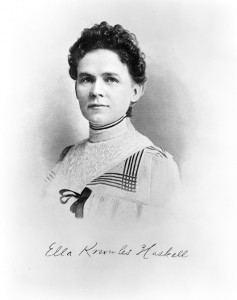

Among the formidable obstacles that prevented Ella Knowles from practicing law in Montana was the law itself. A statute prohibited women from passing the bar. However, after much debate, upon statehood in 1889 Montana lawmakers amended the statute, allowing Knowles to take the bar exam. To their amazement, she passed with ease. In fact, Wilbur Fisk Sanders, one of the three examiners, remarked that “she beat all I have ever examined.” Thus Ella Knowles became the first woman licensed to practice law in Montana and the state’s first female notary public, before going on to accomplish other “firsts.”

Ella Knowles was born in 1860 in Northwood Ridge, New Hampshire. She completed teaching courses at the Plymouth State Normal School and taught in local schools for four years. She then attended Bates College in Lewiston, Maine, which at that time was one of very few coeducational colleges in the country. Honored in oratory and composition, she graduated from Bates in 1884, one of the first women to do so.

Knowles began to read law in New Hampshire, but, under doctor’s orders, moved to Helena, Montana Territory, in 1888 to seek a healthier climate. She served as principal of Helena’s West Side School for a while but, to the dismay of her friends, gave up job security to resume legal studies under Helena attorney Joseph W. Kinsley. Through her gift of oratory, Knowles successfully lobbied the 1889 Montana territorial legislature to allow women to practice law, even though that same legislature rejected women’s suffrage.

Although some fifty women nationwide had been licensed to practice law by 1890, the idea of a woman in the legal profession was still a novelty. Passing the bar was only half the battle. Knowles also had to recruit clients if she were to practice with her mentor, Joseph Kinsley. So, like most young men starting out in the profession, Knowles solicited all the Main Street merchants, trying to convince them to hire her as a bill collector.

No one would give her a chance. One merchant, tired of her hectoring, told her to knock on the doors of several of his wealthy customers. These women had borrowed umbrellas on rainy days and not returned them as promised. Knowles managed to return all the umbrellas, but the merchant refused to pay her for her services. He feared that Knowles had offended some of his best customers. When she opened the question to other customers in the shop, they backed her up, and the merchant paid her two quarters, her first fee. She kept those quarters for the rest of her life, and the merchant himself became a steady client.

Ella Knowles was an advocate of women’s rights. Sometimes known as the “Portia of the People,” she worked tirelessly for women’s suffrage and converted many men to the cause. She was also a staunch member of the Populist Party, a third party that represented the anti-elitist views popular in the 1890s. In 1892, Knowles ran on the Populist ticket for attorney general of Montana, the second woman in the United Sates to run for that office. She covered three thousand miles in a rigorous campaign, losing the election by only a few votes—likely, in part, because women could not vote.

Henri Haskell, Knowles’s Republican opponent in the race, was so impressed with her that he appointed her assistant attorney general after he was elected. Ella and Henri were married in 1895. Now Ella Haskell, she continued to practice law. In 1896, she became the first Montana woman elected as a delegate to a national political convention, attending the Populist Party convention in St. Louis.

In 1902, when Henri decided to move to Glendive, Knowles, always sure of her own direction, chose not to follow and divorced him. Taking back her maiden name, she moved to Butte where she owned mining property and became an expert in mining litigation. She negotiated several successful mining deals and reputedly once earned a ten thousand dollar fee, the largest ever paid to a woman attorney at the time. During her career, she argued and won cases before both the U.S. Circuit Court and U.S. Supreme Court.

Ella Knowles was a woman of many Montana firsts who worked hard in a highly unusual career for a woman of her time. Although she was independent and always outspoken, she won great respect because she was also charming, feminine, eloquent, and dignified. In 1911, at age fifty, alone in her Butte apartment, Knowles died from complications of a throat infection.

In the spring of 1997, Ella Knowles was inducted into the Gallery of Outstanding Montanans in the Capitol Rotunda in Helena. Her native New Hampshire also remembers her as one of the foremost pioneer attorneys of the Northwest, a woman ahead of her time. EB

Knowles was not the only woman to get a divorce. To learn more, read “A Man in the Mountains Cannot Keep His Wife”: Divorce in Montana in the Late Nineteenth Century.

Want to learn more? Read Richard Roeder’s article, “Crossing the Gender Line: Ella L. Knowles, Montana’s First Woman Lawyer,” published in Montana The Magazine of Western History 32, no. 3 (Summer 1982): 64-75. You can find links to the full text of all Montana The Magazine of Western History articles relating to women’s history here.

Sources

Baumler, Ellen. Montana Moments: History on the Go, Helena: Montana Historical Society, 2010.

Ella Knowles Haskell. Accessed November 4, 2013.

“Ella Louise Haskell: Pioneer Woman Attorney.” Accessed November 4, 2013.

Roeder, Richard B. “Crossing the Gender Line: Ella L. Knowles, Montana’s First Woman Lawyer,” Montana The Magazine of Western History 32, no. 3 (Summer 1982): 64-75. Accessed November 4, 2013.

One thought on “Ella Knowles: Portia of the People”