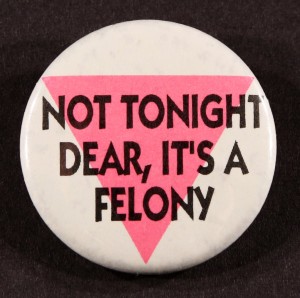

In 1993, Linda Gryczan told her neighbors she was suing the state of Montana to overturn a law that criminalized gay sex. Though she “was afraid that someone might burn down her house,” her neighbors—and activists across the state—rallied to her cause. But those who believed homosexuality should remain a crime also mobilized. Women took leading roles on both sides of the decades-long fight over Montana’s deviate sexual misconduct law.

Passed in 1973, Statute 45-5-505 of the Montana Code Annotated defined “deviate sexual relations” as “sexual contact or sexual intercourse between two persons of the same sex or any form of sexual intercourse with an animal.” Though rarely enforced, the law carried a fine of up to fifty thousand dollars, as well as ten years in prison, and made same-sex consensual intimacy a felony.

At the urging of gay and lesbian rights advocates, Montana state representative Vivian Brooke (D-Missoula) introduced bills in both 1991 and 1993 to strike the law from the books. The bill failed in both sessions. Many legislators agreed with Rep. Tom Lee, who argued that “[God] has declared homosexual activity to be wrong, and I don’t think we serve the other people of this state by contradicting him.” Others, noting that the law was not enforced, wished to avoid political fallout over what they saw as a symbolic vote.

Continue reading “We Are No Longer Criminals”: The Fight to Repeal Deviate Sexual Misconduct Laws