On November 3, 1914, Montana became the eleventh state to empower women with the right to vote. Two years later, newly enfranchised Montana women helped elect Jeannette Rankin to the U.S. House of Representatives. She took her seat as the first woman to serve in Congress four years before women achieved national suffrage. Rankin’s victory largely eclipsed another, equally significant 1916 victory: that year Montana also seated the first two women in the state’s House of Representatives. These women opened the door for those who followed in the political arena.

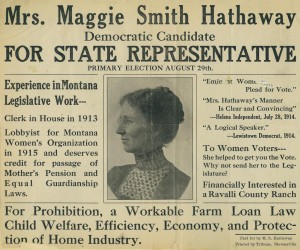

Emma Ingalls, a Republican from Flathead County, and Maggie Smith Hathaway, a Democrat from Ravalli County, represented opposing parties, but they both championed the cause of women’s suffrage and spoke out for the disenfranchised. As Ingalls and Hathaway took their seats in the Montana House in 1917, they represented the ribbon at the end of the finish line in a hard-won race. Conscious of their role as female reformers, both championed child welfare and women’s rights in the legislature.

Lifelong feminist Emma Ingalls used the newspaper she and her husband founded, the Kalispell Inter Lake, to editorialize for civic reform. A rival editor said she was a clever and interesting writer who “occasionally wielded a caustic pen.” During her first term in 1917, Ingalls introduced the national suffrage amendment when it came before the Montana House for ratification. During her second term, Ingalls sponsored a bill establishing the Mountain View Vocational School for Girls. Before that time, courts sent both boys and girls to the state reform school at Miles City. Separation of boys and girls was an important step in the care of delinquent juveniles.

After serving a second term, Ingalls was the first woman to work with the Bureau of Child and Animal Protection, chairing the northwest district under Gov. Joseph Dixon. Despite her accomplishments, Ingalls believed her life was unremarkable. “God put me on his anvil and hammered me into shape,” she once said. “The things that seemed so hard to bear at the time have proven to be the stepping stones to a larger, richer life.”

Maggie Smith Hathaway, acclaimed for translating ethics into action, also blazed a long and noteworthy trail. Hathaway traveled thousands of miles campaigning vigorously for women’s suffrage before the 1914 election. She did the same for Prohibition in 1916, speaking in every neighborhood in Ravalli County.

Hathaway’s fellow male legislators affectionately, but pointedly, called her “Mrs. Has-Her-Way” for her power of persuasion. She drafted Montana’s Mother’s Pension Bill, fought to create the Child Welfare Division, and made the speech that won the eight-hour workday for women.

With nearly 10 percent of Montana’s men serving in World War I, Hathaway recognized women’s capabilities to serve on the home front. She employed only women on her “manless” ranch so more men could join the armed services. She gathered apples as well as ballots, hitched up her own plow, and turned furrows as straight as any man. A male legislator said of the diminutive redhead, “She is the biggest man in the House.”

Emma Ingalls served two terms and Maggie Hathaway served three. Both made valuable contributions and earned the respect of, and courtesy from, their male colleagues.

There were other political firsts for Montana women. Dolly Cusker Akers was the first Native American elected to the Montana House of Representatives. Akers, active in tribal politics, was the only woman elected to the legislature in 1932. She chaired the Federal Relations Committee that handled Indian affairs. She also oversaw passage of legislation that allowed Indians to send their children to schools run by their own communities and not by the government.

A significant milestone came in 1939, when the three female Democratic state representatives–Minnie Beadle, Clare Martin, and Marian Melin–carried a bill amending the definition of “jury.” Women did not usually serve on juries because the law defined the term as “a body of men.” Changing the definition of jury to “a body of people” gave women equal responsibility to serve. And there was another milestone in 1945 when Ellenore Bridentstine was the first woman elected to the Montana Senate.

Women have prompted some of the legislature’s most memorable moments, and some were not above shenanigans when the occasion suited. The late Polly Holmes, a Democrat beloved by veteran lawmakers for her outspoken views, served during the 1970s. She sponsored the first Montana bill to ban smoking in public places. When she rose to read her bill, opponents all lit up cigars. Unfazed, Holmes put on a medical mask and wore it while she read.

Women who have served Montana have given much of themselves to the state. Emma Ingalls and Maggie Hathaway each made a name for herself by courageously acting on her convictions, and they left a legacy for other women to follow. Those mentioned here and others paved the way for today’s women who have carved a career in Montana politics. EB

To learn more about Montana women’s political activism of the late twentieth century, read Working to Give Women “Individual Dignity”: Equal Protection of the Laws under Montana’s Constitution. To learn more about how groups of women mobilized to change Montana politics, read The Power of Strong, Able Women: The League of Women Voters of Montana and Constitutional Reform.

Learn more about Montana women in politics by viewing the University of Montana’s online exhibit.

Sources

Chase, Candace. “Emma Ingalls: Trailblazing Journalist, Legislator.” Daily Inter Lake (Kalispell), April 12, 2009. Accessed November 28, 2013.

“Maggie Smith Hathaway.” 125 Newsmakers, Great Falls Tribune, 2013. Accessed November 28, 2013.

National History Museum. “Women Wielding Power, Pioneer Female State Legislators.” Accessed November 28, 2013.

North West Digital Archives (NWDA). “Dolly Smith Cusker Akers.” Accessed November 28, 2013.