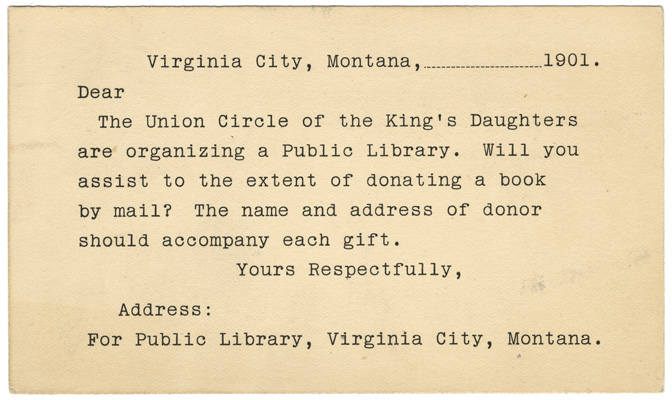

In 1952, a nun teaching sociology at the College of Great Falls committed herself to alleviating poverty among the city’s Indians. What began as an effort to solve a local problem grew into a twenty-year crusade on behalf of all American Indians, taking Sister Providencia Tolan from Great Falls to Congress. In the process, she collaborated with charitable organizations and Indian advocates to change the course of federal Indian policy.

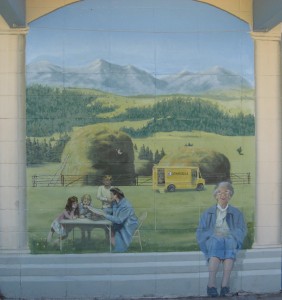

Great Falls’ Indian residents lived primarily in makeshift communities like Hill 57 on the edge of town. Their overcrowded shacks lacked utilities. Many were unskilled, undereducated seasonal laborers who struggled to provide for their families. For years, concerned citizens donated necessities to provide stopgap assistance. While supporting these efforts, Sister Providencia also approached the matter as a sociologist: studying the problem, ascertaining its root causes, and advocating social and political solutions.

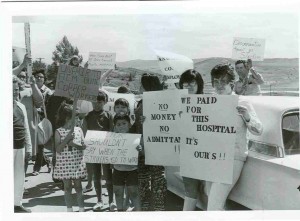

One cause of the urban Indians’ plight was the matter of jurisdiction. The federal government denied responsibility for unenrolled, non-recognized, or off-reservation Indians. City, county, and state agencies frequently refused assistance out of the misconception that all Indians were wards of the federal government.

Compounding the jurisdictional conundrum were two federal Indian policies instituted in the 1950s that increased Indian landlessness and poverty: Termination and Relocation. Under Termination, the federal government dissolved its trust responsibilities to certain tribes. Deprived of services and annuities promised them in treaties, terminated tribes liquidated their assets for immediate survival. When the Turtle Mountain Chippewa tribe was terminated in 1953, some families moved to Great Falls to live with their already impoverished relatives on Hill 57. The Relocation policy also moved Indian families to cities without ensuring that they had the means for long-term survival. Meanwhile, the government did not increase aid to states or counties so that they could cope with the expanding numbers of people in need. Continue reading Sister Providencia, Advocate for Landless Indians