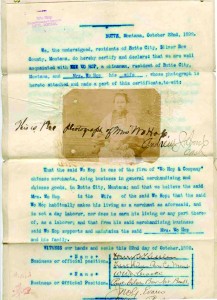

Chinese immigrants played an important role in the economic development of the West, including Montana. The 1860s mining boom and the subsequent railroad development in the region drew a diverse mix of people, including many Chinese. In spite of their role in building Montana, Chinese pioneers faced intense discrimination and their stories are often lost to history. This document is one of the few pieces of evidence we have about the life of Mrs. Wo Hop of Butte. It illustrates the precarious position of the Chinese, and especially Chinese women, in late nineteenth-century Montana.

While American businesses had welcomed—and even recruited—Chinese workers in the mid-nineteenth century, by the 1880s native-born Americans on the West Coast increasingly blamed the Chinese for unemployment and lower wages. Pressure to end economic competition, paired with the idea that the Chinese were racially inferior by nature, culminated in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The act prohibited Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States, and it was the first immigration law in American history to exclude a group based on nationality. The law allowed for the admission of certain upper-class individuals like merchants and teachers, but it was extremely difficult for these non-laborers to prove their status. Thus, until its repeal in 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act effectively ended Chinese immigration.

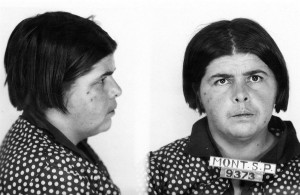

Mrs. Hop, whose husband was a merchant in Butte, carried these papers to prove that she was in America legally. As a Chinese woman, Mrs. Hop was in an especially dangerous position. The bulk of early Chinese immigrants to the United States were men, and Chinese women and families were seen as anomalies. The stereotype among native-born Americans was that Chinese women were brought to America as prostitutes, and religious and civic leaders promoted the idea that their presence posed a moral danger to American society. The Page Law of 1875 had imposed stiff penalties on the importation of Chinese prostitutes, and the enforcement of the law reflected a strong cultural assumption that women who immigrated from China were coming for illicit purposes. Continue reading Discrimination: The Case of Mrs. Wo Hop