In 1921, the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs (MFCWC) organized “to encourage true womanhood . . . [and] to promote interest in social uplift.” While its members engaged in many traditional women’s club activities—raising money for scholarships, creating opportunities for children, and providing aid to the sick—advancing the cause of civil rights in Montana was one of the organization’s most important legacies.

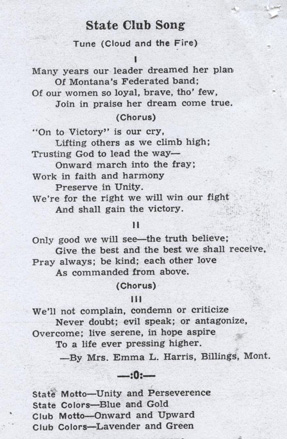

MFCWC (originally the Montana Federation of Negro Women’s Clubs) held its inaugural meeting in Butte, where members agreed on five organizing principles: “Courtesy—Justice—The Rights of Minority—one thing at a time, and a rule of majority.” At the local level, member clubs engaged in a variety of volunteer work, from bringing flowers to hospital patients to adding works by African American authors to local libraries. But at both the local and the state levels, MFCWC members also concentrated on racial politics, raising funds for the NAACP and taking positions on abolishing the poll tax and upholding anti-lynching laws.

The MFCWC’s legislative committee became especially active after World War II, and from 1949 to 1955 it led the campaign to pass civil rights legislation in Montana. The committee’s efforts reflected Montana’s complicated racial climate. As its members advocated for legislative change, the MFCWC often encountered resistance from white Montanans, who simultaneously asserted that Montana did not have a “racial problem” and that, where prejudice did exist, it could not “be changed by passing a law.”

Nevertheless, MFCWC members persevered. Between 1951 and 1955, the legislative committee worked with Montana lawmakers to introduce a bill banning segregation in places of public accommodation. The committee’s main support came from the MFCWC delegates of Cascade County, who saw the discrimination faced by African American airmen stationed at the Great Falls base. Supporters of the bill were given several talking points, ranging from the idea that Montanans “take pride in our reputation for friendliness and hospitality” to the biblical edict “love thy neighbor.” The most compelling argument advanced, however, was that segregation was especially unjust to men serving their country during wartime. Following the club’s script, one legislative proponent of the bill argued that African American soldiers “didn’t ask to be sent to Montana. But I think a man who is good enough to serve in the Army is good enough to have public accommodations.”

The civil rights bill passed the House easily in 1953 but ran up against powerful opposition in the Senate, where it died in committee. Interestingly, racial prejudice against other minority groups ultimately doomed the bill that session. Senator W. B. Spear, Jr., representing Big Horn County, headed the charge to defeat the bill. According to one observer, Spear’s position was that, “as a Senator from a county heavily populated with Indians, his white constituents would expect him to defeat any legislative attempt to enforce the extension of full rights of public accommodation to the Indians, and that his failure to do so could well result in his political death. Sufficient henchmen then rose to Sen. Spear’s bidding to jeopardize the bill.” Similarly, a Yellowstone County senator was reluctant to support the bill because of the “Mexican Problem” in his county.

The MFCWC legislative committee regrouped in 1955. This time, they recruited allies from organized labor, the Montana Farmers Union, churches, and white women’s organizations, demonstrating that segregation was not just an issue for black voters. The bill, guaranteeing “equal accommodations in public places to all people, regardless of race, creed, or color,” passed, but only after the state senate stripped the penalties for violating the law. With no enforcement mechanism, the law was mostly a symbolic victory for the MFCWC, but an important one nonetheless.

The MFCWC’s commitment to legislative change in the 1950s came at a time when the club’s membership was dwindling. Lucrative industry and armed services jobs had drawn many African Americans away from Montana in World War II, and the declining population left many of the local clubs struggling to maintain membership. In 1949 the MFCWC had only fifty members in five clubs, down from over ninety members in fifteen clubs in the mid-1920s.

By the late 1960s, racial politics was at the forefront of Americans’ social consciousness, but the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs—the group that had led the initial push for civil rights legislation in Montana—was struggling to survive. Part of the MFCWC’s decline could be attributed to African Americans’ success at integrating. By 1971, the MFCWC had become a member of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. At that time, president Marie Lacey, reflecting on the MFCWC’s fifty-year history, suggested that “Integration has limited the need for an all-black club. Junior clubs for the youthful blacks are no longer needed.” The next year, the club voted to disband, leaving as its lasting legacy its work to secure equal rights for Montana’s racial minorities. AH

Are you interested in the role women’s groups played in developing their communities? You might enjoy reading Progressive Reform and Women’s Advocacy for Public Libraries in Montana.

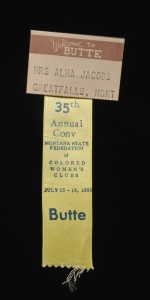

Speaking of libraries: you can read more about the life and work of librarian Alma Jacobs, whose MFCWC convention badge is pictured above, in “Alma Jacobs: Beloved Librarian, Tireless Activist.”

Sources

Arnold, Angie Mills, ed. “Montana Federation of Negro Women’s Clubs,” (1922). Copy in box 1, fldr 10, MC 281, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Behan, Barbara Carol. “Forgotten Heritage: African Americans in the Montana Territory, 1864-1889.” The Journal of African American History 91, no. 1 (Winter 2006), 23-40.

“Equal Rights Act before Senate Committee.” The People’s Voice, February 11, 1955. Copy in box 2, fldr 4, MC 281, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

“Intolerance Issue Starts Bitter Debate in House.” Great Falls Leader, February 11, 1953. Copy in box 2, fldr 4, MC 281, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Lang, William. “The Nearly Forgotten Blacks on Last Chance Gulch, 1900-1912.” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 70, no. 2 (April 1979), 50-57.

Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs records, 1921-1978. MC 281, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Riley, Glenda. “American Daughters: Black Women in the West.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 38, no. 2 (Spring 1988), 14-27.

“Senate Hits Faster Pace.” Kalispell Daily Interlake, March 3, 1955, 5.

“Unity and Perseverance . . . Our Motto.” Pre-Vue: Billings Weekly Entertainment Guide 3, no. 3 (August 1-7, 1971), 4-5, box 1, fldr 9, MC 281, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.