Although excluded from most jobs in the mines and smelters of Butte and Anaconda (with the short-lived exception of female smelter workers in World War II), women played integral roles in the survival of these company towns. The success of each community depended on the wages of laborers who toiled for the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. When those wages were threatened—during strikes or company shutdowns—the entire community mobilized. During periods of conflict, women’s contributions to the household economy became especially significant, as women pinched pennies and took on paid employment to help their families survive. These and other activities in support of labor were crucial to community survival, but men’s resistance to women’s full participation in union efforts also reveals the prevalence of conservative gender ideals in mid-century Butte and Anaconda.

Historian Janet Finn argues that “women’s paid and unpaid labors have made a significant, if undervalued, contribution to the social fabric and economic stability of Butte.” This was especially true during strikes. Women focused on saving up money around the time that union contracts were renegotiated in case their family income was disrupted. In the event of strikes, women took jobs outside the home to supplement the family savings, stretched their household budgets as far as possible, and relied on the community for support. One woman remembered the strikes vividly: “I don’t really know how we got by. You just tried to make it day by day with coupons and strike funds and turning to your neighbors and family for help.”

Mutual female support became especially important. Another miner’s wife recalled, “It was people recognizing needs and helping one another. I know that I could go to my friends and say, ‘I’m out of this, can I have some of this.’ We traded and borrowed and handed down clothing. . . . That’s far from union work, but it’s all a part of it.”

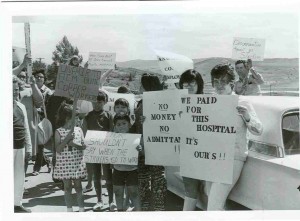

Women in Butte and Anaconda also tried to further the interests of miners by participating in local union efforts, but here they were more likely to be marginalized or excluded. Local 117 of the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (or Mine Mill) established a women’s auxiliary in 1939. The auxiliary’s goals were to educate women and children about the labor movement and assist the local union during strikes and legislative sessions.

At the national level, Mine Mill leadership placed a strong emphasis on equality, and the inclusion of women in the union was in keeping with this rhetoric. In practice, however, the activities of the Mine Mill auxiliary in Butte reflect the prevailing conservative gender ideologies. According to historian Laurie Mercier, the women of Butte and Anaconda were “excluded from the workplace and discouraged by male unionists from participating in substantive local affairs.” As a result, the auxiliary’s activities were “traditional rather than liberating.”

Mercier points to the militant masculine culture of the union as the main reason for the auxiliary’s limited success. The men of Butte and Anaconda clung to a breadwinner ideal in which the men were the single wage earner in a family and women were tethered to the world of domesticity and reproduction. Women’s attempts to become more active in union efforts—or to gain employment in the mines and smelters—were seen as an affront to this family model. According to Mercier, this ideology ultimately hamstrung the efforts of the women’s auxiliary: “[E]xcluded from the workplace and discouraged by male unionists from participating in substantive local affairs, they fell back on traditional activities of middle-class women’s groups.”

Ultimately, the Mine Mill auxiliary did not offer a comfortable home for Butte and Anaconda’s working-class women who wanted to further the interests of labor. Thus, women returned to the strategy of helping from the home and within the community. Though not always acknowledged as official contributors to union efforts, women were nonetheless crucial to community survival during times of labor unrest. Other women, at least, were able to recognize their contributions. As one daughter of a miner noted, “It’s ironic, here after all these years in the mines, my father is a trim and healthy man and it’s my mother who suffers from health problems. . . . She was the one who had to do all the worrying and make sure the family got by. If it weren’t for the women in Butte, like my mother, the men would never have survived.” AH

Interested in Butte’s women’s history? Check out “The Women’s Protective Union,” “A Compassionate Heart and a Keen Mind: The Life of Doctor Caroline McGill”, “Women…on the Level with Their White Sisters: Rose Hum Lee and Butte’s Chinese Women in the Early Twentieth Century,” and “Montana’s Whiskey Women: Female Bootleggers during Prohibition.”

Sources

Aulette, Judy, and Trudy Mills. “Something Old, Something New: Auxiliary Work in the 1983-1986 Copper Strike.” Feminist Studies 14, no. 2 (Summer 1988), 251-68.

Basso, Matthew L. Meet Joe Copper: Masculinity and Race on Montana’s World War II Home Front. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Finn, Janet L. “A Penny for Your Thoughts: Women, Strikes, and Community Survival.” In Motherlode: Legacies of Women’s Lives and Labors in Butte, Montana. Ed. Janet L. Finn and Ellen Crain. Livingston, Mont.: Clark City Press, 2006, 61-75.

Mercier, Laurie. Anaconda: Labor, Community, and Culture in Montana’s Smelter City. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

________. “Reworking Race, Class, and Gender in the Pacific Northwest.” Frontiers 22, no. 3 (2001), 61-74.

Murphy, Mary. Mining Cultures: Men, Women, and Leisure in Butte, 1914-41. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.