Like their national counterparts, Montana women in the early twentieth century generally considered marriage, childbirth, and motherhood to be natural (and expected) elements of womanhood. At the same time, they did attempt to control their fertility. Conservative attitudes about sex, religious prescriptions against artificial contraception, and isolation and scarcity of medical care all conspired to limit Montana women’s access to birth control. Nevertheless, through female social networks and activism, the women of the state were able exercise a degree of control over reproduction.

Montana women had a variety of reasons for seeking contraception. Many could sympathize with the anonymous ranch wife who, when interviewed, said that she limited her family to two children “because when you had so much work to do, you can’t do all of it. So the children were the minor thing.” Other women, struggling with the hard times that hit Montana farmers and ranchers in the 1920s, sought to delay pregnancy until they were on better financial footing.

Women interested in family planning, especially those in rural areas, typically turned to other women for advice. Girls learned about sex and reproduction from their mothers or other female relatives, and homesteading women came together to discuss a range of topics related to childbearing and motherhood, including contraception. Before the widespread availability of medically sanctioned birth control devices, women used folk methods like homemade sponges, douches, and spermicides. As a last resort they would also turn to abortion, although that method was both illegal and often dangerous in the early twentieth century.

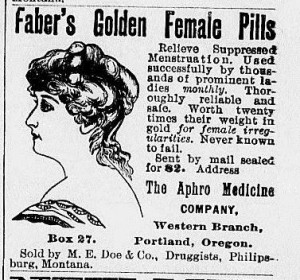

The Comstock Law of 1873 made it illegal to advertise, sell, or import contraceptive medicines and devices, and Montana law prohibited the publication or advertisement of information about contraception. Nevertheless, the national birth control movement, most famously championed by Margaret Sanger, who coined the term in 1915, slowly made its way to Montana. One Helena feminist who supported birth control was Belle Fliegelman Winestine. In the early 1920s she urged the national leaders of the League of Women Voters to take a position on the issue. For her advocacy, some of the other league members labeled her a “zealot.”

Edna Rankin McKinnon, youngest sister of Jeannette Rankin, took the matter farther, making birth control education her personal mission. A graduate of the University of Montana’s law school, McKinnon met Margaret Sanger in 1936. That same year, a federal appeals court decision ruled that the Comstock Law did not apply to contraceptive materials “which might intelligently be employed by conscientious and competent physicians.” Buoyed by this decision, McKinnon returned to Montana in 1937 to crusade for birth control education.

She encountered significant opposition. According to biographer Wilma Dykeman, “Catholic doctrine and Protestant prudery combined with traditional frontier values (masculine virility and large families . . . ) to keep birth control a taboo subject.” Moreover, Montana women “found it shocking that a lady of Edna’s background . . . would discuss diaphragms and jellies and foam powders in public meetings.” Doctors also were reluctant to help. Ultimately, McKinnon’s brother, prominent Montana lawyer Wellington Rankin, forced her to abandon her efforts in the state because he was worried that it would embarrass the family.

Nevertheless, national attitudes about sexuality had started to shift. Around 1900, writers, scholars, and feminists began to argue that “respectable” women could find fulfillment in sex (as long as it was in the confines of heterosexual marriage). This idea of “companionate marriage,” in which both husband and wife sought mutual pleasure, meant that some couples no longer perceived sex within marriage as strictly for producing children.

Family planning was an important component of companionate marriage, as birth control allowed couples to have sex without fear of pregnancy. In 1926, Margaret Sanger argued for the link between family planning and marital happiness, writing, “When the young wife is forced into maternity too soon, both [partners] are cheated out of marital adjustment and harmony that require time to mature and develop. The plunge into parenthood prematurely with all its problems and disturbances, is like the lighting of a bud before it has been given time to blossom.”

In Montana, conservative forces, including the Catholic Church, resisted this shift in attitude. According to historian Mary Murphy, Margaret Sanger was advised not to visit heavily Catholic Butte during her tour of Montana in the 1930s: “‘Butte would be futile, I’m afraid,’ wrote Belle Winestine, ‘on account of the great preponderance of citizens who are opposed even to listening to birth control propaganda, on account or religious convictions.’”

Even if Montanans were uncomfortable with public discussions about birth control, it seems that women were using it. Between 1915 and 1933, Montana’s birth rate steadily declined. The onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s brought additional economic strain to Montana, making family planning even more important. And when birth control was inaccessible or failed, women were more likely to turn to abortion. One Montana woman anonymously confessed that she had three abortions during the Great Depression because she and her husband felt it was “unethical” to have children they could not provide for economically. In fact, historians estimate that as many as one in four pregnancies were terminated during the Depression.

Despite such grim statistics, the times—and the laws—were changing. By the late

1930s, Montana’s physicians and pharmacists could sell and distribute birth control. While obscenity statutes still prohibited advertising or distributing information about contraception, patients now could, and did, request prescriptions for birth control without violating the law. – AH

You can find additional insight into the story of illegal abortions in Montana in another entry in this series, “‘You Had to Pretend It Never Happened’: Family Planning and Illegal Abortion in Montana.”

Sources

Bailey, Martha J. “‘Momma’s Got the Pill’: How Anthony Comstock and Griswold v. Connecticut Shaped US Childbearing.” The American Economic Review 100, no. 1 (March 2010), 98-129.

Dykeman, Wilma. Too Many People, Too Little Love: Edna Rankin McKinnon: Pioneer for Birth Control. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974.

Evans, Sara M. “Flappers, Freudians, and All That Jazz.” In Born for Liberty: A History of Women in America. New York: Free Press, 1989, 175-96.

Hill, Jennifer J. “Midwives in Montana: Historically Informed Political Activism.” Ph.D. diss., Montana State University, 2013.

Melcher, Mary. “‘Women’s Matters’: Birth Control, Prenatal Care, and Childbirth in Rural Montana, 1910-1940.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 41, no. 2 (Spring 1991), 47-56. Download by clicking here.

Murphy, Mary. Mining Cultures: Men, Women, and Leisure in Butte, 1914-41. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Sanger, Margaret. Happiness in Marriage. New York: Brentano’s, 1926.

“Some Legislative Aspects of the Birth-Control Problem.” Harvard Law Review 45, no. 4 (February 1932), 723-29.

Tubbs, Stephenie Ambrose. “Montana Women’s Clubs at the Turn of the Century.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 36, no. 1 (Winter 1986), 26-35. Download by clicking here.