Rose Gordon was born 1883 in White Sulphur Springs to a former slave and a black Scottish-born immigrant. Her commitment to service makes her life notable, while the grace and advocacy she showed in navigating the racist currents common to small-town Montana sheds light on the African American experience.

Rose’s father, John, came to Montana Territory by steamboat in 1881 to cook on the mining frontier; her mother, Mary, followed a year later. The family purchased a home in White Sulphur Springs, Meagher County, where John worked as a chef for the town’s primary hotel. At the time the family settled there, Meagher County was home to some forty-six hundred people, including thirty African Americans.

In the 1890s John Gordon was killed in a train accident, leaving Mary Gordon to support five children by cooking, doing laundry, and providing nursing care for area families. Despite the long hours she gave to helping her mother, Rose graduated from high school as valedictorian. Her graduation oration, “The Progress of the Negro Race,” ended with praise for the African American educator Booker T. Washington, and Rose’s life thereafter gave testimony to Washington’s emphasis on self-improvement, self-reliance, education, and non-confrontational relationships with white people.

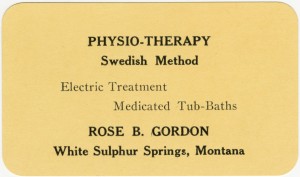

Rose Gordon aspired to be a doctor, but lacking the funds, she began nurse’s training in Helena. She soon returned home to assist her mother financially. She found employment as a domestic and as a hotel clerk in nearby Lewistown. In 1913 she tried a second time to pursue higher education, this time studying physiotherapy in Spokane, Washington, but as before, family responsibilities drew her home. Thereafter, Gordon continued to seek medical training whenever and wherever she could, though she spent most of her time making a living and assisting family members, including her brother, well-known singer Taylor Gordon, after he returned to White Sulphur Springs.

Gordon and her mother ran a restaurant and variety store in town until her mother’s death in 1924. She continued the business through the hardest years of the Depression. From 1935 through the 1940s, she also worked as a seamstress for the Works Progress Administration and owned and ran a café.

Second to medicine, Gordon’s passion was writing. In the 1930s, she began her memoir, Gone Are the Days, in which she juxtaposed descriptions of her parents’ lives and her own with lively biographical portrayals of early Montana characters. For fifteen years, she unsuccessfully sought a publisher.

From the mid-1940s until her death in 1968, Gordon nursed elderly community residents in their homes, cared for newborns and their mothers, and provided multiple physical therapy treatments each week—often coordinating her work with area physicians. She offered patients diet, exercise, and general medical and homeopathic advice and remained current in naturopathic equipment and thinking. In 1949 she received a diploma from the College of Swedish Massage in Chicago. When White Sulphur Springs acquired a bustling sawmill in the 1950s, Gordon treated workers referred and paid for by the state’s Industrial Accident Board.

Gordon also assumed the mantle of community historian, writing letters to the weekly Meagher County News on the death of many longtime residents. Each letter began, “I write to pay tribute to . . .” and in them Gordon recalled the individual’s specific contributions to the community. By 1967 the Meagher County News was regularly publishing two separate columns by Gordon: “Centennial Notes” and “Rose Gordon’s Recollections.” In them, she presented significant portions of her still-unpublished autobiography.

Gordon belonged to the Meagher County Historical Association, the Montana Historical Society, the local hospital guild, the Grace Episcopal Church, and the Montana Federation of Negro Women’s Clubs. Yet despite her active role in the community, her attempt to participate in local politics was soundly rebuffed. In 1951, she ran for mayor, ignoring an anonymous letter that threatened the resignation of all other city council members and employees should she be elected. After losing to the incumbent, 207 votes to 58, she wrote to the newspaper reminding the community that as a local business owner she was entitled to file for office and that white and “colored” soldiers were both currently dying in Korea for, among other things, better race relations.

This was not Gordon’s only public statement on race relations. On May 9, 1968, following the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Gordon wrote a letter to the Meagher County News titled “The Battle of Pigment.” In it, she acknowledged the racism she had faced in her lifetime, the debt owed to black soldiers who were “baptized into full citizenship by their bloodshed,” and her view that life was too short to focus on those who could not accept people of a different color. It was an eloquent summation of her life experience and her personal approach to racism.

Gordon died six months later. Montana Senator Mike Mansfield joined hundreds in sending Taylor, her one surviving brother, letters and cards of condolence. Community leaders served as pallbearers at her funeral. The editor of the Meagher County News wrote a poem about the woman who had paid tribute to so many others. He also gave a full page to remembrances from community members, who described Gordon’s unselfishness, compassion, wit, and curiosity; her talent for making and keeping friends; her great chicken dinners; and the courage with which she confronted racism. MSW

Learn more about notable African-American women in Montana and about women who battled discrimination.

Sources

Emmanuel Taylor Gordon Family Papers, 1882-1980. Montana Historical Society, MC 150, Helena.

“Rose Gordon” (obituary), Meagher County News, November 21, 1968, and letters of tribute published a week later, November 28, 1968.