One of the challenges of women’s history is that women have left behind fewer written records than men. This imbalance makes women-made folk art particularly valuable as historical evidence. As folklorist Henry Glassie elegantly put it: “Few people write. Everyone makes things. An exceptional minority has created the written record. The landscape is the product of the divine average.” Painstakingly created and lovingly used, quilts especially can help us better understand the lives of ordinary Montana women.

While often created for utility, quilts allowed women to express themselves artistically, and studying quilts allows scholars to trace changes in technology, aesthetics, and cultural values over time. Quilts can also provide greater understanding about important events in women’s lives, such as births, marriages, deaths, and travels. Montana historian Mary Murphy states that quilts are “fragments, clues, tiny jeweled windows onto the experiences of women in our past. They hint at networks of kinship and friendship, of the disruption and promise of migration, of the love of things warm and beautiful.”

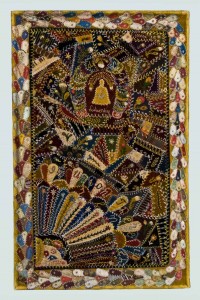

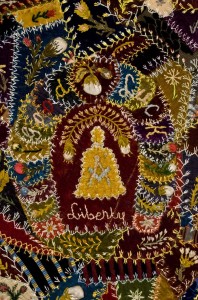

Minnie Fligelman’s crazy quilt is one example of how a quilt can offer insights into both local history and national trends. According to her daughters, Frieda Fligelman and Belle Fligelman Winestine, who donated this quilt to the Montana Historical Society in 1949, Minnie Fligelman used samples from her husband Herman’s merchandise cart to make this crazy quilt. Minnie Weinzweig and Herman Fligelman, both Romanian Jews, married in Minnesota in 1888 or 1889. In 1889 they moved to Helena, where Herman ran the New York Dry Goods Company. Because Minnie died while giving birth to Belle in 1891, this quilt must have been an important memento of a woman the girls never got to know.

Herman Fligelman was a prominent Helena merchant, who sold “honest goods for honest prices.” Lovingly preserved by her daughters, Minnie’s quilt gives us a peek at the velvets and silks that Herman’s store carried. That such lush fabrics were popular in Helena reflects the town’s mineral wealth—and the buying power of the Fligelmans’ customers.

Minnie Fligelman’s choice of quilt patterns also reveals larger historical trends. Pieced and appliquéd block quilts were the norm around the time of the Civil War, but in the 1870s American quilters suddenly broke away from the dictates of block symmetry. So-called crazy quilts became ubiquitous in the Victorian era. These quilts were usually made of silks, satins, and velvets, and characterized by elaborate embroidery and adornment. Many quilt historians trace their popularity to the 1876 International Exhibition in Philadelphia. The Japanese pavilion at the exhibition drew massive crowds and sparked an American fascination with asymmetrical art. Often used as decorative throws rather than bedding, these frenetic-looking quilts were in fact carefully planned and executed and painstakingly embroidered to display the maker’s fine needlework.

Quilt historians have offered several different interpretations of the crazy quilt trend. Some see crazy quilts as representing the abundance and excess of the Gilded Age. Ethel Ewert Abrahams and Rachel K. Pannabecker argue that the quilts “exemplified both the maker’s access to luxury fabrics and the leisure time to ornament her home.” On the other hand, unlike block quilts that required large supplies of fabric, asymmetrical crazy quilts were not just luxury items for members of the upper class. “Because of its scrappy structure,” Abrahams and Pannabecker continue, “a crazy quilt was within the reach of any woman with access to scraps of fabric and the determination to make her own fashionable quilt.”

Women might also have chosen crazy quilts as a quiet form of rebellion. Sue Barker McCarter argues that women embraced the asymmetrical chaos of the crazy quilt as a way to push back against the strict Victorian mores of the time, and Frances Lichten suggests that crazy quilts were “restless textiles” and “protests against the shackles of needlework discipline.”

Regardless of women’s motives for embracing the pattern, crazy quilts are significant as one of the first “national” quilt patterns. Disseminated by popular magazines of the time such as Godey’s Lady’s Book, crazy quilts represent the increasing connectedness within America at the end of the nineteenth century. This is perhaps why so many crazy quilts like Minnie Fligelman’s were found in Montana at the turn of the century—they represented one way for Montana women to demonstrate that they could be as fashionable as their eastern sisters. – AH

Learn more by reading Annie Hanshew’s book, Border to Border: Quilts and Quiltmakers of Montana (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2009) or Mary Murphy’s article, “Montana Quilts and Quiltmakers: A History of Work and Beauty” in Montana The Magazine of Western History 58, no. 3 (Autumn 2008), 23-25, 33-47, 94-95.

Sources

Abrahams, Ethel Ewert, and Rachel K. Pannabecker. “‘Better Choose Me’: Addictions to Tobacco, Collecting, and Quilting, 1880-1920.” Uncoverings, 2000.

Berlo, Janet Catherine, and Patricia Cox Crews. Wild by Design: Two Hundred Years of Innovation and Artistry in American Quilts. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003.

Glassie, Henry. “Meaningful Things and Appropriate Myths: The Artifact’s Place in American Studies.” In Material Life in America, 1600–1860. Edited by Robert Blair St. George. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1998.

Hanshew, Annie. Border to Border: Historic Quilts and Quiltmakers of Montana. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2009.

______. “From Sunburst to Nine-Patch: Treasures of the Nineteenth Century.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 58, no. 3 (Autumn 2008), 25-32, 94.

Hedges, Elaine. Hearts and Hands: Women, Quilts, and American Society. Nashville: Rutledge Hill Press, 1987, repr. 1996.

________. “Quilts and Women’s Culture.” The Radical Teacher, no. 4 (March 1977), 7-10.

Hornback, Nancy. Kansas Quilts and Quilters. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1993.

Kenney, Alice P. “Women, History, and the Museum.” The History Teacher 7, no. 4 (August 1974), 511-23.

McCarter, Sue Barker. “Crazy Quilts: Quiet Protest.” In Ruth Haislip Roberson, ed., North Carolina Quilts. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

Murphy, Mary. Montana The Magazine of Western History 58, no. 3 (Autumn 2008), 23-25, 33-47, 94-95.

Phillips, Brenda. “Women’s Studies in the Core Curriculum: Using Women’s Textile Work to Teach Women’s Studies and Feminist Theory.” Feminist Teacher 9, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 1995, 89-92.

Woodward Thomas K., and Blanche Greenstein. Twentieth Century Quilts, 1900-1950. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1988.

I treasure the book “Border to Border: Quilts and Quiltmakers of Montana (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2009)” and highly recommend it to all the western quilters I know! Great stories and beautiful pictures!