On November 3, 1914, Montana men went to the polls, where they voted 53 to 47 percent in favor of women’s suffrage. Along with Nevada, which also passed a suffrage amendment that year, Montana joined nine other western states in extending voting rights to non-Native women. (Indian women would have to wait until passage of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act to gain the ballot.) Montana suffrage supporters rejoiced, and in 1916 followed up their victory by electing Maggie Smith Hathaway (D) and Emma Ingalls (R) to the state legislature and Jeannette Rankin (R) to the U.S. Congress. In this seeming wave of feminism, May Trumper (R) also became the state superintendent of public instruction.

An air of inevitability surrounded the victory but it had not come easily. Montana women’s rights advocates first proposed equal suffrage twenty-five years earlier at the 1889 state constitutional convention. Fergus County delegate Perry McAdow (R), husband of successful businesswoman and feminist Clara McAdow, championed the cause. He even recruited long-time Massachusetts suffrage proponent Henry Blackwell to address the convention.

Blackwell was an articulate orator, but he did not have the backing of a well-organized, grassroots movement. “There has never been a woman suffrage meeting held in Montana,” he lamented. Nevertheless, Blackwell hoped to convince the delegates to include constitutional language allowing the legislature to grant equal suffrage through a simple majority vote instead of requiring a constitutional amendment. That proposal failed on a tie ballot.

Although the constitutional convention did not grant them equal suffrage, Montana women did retain the right to vote in school elections (first ceded to them by the 1887 territorial legislature). The new constitution also granted all tax-paying women the right to vote on questions concerning taxpayers. For Montana feminists, however, the goal was equality in voting rights. It proved a difficult target. Suffrage clubs formed and disbanded as the movement lurched between periods of concentrated effort and years of “discouragement and apathy.” The state legislature voted on equal suffrage during almost every session between 1895 and 1911. Suffrage questions sometimes passed in the House, but never by the required two-thirds—and never in the Senate. Without the two-thirds majority in both houses, the question could not be put to a simple vote of the people.

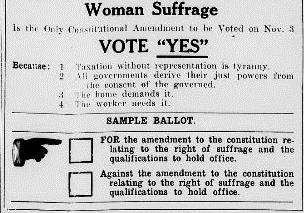

After the 1911 session, however, a sophisticated and multifaceted organizing campaign changed the momentum. The first step toward victory came when suffrage advocates convinced both the Democratic and Republican parties to write equal suffrage into their platforms. Then, in January 1913, the legislature passed a women’s suffrage bill by large majorities (26 to 2 in the Senate and 74 to 2 in the House). This left the 1914 popular vote as the last hurdle to amending the state constitution.

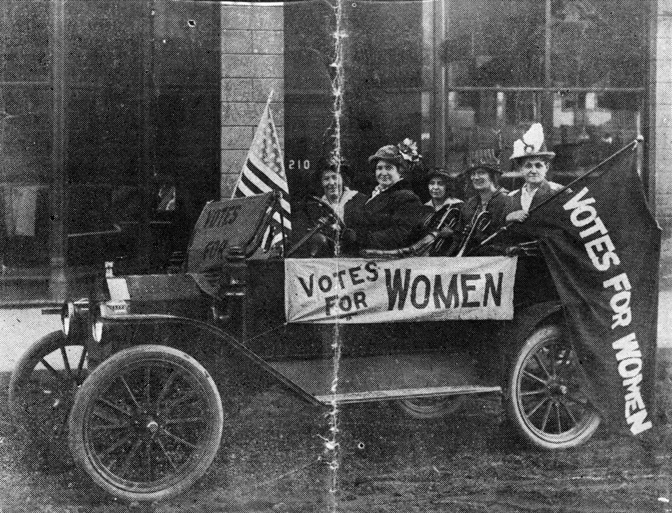

Jeannette Rankin is undoubtedly Montana’ most famous suffragist, but the movement’s final triumph involved hundreds of women across the state. Belle Fligelman, of Helena, shocked her mother by speaking on street corners and in front of saloons. Margaret Smith Hathaway, of Stevensville, traveled over fifty-seven hundred miles promoting the cause and earning the nickname “the whirlwind.” The Missoula Teachers’ Suffrage Committee published and distributed thirty thousand copies of their leaflet, “Women Teachers of Montana Should Have the Vote.”

The campaign found arguments for every interest group, bringing in outside talent as necessary. New York laundry worker Margaret Hinchey proved particularly popular. The plainspoken Irish immigrant undoubtedly converted at least some of Montana’s class-conscious miners and loggers with her fiery speeches advocating equal suffrage as a tool for advancing the cause of workingwomen.

From its headquarters in Butte, the Montana Equal Suffrage Association (MESA) “mailed letters to women’s clubs, labor unions, granges, and other farm organizations, asking for pro-suffrage resolutions.” During the state fair, MESA published a daily paper, underlining its dual argument for suffrage. The first was simple justice: “those who must obey the laws should have a voice in making them.” The second asserted that women’s ingrained morality would reduce political corruption and make it easier to pass humane legislation.

Women voters as a moral force was the prime argument of the state’s oldest suffrage organization, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). The WCTU had over fifteen hundred members and fifty chapters in Montana and ran its own campaign. State president Mary Alderson Long, of Bozeman, traveled forty-five hundred miles and effectively mobilized her members to engage in neighbor-to-neighbor campaigns. Nevertheless, MESA did not allow WCTU members a float in its grand suffrage parade for fear of tarring the suffrage movement with the temperance brush.

The campaign emerged victorious despite such disagreements on tactics and the inevitable interpersonal rivalries. Ravalli County voted 70 percent in favor of equal voting rights, Missoula County 64 percent, and Yellowstone County 57 percent. The suffragists squeaked out a narrow victory in Hill County, but lost Silver Bow (home to Butte) by a mere thirty-four votes. In general, farming counties supported suffrage, while mining counties opposed it—possibly out of fear that women would vote in Prohibition.

With the passage of equal suffrage, women had won the battle for justice. The promise that they would make politics more moral remained an open question. As the Harlem Enterprise editorialized after the votes were counted: “Evidently Montana has a better educated body of men who recognize the intelligence of their women. . . . Now we will see whether politics in the state will be more ‘rotten’ than under the control of men.” MK

Want to learn more about the suffrage campaign? Visit our Suffrage page.

Montana women used the momentum of their success to expand their influence into new areas of influence. Read “After Suffrage: Women Politicians at the Montana Capitol” to learn more.

Sources

Alderson, Mary Long, Papers, 1894-1936. Montana Historical Society Archives, SC 122

Cole, Judith K. “A Wide Field for Usefulness: Women’s Civil Status and the Evolution of Women’s Suffrage on the Montana Frontier, 1864-1914.” American Journal of Legal History 34, no. 3 (July 1990), 262-92

Harlem Enterprise, November 19, 1914. Accessed December 16, 2013

Larson, T. A. “Montana Women and the Battle for the Ballot.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 23, no. 1 (Winter 1973), 24-41. Accessed December 16, 2013

Petrik, Paula. No Step Backward: Women and Family on the Rocky Mining Frontier, Helena, Montana, 1865-1900. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 1987

Schaffer, Ronald. “The Montana Woman Suffrage Campaign: 1911-14.” Pacific Northwest Quarterly 55, no. 1 (January 1964), 9-15

Smith, Norma. Jeannette Rankin, America’s Conscience. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2002

Suffrage Daily News (Helena and Butte), September 24-26, 1914, and November 2, 1914. Accessed December 17, 2013.

Ward, Doris Buck. “The Winning of Woman Suffrage in Montana.” M.A. thesis, Montana State University, 1974

Wheeler, Leslie A. “Woman Suffrage’s Gray-Bearded Champion Comes to Montana, 1889.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 31, no. 3 (Summer 1981), 2-13. Accessed December 16, 2013

Winestine, Belle Fligelman. “Mother Was Shocked.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 24, no. 3 (Summer 1974), 70-79. Accessed December 17, 2013

0 thoughts on “The Long Campaign: The Fight for Women’s Suffrage”