In 1924, headlines across the state decried the “butchery of the helpless” at the Montana State Hospital for the Insane at Warm Springs, where eleven inmates were forcibly sterilized. Hospital staff responded that all sterilizations had received the required approval and that eugenics was “necessary to the future welfare of Montana.” Eugenics—the idea that “human perfection could be developed through selective breeding”—grew in popularity in the early twentieth century, including support for forced sterilization. The movement reached its zenith in Montana in the early 1930s, and, despite growing concerns, the practice of forced sterilizations continued into the 1970s.

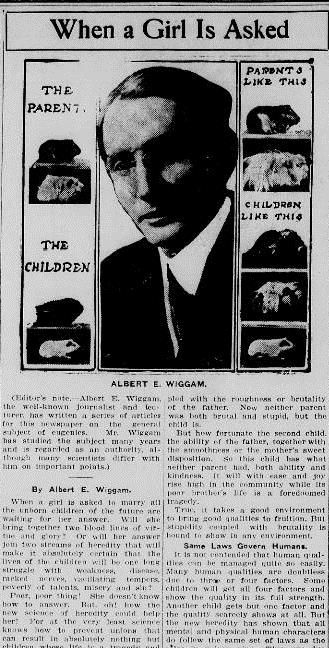

Montanans’ support for forced sterilization was part of a national trend. Eugenics proponent Albert E. Wiggam, a national lecturer and trained psychologist, helped spread the eugenics gospel in Montana through a column in the Missoulian. “Already we are taxing ourselves for asylums and hospitals and jails to take care of millions who ought never to have been born,” Wiggam wrote. Many Montanans agreed, including the Helena mother who wrote the state hospital in 1924 in support of sterilization polices. “I am a tax payer. That means I wish there was no insane, no feeble minded, and no criminals to support and to fear. . . . The very fact that these people are inmates of state institutions proves that they are morally or mentally unfit to propagate their kind.”

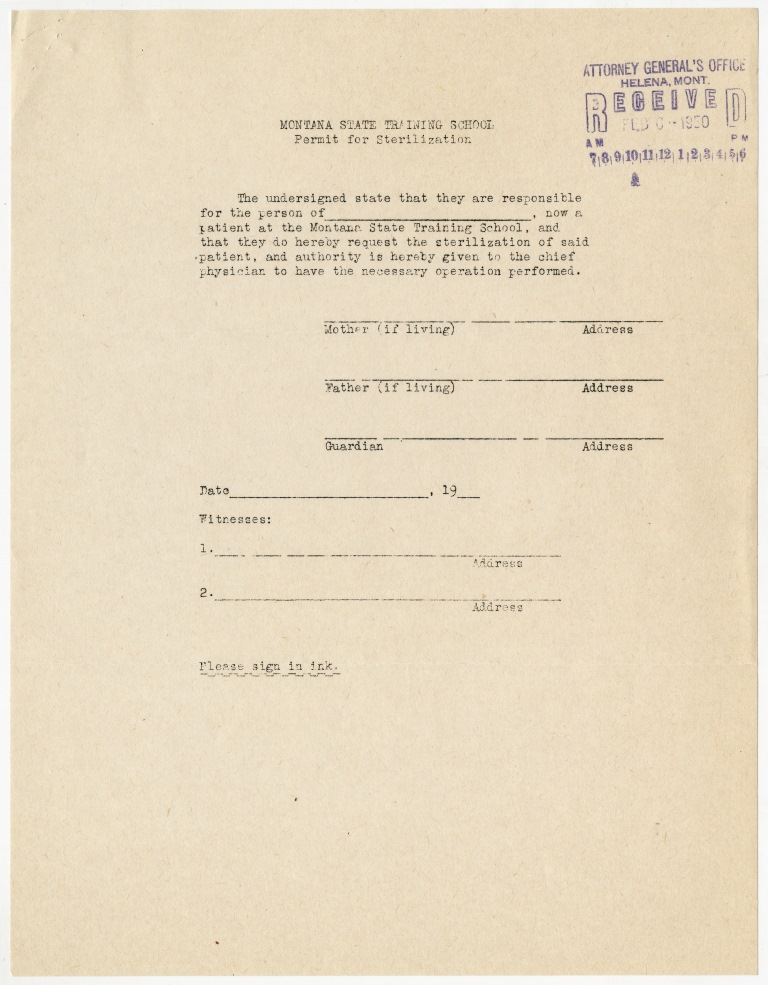

Montana institutions began sterilizing selected inmates in the 1910s, but it was not until 1923 that the state legislature created the Board of Eugenics to regulate the practice. The law establishing the board stressed that eugenic sterilization required consent—either from a legal guardian or next of kin or, barring that, from the board itself. The first board, which included several doctors, among them noted Butte physician Caroline McGill, distanced itself from eugenics’ most avid proponents by stressing that sterilization was not to be used as “a punitive measure” but for the “betterment of . . . inmate[s] or to protect society.” The board required that sterilizations be performed only at state institutions: primarily, the State Hospital for the Insane at Warm Springs and the State Training School at Boulder, both custodial establishments for those with mental disabilities.

Though in theory the law applied equally to both sexes, in application it disproportionately affected women. Of the 256 Montanans legally sterilized between 1923 and 1963, 184 (or 71 percent) were women. It also disproportionately affected the poor and the unmarried. The first three Montanans sterilized were unmarried “imbeciles” committed to the state hospital multiple times for pregnancy out of wedlock. The hospital staff suggested that, once sterilized and released, none of the women would return because they were capable of supporting themselves; sterilization prevented their readmittance and relieved the state’s burden of caring for the women’s children, all six of whom were “deficient mentally” and some of whom were already in state custodial care.

Compared with many states, Montana applied its eugenics law infrequently. Oregon sterilized over 2,600 individuals under its eugenics law, while Montana officially reported sterilizing 322. In fact, some bemoaned Montana’s low rate of forced sterilization. In 1924 the state hospital reported sterilizing twenty-three individuals but stated that “unquestionably at least four hundred-forty-seven should have been done instead.”

By passing eugenics laws, state officials gave themselves the power to control reproduction, and prejudice often influenced their decisions. In 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Buck v. Bell that forced sterilization was constitutional, infamously declaring that “three generations of imbeciles are enough.” However, the classification of “imbecile” often included women who committed petty crimes or were promiscuous. Drug addicts, the homeless, and the unemployed also found themselves targets of eugenic sterilization laws. So did members of Indian tribes.

In the 1970s, women from reservations across the United States discovered that, during the course of standard medical procedures, they had been sterilized without their consent by doctors working for the Indian Health Service (IHS). In Montana, three anonymous women from the Northern Cheyenne Reservation filed a class action lawsuit (ultimately settled out of court) alleging forced sterilization without their knowledge.

Amidst a rising outcry, Northern Cheyenne tribal judge Marie Sanchez interviewed women on the reservation and discovered that IHS doctors had sterilized at least twenty-six tribal members. Doctors told two fifteen-year-old Northern Cheyenne girls that they were having their tonsils removed; instead, the doctors removed their ovaries. Often, the IHS misled women into thinking the process was reversible or coerced their signatures by threatening to take away medical services or remove children from their homes. “The doctors that come to us are young, often fresh out of medical school,” Sanchez told a reporter, “and they want to practice on someone.”

According to a federal investigation, between 1973 and 1976, the IHS sterilized 3,406 American Indian women without their permission, intentionally targeting full-blooded Native women for the procedure. At the same time, IHS policies failed to address other health concerns on reservations, including high infant mortality rates. American Indian activists called the sterilizations genocidal. Erasing reproductive ability, many claimed, was an effort to erase the tribes themselves.

As of 2014, seven states have apologized for their role in sterilizing citizens; Montana is not among them. In 1973 the State Eugenics Board approved all twenty-four of the cases presented to it; later in the decade the board quietly dissolved. In 1987, however, the State Developmental Disabilities Planning and Advisory Council was still debating the merits of sterilization for citizens with “mental disabilities,” a debate about an issue some considered a violation of “a fundamental human right: the right to procreate.” The question of compulsory sterilization has not been conclusively resolved; although no statute remains on Montana’s law books, neither has any guarantee of reproductive rights been passed. The right to procreate in Montana remains contested. KB

Interested in the politics of reproduction? Read earlier posts to learn more about the history of abortion, birth control, and midwifery.

Sources

“Annual Report of the Board of Eugenics.” Montana State Board of Eugenics. Helena, 1972.

Chamberlain, Chelsea. “Montana State Training School Historic District National Register Nomination Form.” Draft. On file at the Montana State Historic Preservation Office, Helena, MT, 2014.

Dillingham, Brint. “Sterilization of Native Americans.” American Indian Journal 3, no. 7 (July 1977), 16-19.

Johansen, Bruce E. “Sterilization of Native American Women.” In Encyclopedia of the American Indian Movement. Ed. Bruce Johansen. Santa Barbara: Greenwood, 2013.

Josefeson, Deborah. “Oregon’s Governor Apologises for Forced Sterilisations.” British Medical Journal (December 14, 2002), 1380.

Kaelber, Lutz. “Eugenics: Compulsory Sterilization in 50 American States. Montana.” University of Vermont, Sociology Department, 2011.

Kluchin, Rebecca M. Fit to Be Tied: Sterilization and Reproductive Rights in America, 1950-1980. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2009.

Larson, Karmet. “And Then There Were None.” Christian Century, January 26, 1977, 61.

O’Sullivan, Meg Devlin. “’We Worry about Survival’’: American Indian Women, Sovereignty, and the Right to Bear and Raise Children in the 1970s.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, 2007, 64-65.

“Patients Mistreated and Mutilated by Illegal Operations at Insane Asylum While Relatives Are Forced to Pay Exorbitant Charges to Superintendent.” Helena Independent, October 5, 1924.

Paul, Julius. “Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough…” State Eugenic Sterilizations Laws in American Thought and Practice. Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, 1965. 404-407.

“People and Events: Eugenics and Birth Control.” PBS Web, October 1, 2014.

Rubin, Nilmini Gunaratne. “A Crime against Motherhood: Involuntary Sterlization Was a Horrifying Exercise in Genetic Engineering.” Los Angeles Times, May 13, 2012.

Schultz, Louisa Frank. “Sterilization for Those Involved in Mental Retardation History, Issues and Options for Montana.” Montana Developmental Disabilities Planning and Advisory Council, 1986.

__________, and Anne Moylan. “Further Consideration of the Question: Should Montana Have a Public Policy on Sterilization of Those Involved in Mental Retardation and If So, What Should It Be?” Montana Developmental Disabilities Planning and Advisory Council, 1987.

“16 Helpless Human Beings Are Said to Have Been Unsexed at Hospital.” Helena Independent, April 24, 1924.

Wiggam, Albert E. “Death Rate after Forty Increasing.” Daily Missoulian, March 30, 1914.

________. “When a Girl Is Asked.” Daily Missoulian, February 14, 1914.