1914, 12.

“Mrs. Martha Edgerton Rolfe Plassmann.” Great Falls Daily Leader, October 23, 1895, 2 (originally published in the Anaconda Standard, October 22, 1895).

Plassmann, Martha. Letter to Mrs. Helen Yule, November 7, 1916. Original held by author.

__________. “Memories of a Long Life.” Unpublished manuscript held by author, copy in Great Falls Public Library.

Robison, Ken. “‘A red letter day’: Woman’s Suffrage in Montana.” Best of Great Falls, Winter, 2015.

“Socialist Notes.” Daily Missoulian, November 3, 1912, 3.

“Splendid Meeting Is Held; Equal Suffrage Club Joins with Socialist Local in Observing Day.” Daily Missoulian, March 31, 1913.

“The Struggle for Political Equality in Montana in 1895.” Great Falls River Edge, February 2005.

“Why Socialists Favor Woman’s Suffrage.” Montana Socialist, October 19, 1913, 1, 6.