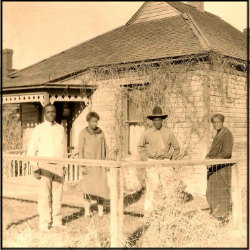

Mamie Anderson Bridgewater and her daughter, Octavia, were strong African American women who lived under the veil of racism in Helena during the first half of the twentieth century. Each earned the respect of the Helena community, and each helped to make a difference in the lives of other African Americans.

Mamie was born at Gallatin, Tennessee, in September 1872, one of eight children. In 1892, she married a career “buffalo soldier,” Samuel Bridgewater, at Fort Huachuca, Arizona Territory. In 1903 she followed her husband to Fort Harrison, Montana, where he was stationed after the Spanish-American War. There she raised five children and worked as a matron at the veterans hospital. All the while, she cared for Samuel during his frequent bouts of illness from wounds received at the Battle of San Juan Hill in 1898.

After her husband’s death in 1912, Mamie Bridgewater worked as a domestic in private homes, always scraping together enough to care for her children and grandchildren whenever they needed her assistance. She was a leader of Helena’s black Baptist congregation and was heavily involved in fund-raising for Helena’s Second Baptist Church, completed circa 1914. She was also a founder of the local Pleasant Hour Club, which organized in 1916 and became the Helena chapter of the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. At her death in 1950 at age seventy-seven, she was serving as chaplain of the Pleasant Hour Club.

Throughout her adult life, Mamie Bridgewater instilled pride in her children, and her home was always open to family and friends. She was a bulwark in times of trouble, including a son’s severe mental illness and a grandson’s tragic drowning. She also prepared her daughter, Octavia, for the work that she was to accomplish.

Octavia Bridgewater was, without doubt, a product of her mother’s encouragement. She graduated from Helena High School in 1925 and attended the Lincoln School of Nursing in New York City, which was, at the time, one of only two nursing schools exclusively for African Americans. After graduating in August 1930, she attended the University of the State of New York, where, a month later, she received her registered nurse’s degree. Returning home to Helena, Octavia discovered that Montana hospitals did not hire African American nurses, and so she worked as a private-duty nurse.

In 1941, the Army Nurse Corps began accepting a small number of African American nurses, and a year later, Octavia was one of fifty-six black nurses accepted for service. This small quota was long in coming, for African American nurses had served throughout all wars, though only as contract nurses rather than as members of the military. At the end of World War I, during the influenza epidemic when there was a severe shortage of nurses, the Army Nurse Corps enlisted eighteen black women. They cared for German prisoners of war and African American soldiers stateside, but they had never served in wartime before 1941.

During World War II, African American nurses slowly began to pierce the barriers within the military system. When Octavia joined the army in 1942, there were eight thousand black nurses in the United States. These women realized that if they were not allowed to serve in the military, black nurses would never be integrated into the mainstream medical community. Nationally, through the black press, the women mobilized for their cause. They flooded the White House and Congress with telegrams and letters. The army and navy lifted the ban against black nurses in 1945. Octavia Bridgewater’s voice was one of those that helped bring about the change.

Bridgewater not only fought for the rights of African American nurses, but her service helped improve the status of all nurses. World War II brought a new respect for women nurses, allowing them full status as officers, full employment, and an improved public image. Bridgewater herself earned the rank of first lieutenant, proud to have achieved the rank and to have supported important progress. Her role in the national movement was a life-altering experience.

When Lieutenant Bridgewater returned to Helena in 1945, she found that racial barriers had softened but had not disappeared. When the veterans hospital refused her medical treatment because she was black and a woman, she asked her congressman to intervene and he did so.

After the war, St. Peter’s Hospital in Helena began to hire black personnel, and Bridgewater served as a much beloved and long-remembered registered nurse in the maternity department until she retired in the 1960s. Like her mother, Octavia was active in both the city’s Baptist church and in the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, serving as treasurer in 1971. She died at age eighty-two in 1985.

Both Mamie and Octavia Bridgewater lived productive lives through times of great change. Both faced economic, social, and legal barriers, and both worked to overcome them and to improve their communities. Mamie did so through her club and church work and as a supportive mother. Octavia did so through civil rights organizing, club work, and her career as a nurse. Both women made important contributions to Montana’s African American community— and to the greater Helena community in which they made their home. EB

The Bridgewaters were active in the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. Read more about the organization in “Lifting As We Climb: The Activism of the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. “

Sources

Baumler, Ellen. “Haight-Bridgewater House” National Register nomination. 2014. State Historic Preservation Office, Helena, Mont.

————–. Montana Moments at http://ellenbaumler.blogspot.com/2013/02/octavia-bridgewater.html.

Munger, Mary. “Special Women of World War II.” Undated, unpublished article in “Octavia Bridgewater,” Vertical File, Montana Historical Society’s Research Center, Helena.

U. S. Army Medical Department, Office of Medical History. “African American Nurse Corps Officers” at http://history.amedd.army.mil/ANCWebsite/articles/blackhistory.html. Accessed October 27, 2013.

Another excellent story of an important Helena family!