“The girls range in age from jail bait to battle ax,” wrote Monroe Fry of Butte prostitutes in 1953. “[They] sit and tap on the windows. They are ready for business around the clock.” Fry named Butte one of the three “most wide-open towns” in the United States. The other two—Galveston, Texas, and Phenix City, Alabama—existed solely to serve nearby military bases, but Butte’s district depended upon hometown customers. Butte earned the designation “wide-open”—a place where vice went unchecked—largely because of its flamboyant, very public red-light district and the women who worked there.

For more than a century, these pioneers of a different ilk, highly transient and frustratingly anonymous, molded their business practices to survive changes and reforms. As elsewhere, the fines they paid fattened city coffers, and businesses depended upon their patronage. Reasons for Butte’s far-famed reputation went deeper, however, as these women filled an additional role. Miners who spent money, time, and energy on public women were less likely to organize against the powerful Anaconda Copper Mining Company. As long as the mines operated, public women served the company by deflecting men’s interest.

The architectural layers of Butte’s last remaining parlor house, the Dumas Hotel, visually illustrate a changing economy and shift in clientele from Copper Kings to miners. Today, the second floor retains the original suites where Butte’s elite spent lavish sums in the high-rolling 1890s. But the ground floor’s elegant spaces, where staged soirees preceded upstairs “business,” were later converted to cribs, one-room offices where women served their clients.

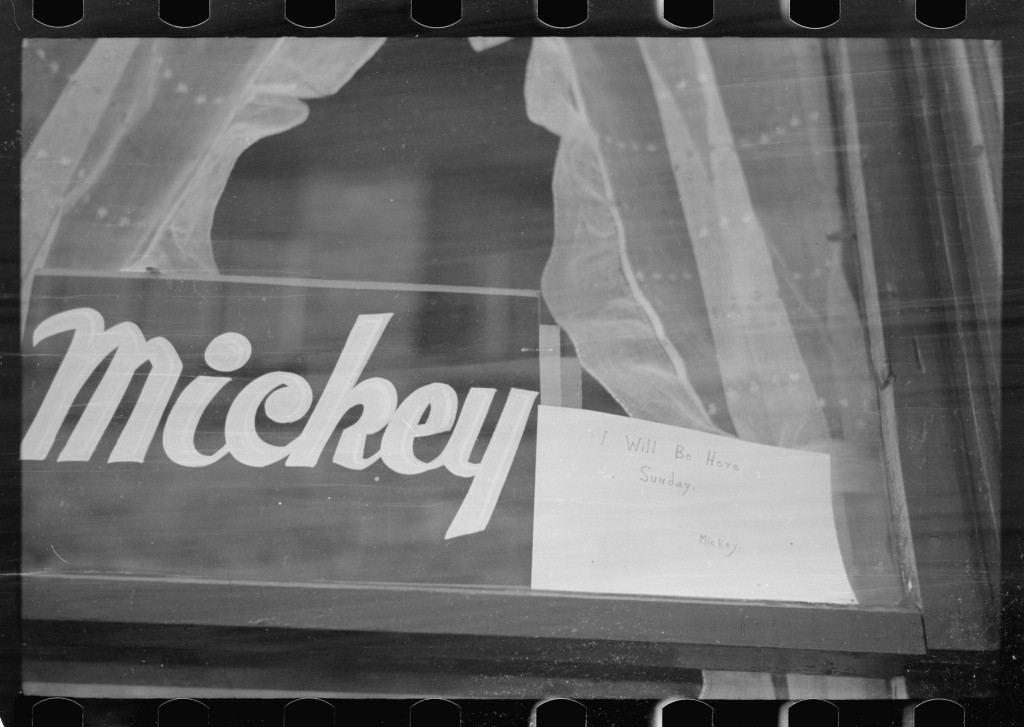

The end of the Copper Kings in 1900 signaled the end of the elegant parlor house. Anticipating changes, the women began to solicit more blatantly, lounging in the windows of houses and cribs along the district thoroughfares. Scantily clad in wrappers called “shady-go-nakeds,” they tapped on their windows, rudely addressing passersby.

In 1902, the Miner issued a special Sunday section on the red-light district that addressed solicitation, unhealthy conditions, urban blight, alcoholism, and the graft city officials openly demanded from public women. While some citizens proposed eliminating or moving the district, the Miner presented both sides of the argument. The exposé further advertised Butte’s wide-open image, luring even more miners to Butte.

Public women responded to subsequent ordinances. They willingly paid crib rents and monthly fines, but orders to lengthen their dresses, don high-necked blouses, and draw their blinds left them outraged. The women cut holes in the blinds for their faces and organized a protest. In Butte, the heart of the labor movement, prostitutes banded together just this once, loudly tapping on their windows in solidarity. Even so, the city banned solicitation from public thoroughfares, at which point the women cut doors and windows in the backs of the cribs, creating the labyrinth known as Pleasant Alley.

In January 1916, the district expanded as copper rose to a high of twenty cents a pound. At the back of the Dumas, new brick cribs opened onto Pleasant Alley. Activity, however, was short-lived. In 1917, federal law closed red-light districts in an effort to protect World War I enlistees from rampant venereal disease. Prostitution in Butte—including at the Dumas—then moved to dingy basement cribs. In 1990, demolition of the nearby Copper Block revealed tiny, dirt-floored, cave-like cribs where women worked underground under deplorable conditions.

Pleasant Alley reopened in the 1930s as Venus Alley, but federal law closed the district as a wartime measure again in 1943. After World War II, several madams worked out of antique-filled dilapidated houses. Most of the legendary cribs of Venus Alley, known to Butte’s last madams as Piss Alley, fell to the wrecking ball in 1954. At the Dumas today, orange shag carpeting, a pay phone, and red trim reflect its 1960s remodeling.

In 1968, arson closed the Windsor Hotel, which had also served as a parlor house. Its irate madam, Beverly Snodgrass, went to Washington, D.C., to complain to her senators about the loss of her business. She claimed that she had been paying seven hundred dollars monthly as protection money to Butte policemen since 1963 and that uniformed officers frequently demanded free services of her employees. Senator Mike Mansfield determined, however, that this was a local matter.

After an eight-part series on Butte vice in the Great Falls Tribune, Butte’s three remaining houses closed. Only Ruby Garrett at the Dumas reopened. Customers paid about twenty dollars for the services of her several employees, and Garrett, too, claimed she paid Butte police monthly protection money. She had already been robbed twice when a third brutal holdup in 1981 prompted unwanted publicity. Charged with federal income tax evasion, Garrett promised not to reopen and served six months in federal detention. It was no accident that the Dumas’s 1982 closure coincided with the final shutdown of Butte’s mines.

Charlie Chaplin claimed that Butte’s public women were the most beautiful, the best treated, and the luckiest. In reality, Butte’s red-light district was compelling because of the disparity between its glamourous façade and its true underbelly. Women were at the heart of this double image. Today, metal figures—the work of local high school shop students—quietly commemorate the anonymous women who worked along the brick- paved alleyways. The prostitutes’ presence also lingers in Butte’s historic, wide-open mythology. EB

You an download a tour of Butte’s red-light district from the Women’s History Matters Places page.

Want to learn more? Read Ellen Baumler’s “Devil’s Perch: Prostitution from Suite to Cellar in Butte, Montana,” published in Montana The Magazine of Western History 48, no. 3 (Autumn 1998), 4-21. You can find links to the full text of all Montana The Magazine of Western History articles relating to women’s history here.

Sources

Baumler, Ellen. “Devil’s Perch: Prostitution from Suite to Cellar in Butte, Montana.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 48, no. 3 (Autumn 1998), 4-21.

____________. “The End of the Line: Butte, Anaconda and the Landscape of Prostitution.” Drumlummon Views (Spring 2009), 283-301, at http://www.drumlummon.org/images/DV_vol3-no1_PDFs/DV_vol3-no1_Baumler.pdf.

Butte Miner, January 19, 1902.

Fry, Monroe. “The Three Most Wide-Open Towns.” Esquire 47 (June 1953), 49.

Great Falls Tribune, October 13-18, 1968.

Murphy, Mary. Mining Cultures: Men, Women, and Leisure in Butte, 1914-41. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.