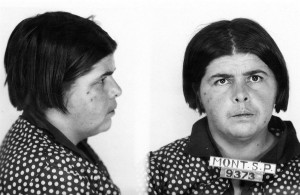

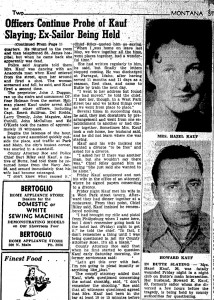

Shortly before eleven on February 8, 1946, as Hazel Kauf stepped off the Aero Club’s dance floor, she was confronted by her ex-husband, Howard Kauf, who had entered the club a few minutes earlier. Grabbing Hazel by the arm, Howard “spun her around . . . and in the spin just . . . blasted that first one [shot].”As Hazel lay on the floor, Howard, standing over her, fired a second shot into her chest. According to the Montana Standard, the horrific event quickly drew a crowd and “within a few minutes traffic at Park and Main [just outside the club] was virtually at a standstill.”

This was not an isolated incident. Following World War II, rates of violence increased nationally, and rising rates of wife assault and wife homicide, like other forms of violence, peaked in postwar Butte. Hazel’s case, however, represents more than a historically persistent crime, often addressed only in whispers. It demonstrates that even as social constraints on women lifted, cultural beliefs that dictated women’s and wives’ behaviors remained firmly intact. These beliefs perpetuated the narrative that assault on wives can, in some situations, be justified.

The lives of Hazel and Howard Kauf, in many ways, resembled the lives of couples across Montana and the United States during World War II. Philipsburg native Hazel Alda Henri married Howard Kauf, a local manganese miner, in 1936. Howard spent the early war years laboring in a strategic industry, mining. In 1945, however, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy, joining fifty-seven thousand other Montanans in the armed services. Shortly after Howard’s deployment, Hazel and the couple’s four-year-old son moved to Butte, where Hazel, like over a million other military wives nationwide, entered the workforce. Continue reading Womanhood on Trial: Examining Domestic Violence in Butte, Montana

![Catalog # PAc 96-9 3 [Montana State Vocational School for Girls.] 1920](https://montanawomenshistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/101WHM-PAc-96-9-3-300x228.jpg)