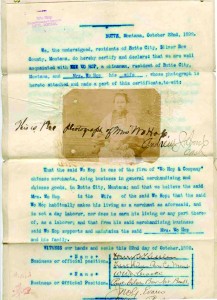

Chinese immigrants played an important role in the economic development of the West, including Montana. The 1860s mining boom and the subsequent railroad development in the region drew a diverse mix of people, including many Chinese. In spite of their role in building Montana, Chinese pioneers faced intense discrimination and their stories are often lost to history. This document is one of the few pieces of evidence we have about the life of Mrs. Wo Hop of Butte. It illustrates the precarious position of the Chinese, and especially Chinese women, in late nineteenth-century Montana.

While American businesses had welcomed—and even recruited—Chinese workers in the mid-nineteenth century, by the 1880s native-born Americans on the West Coast increasingly blamed the Chinese for unemployment and lower wages. Pressure to end economic competition, paired with the idea that the Chinese were racially inferior by nature, culminated in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The act prohibited Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States, and it was the first immigration law in American history to exclude a group based on nationality. The law allowed for the admission of certain upper-class individuals like merchants and teachers, but it was extremely difficult for these non-laborers to prove their status. Thus, until its repeal in 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act effectively ended Chinese immigration.

Mrs. Hop, whose husband was a merchant in Butte, carried these papers to prove that she was in America legally. As a Chinese woman, Mrs. Hop was in an especially dangerous position. The bulk of early Chinese immigrants to the United States were men, and Chinese women and families were seen as anomalies. The stereotype among native-born Americans was that Chinese women were brought to America as prostitutes, and religious and civic leaders promoted the idea that their presence posed a moral danger to American society. The Page Law of 1875 had imposed stiff penalties on the importation of Chinese prostitutes, and the enforcement of the law reflected a strong cultural assumption that women who immigrated from China were coming for illicit purposes.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was silent on the issue of female immigrants, leaving it for immigration agents and the courts to decide how the law would affect Chinese women coming to, and living in, America. On the one hand, Americans valued the sanctity of marriage and put a premium on the unity of families. On the other hand, the stereotype of the Chinese prostitute still colored Americans’ assumptions. As a result, Chinese women who lived here faced the constant threat of deportation unless they could prove their marital status.

A close reading of Mrs. Wo Hop’s papers reveals her tenuous legal position. They emphasize her status as a married, and thus reputable, woman whose husband “supports and maintains” her—thus allaying fears that she would become a burden to the state. They also point out that her husband “habitually makes his living as a merchant, and is not a day laborer.” By the legal standards of the Chinese Exclusion Act, these characteristics made both husband and wife “desirable” Chinese, but the fact that Mrs. Wo Hop needed to carry these papers on her person shows how uncertain life in America could be for Chinese women. – AH

Want to know more?

Learn more about the Chinese experience in Butte by reading “’Women . . . on the Level with Their White Sisters’: Rose Hum Lee and Butte’s Chinese Women in the Early Twentieth Century.”

Wives such as Mrs. Wo Hop weren’t the only Butte women who maintained a tenuous relationship with the law. Read about female bootleggers by clicking here!

Sources

Calavita, Kitty. “Collisions at the Intersection of Gender, Race, and Class: Enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Laws.” Law & Society Review 40, no. 2 (June 2006): 249-81.

—. “The Paradoxes of Race, Class, Identity, and ‘Passing’: Enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Acts, 1882-1910.” Law & Social Inquiry 25, no. 1 (Winter 2000): 1-40.

Cole, Richard P., and Gabriel J. Chin. “Emerging from the Margins of Historical Consciousness: Chinese Immigrants and the History of American Law.” Law and History Review 17, no. 2 (Summer 1999): 325-64.

Everett, George. The Butte Chinese: A Brief History of Chinese Immigrants in Southwest Montana. Butte, Mont.: The Mai Wah Society, ca. 1995.

Holmes, Krys. Montana: Stories of the Land. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2008.

Lee, Rose Hum. “Occupational Invasion, Succession, and Accommodation of the Chinese of Butte, Montana.” American Journal of Sociology 55, no. 1 (July 1949): 50-58.

Peffer, George Anthony. “Forbidden Families: Emigration Experiences of Chinese Women under the Page Law, 1875-1882.” Journal of American Ethnic History 6, no. 1 (Fall 1986): 28-46.

Stevens, Todd. “Tender Ties: Husbands’ Rights and Racial Exclusion in Chinese Marriage Cases, 1882-1924.” Law & Social Inquiry 27, no. 2 (Spring 2002): 271-305.

Swartout, Robert. “From Kwangtung to the Big Sky: The Chinese Experience in Frontier Montana.” In Montana Legacy: Essays on History, People, and Place, ed. Harry W. Fritz, Mary Murphy, and Robert R. Swartout Jr. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2002.

0 thoughts on “Discrimination: The Case of Mrs. Wo Hop”