Born in Butte in 1904, Rose Hum Lee earned a B.S. in social work from Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute of Technology and completed a doctorate in sociology at the University of Chicago. Her dissertation—The Growth and Decline of Rocky Mountain Chinatowns—was published in 1978. Because her work was largely based on the experiences of her own family and childhood, her scholarship offers invaluable insights into the lives of Chinese women and families in Butte during the first four decades of the twentieth century.

The daughter of merchant Hum Wah Long and his wife, Lin Fong, Rose Hum Lee, like other Butte-born Chinese American children, attended Butte’s grammar and high schools, where she distinguished herself academically. Additionally, the fact that her father was one of the city’s most prominent Chinese businessmen conferred a level of respect on the Hum family.

Nevertheless, Lee, like other Chinese women of Butte, encountered the common racist assumption that equated Chinese women with prostitution. The Montana Standard reflected that stereotype while defending the wives of Butte’s merchants in a 1942 article about the city’s Chinese history. “While the Chinese men of Butte were, as a rule, good law-abiding citizens . . . the less said about the Chinese women of that day the better,” the Standard noted. “The exception among the women were the wives of Chinese doctors and merchants, women who were on the level with their white sisters and who have left many estimable children.” Certainly, those estimable children—like Lee—contended with pressure to maintain their respectability.

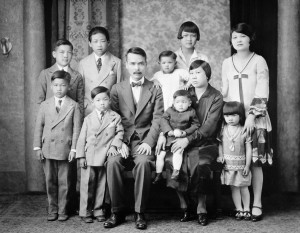

Lee herself came from a family of seven, and her research noted that the families of Butte’s first-generation Chinese tended to be large, with an average of five children. Lee found no childless couples in her study. The premium placed on family size was due in part to the fact that immigrants “brought with them village mores, [and] regarded large families as a symbol of status.” Families and extended kinship groups helped create social stability in the face of frontier life, and births were celebrated both in Butte and by extended families back in China.

According to Lee, the first-generation Chinese women who lived in Butte in the early twentieth century generally came to Montana directly from China or from other Chinese communities in the West. Many were part of arranged marriages, and in some cases they did not even meet their husbands before traveling to America. One bride remembered that her aunt had arranged for her to marry a Butte merchant who was “too busy taking care of [his business] to leave and find himself a wife.” The marriage ceremony was held in the groom’s absence, and when the young woman arrived by boat in America, her escort (a new cousin) “pointed to a figure . . . [and] said, ‘See that man smoking a big cigar? He is your husband!’”

Prior to the Chinese Revolution of 1911, married women’s lives, even in America, were carefully supervised and restricted. One Butte woman recalled, “Until the Revolution, I was allowed out of the house but once a year. That was during New Year’s when families exchanged New Year calls and feasts. . . . The father of my children hired a closed carriage to take me and the children calling . . . even if we went around the corner, for no family women walked.” The isolation and limited contact with other women made life in Butte particularly difficult, but after 1911 attitudes about women venturing into the public sphere slowly shifted: “When the father of my children cut his queue he adopted new habits; I discarded my Chinese clothes and began to wear American clothes,” one of Lee’s sources said. “Gradually the other women followed my example. We began to go out more frequently and since then I go out all the time.”

According to Lee, only three Chinese families remained in Butte by 1945. Drawn away in search of economic opportunities during the Depression and World War II, Montana’s Chinese population dwindled. Lee was among those who left. She finished her doctorate in 1947 and distinguished herself in 1956 at Chicago’s Roosevelt University by becoming the first woman, and the first Chinese American, to head a sociology department in America. Though she never again lived in her home state, her dissertation continues to be one of the most important resources on the Chinese in Montana. AH

You can find additional insight into the lives of Chinese women in Butte in another entry in this series, “Discrimination: The Case of Mrs. Wo Hop.”

Sources

Lee, Rose Hum. The Growth and Decline of Chinese Communities in the Rocky Mountain Region. New York: Arno Press, 1978.

___________. “Occupational Invasion, Succession, and Accommodation of the Chinese of Butte, Montana.” American Journal of Sociology 55, no. 1 (July 1949), 50-58.

Merriam, H. G. “Ethnic Settlement of Montana.” Pacific Historical Review 12, no. 2 (June 1943), 157-68.

O’Malley, M. G. “Echoes from the Distant Past.” Montana Standard, February 15, 1942, n.p. Copy in Chinn Family Papers, Acc. 89-30, box 2, fldr Scrapbook, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Yu, Henry. “Rose Hum Lee.” Excerpted from Thinking Orientals: A History of Knowledge Created about and by Asian Americans. New York: Oxford, 2000. http://www.maiwah.org/rhlee.shtml. Accessed January 8, 2014.

Wunder, John R. “The Chinese and the Courts in the Pacific Northwest: Justice Denied?” Pacific Historical Review 53, no. 2 (May 1983), 191-211.