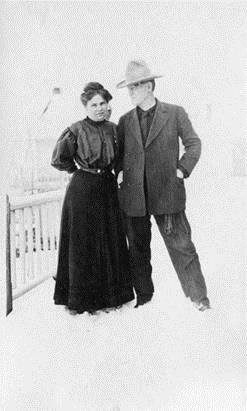

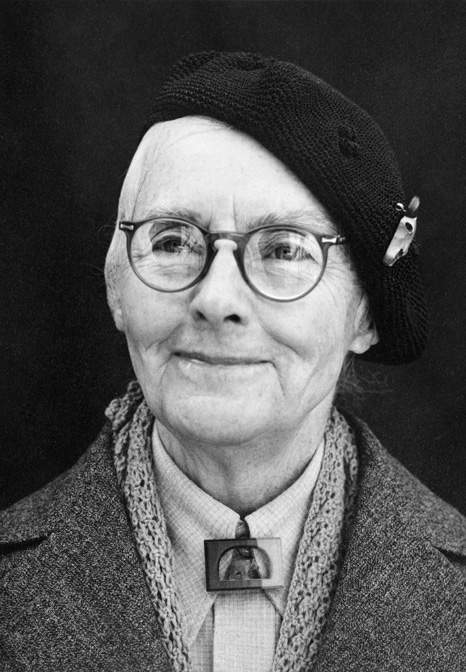

Born on a farm near Mansfield, Ohio, in 1879, Caroline McGill devoted her life to the people of Montana, her adopted state. In her work as a physician she earned the love and respect of the people of Butte, but her role in the creation of the Museum of the Rockies is her enduring legacy to all Montanans.

McGill’s family moved to Missouri when she was five, and at the age of seventeen she acquired a teaching certificate so she could support herself and complete high school. She achieved that goal in 1901 and continued her education at the University of Missouri. By 1908 she had a B.A. in science, an M.A. in zoology, and a Ph.D. in anatomy and physiology, thereby becoming the first woman to receive a doctorate from that school. She taught at her alma mater until 1911, and former students later “aver[ed] that she was the finest medical school instructor” they had had.

Although the University of Missouri offered McGill a full professorship, she decided to shift career paths and accepted a position as pathologist at Murray Hospital in Butte. In a letter to a family member, she explained her decision to move to Montana: “I’ll tell you right now I am making the biggest fool mistake to go . . . but I’m going.” “Feels sort of funny to stand off and serenely watch myself commit suicide, [but] I’ll just have to let her rip.” Continue reading A “Compassionate Heart” and “Keen Mind”: The Life of Doctor Caroline McGill