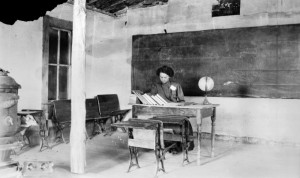

When Blanche McManus arrived to teach at a one-room schoolhouse on the south fork of the Yaak River in 1928, the school contained a table, boards painted black for a chalkboard, and a log for her to sit on. She had four students: a seventh-grade boy who quit when he turned sixteen later that year; a thirteen-year-old girl who completed the entire seventh- and eighth-grade curriculum in just four months; a sweet-natured first grader; and a lazy fifth-grade boy whose mother expected McManus to give him good grades. “I used to teach arithmetic and then go out behind the school house and cry,” McManus remembered. Like other teachers across Montana’s rural landscape in the early twentieth century, McManus relied on her own resourcefulness and creativity to succeed while facing innumerable challenges.

In the early 1900s, an aspiring teacher could obtain a two-year rural teaching certificate, provided she was a high school graduate, was unmarried, and passed competency exams in various subjects. Some high schools provided limited teacher training during the junior and senior years. Rural district trustees, some of whom had little formal education themselves, assumed students would become miners, wives, or farmers like their parents and therefore needed only a rudimentary education. They frequently hired two-year certified teachers fresh out of high school.

Nonetheless, when eighteen-year-old Loretta Jarussi applied for her first teaching position at Plainview School in Carbon County in 1917, the school board initially balked at her lack of experience. Then one board member declared they ought to hire Jarussi because she had red hair and “the best teacher I ever had was a redhead.” Jarussi got the job. Once employed, Jarussi felt she was “getting rich fast.” A female teacher in a rural school could earn sixty to eighty dollars per month at that time; a male teacher earned roughly 20 percent more.

Teaching in rural schools presented numerous challenges. Rural districts had limited budgets, and the length of a school year varied greatly, even among neighboring schools. Seldom did a teacher stay at the same school for more than two consecutive years, making it hard to track student progress. Additionally, inconsistent curricula and the high number of non-English-speaking immigrant children in Montana’s rural schools meant teachers could not count on a student’s age to determine his or her grade level. Invariably, some older students left midyear to help on homesteads, to find wage work, or because their parents felt they did not need additional education.

In addition to teaching, rural teachers cleaned and maintained their schools. Rural schools lacked indoor plumbing and were heated by woodstoves, so teachers carried water and chopped firewood. The caboose-like “little red schoolhouse” in Lincoln County, where Blanche McManus taught in the 1930s, was built on wheels so it could be moved with the logging camp. Cold air drifted through the floorboards in winter, forcing McManus and her twenty-five students to wear their coats, hats, and mittens to stay warm.

McManus believed that having empathy for students was essential to a teacher’s success. She once taught a family of students whose mother had recently died. The older siblings brought their three-year-old brother to school so that none of them would miss out on an education. Recognizing that the children had made the best of their situation, McManus quietly integrated the youngster into the classroom.

Young women teachers frequently boarded with their students’ families—an arrangement that had both advantages and drawbacks. McManus fondly remembered that two young students “called me Blanche at home and treated me as if I were a sister . . . but the minute school started, I was ‘Miss McManus!’” Loretta Jarussi, however, felt as if she were “on display all the time” when she boarded at one trustee’s home. Later that year she shared a bed with a former teacher’s elderly mother. Her next “room” was a fold-out cot that she shared with her host family’s daughter. She was relieved when she obtained a one-room cabin of her own at Huntley Butte the following year.

At work and at home, female teachers were held to gender-specific behavioral standards or risked losing their jobs. They could be fired for smoking (even at home), for having unsupervised male visitors, or for any action that generated dissatisfaction among trustees (who, very often, were students’ parents). A trustee who did not like the grades Loretta Jarussi gave his son—a mediocre student at best—refused to hire her the following year. Many teacher contracts stipulated that a female teacher who married would be fired within thirty days. During the Great Depression, when married women could teach in some districts, they were let go if their husbands were employed.

Even under the roughest conditions, Montana’s women teachers persisted in their vocation. A two-year certificate did not permit teaching at urban public schools, so ambitious rural teachers, like Loretta Jarussi and her sister, Lillian, spent several summers working toward a college degree at the State Normal College in Dillon, one of the few Montana institutions that offered teacher education. Both Jarussi sisters took better-paying positions in urban schools and taught for over forty years. Neither one married. “We needed the job!” Loretta said.

Despite biased hiring practices and innumerable challenges, many female rural teachers appreciated the autonomy of working in what one called “this little kingdom all my own.” While some women retired to start families, many others became fully certified teachers, principals, or superintendents. After several years teaching in rural schools, Blanche McManus taught high school in Sunburst and then at Western Montana College, where she trained future teachers.

Although she likened her experiences teaching in Lincoln County’s remote one-room schools to running a three-ring circus, McManus also believed it was “the most important job in the world.” LKF

“The Education of Josephine Pease Russell” tells the story of a trailblazing Crow teacher.

Learn more on the role of religious organizations in founding Montana schools in “Early Social Service Was Woman’s Work.”

Sources

Anderson, Faye. Faye Anderson interview, January 5, 1982. Interviewed by Mary Melcher. OH 229, Montanans at Work Oral History Project. Montana Historical Society Archives, Helena.

Connor, Mary Frances Benton. Mary Frances Benton Connor Papers (1921), SC 2575. Montana Historical Society Archives, Helena.

Jarussi, Loretta, and Lillian Jarussi. Lillian and Loretta Jarussi Interview, September 24, 1982. Interviewed by Laurie Mercier. OH 363, Montanans at Work Oral History Project. Montana Historical Society Archives, Helena.

McManus, Blanche. Blanche McManus Interview, September 14, 1982. Interviewed by Rex C. Myers. OH 352, Montanans at Work Oral History Project. Montana Historical Society Archives, Helena.

Swift, Amanda. Amanda Swift Writings (n.d., circa 1910-1925) and “Origins and Programs of the Schools of Winnett.” SC 821. Montana Historical Society Archives, Helena.