In 1937, Josephine Pease became one of the first Crow (Apsáalooke) people to graduate from college. Cultural and linguistic differences made obtaining an education challenging, but even greater were the difficulties that came with being a Crow woman who wanted a career in the mid-twentieth century. Crows discouraged women from being more successful than men, while some whites refused to hire Indians. Nevertheless, Pease persisted in her dreams to become a teacher, blazing a trail for future generations of Crow women.

The oldest of five children, Josephine was born in 1914 and grew up near Lodge Grass. Her parents wanted her to go to school because neither of them had had a chance at an education. There was a missionary school in Lodge Grass, but Josephine’s parents wanted her at the public school. For two years Josephine was the only Crow child at the school. The rest were “English” (white) children who wouldn’t play with her. She remembered feeling as if she were “in a foreign country.”

Many local white residents did not want Crow children attending the public schools on the reservation because tribal members did not pay property taxes. Then, in 1920, Congress passed the Crow Act, which specified the tribe’s land grants for schools and opened Montana’s public schools to Crow students.

For Apsáalooke children, going to school presented many challenges. While the girls kept to themselves, the Crow and “English” boys fought with each other. In Apsáalooke culture, girls and boys played separately from one another, but at school their teachers taught them games that included all of the children. In the classroom, the Crow students, who had been raised to be very modest, found it hard to “put themselves forward” as their teachers expected them to.

The Crow students’ greatest difficulty, however, was language. Josephine’s friend, Joe Medicine Crow, started school in 1924 and was still in first grade five years later because he found it so hard to learn English. “We were there to get an education, to learn to speak English, so we were discouraged from speaking Crow,” Pease recalled. It would have made their education easier, she thought, if the teachers had been bilingual, as was her high school English teacher, Genevieve Fitzgerald.

The daughter of Baptist missionary Dr. W. A. Pedzoldt, Genevieve Pedzoldt Fitzgerald had grown up in Lodge Grass, where she learned Crow. Her willingness to explain ideas in their language enabled Crow students to gain fluency in English and thus improve in all subjects.

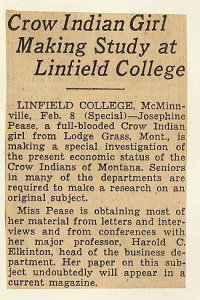

Pease credited her teachers for giving her “a push forward to become educated.” Both Mrs. Fitzgerald and Mrs. Stevens, her science teacher, encouraged her to attend college. Her mother also advised her to get a college degree and a good-paying job. “I want you to go into this world and have a place somewhere that you can call your own where you will be making money,” she told Josephine. With help from Dr. Pedzoldt, Josephine applied to Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon. Pedzoldt and the Baptists paid her tuition.

For the first two weeks at Linfield, Josephine was so homesick that her father sent her a return ticket, but the college president and his wife convinced her to stay another week. Then she met two girls from China. Realizing how far they had come for a college education, Josephine decided to stay.

Josephine Pease graduated in 1937 with a major in business and a minor in English. One of the first three Crow college graduates (all of whom were women), she returned to the reservation, hoping to find a job as a high school business teacher. She soon became frustrated with the lack of employment opportunities for educated Crows, who were overlooked in favor of whites for jobs on the reservation. The fact that she was a woman also seemed to count against her. During the next three years she worked at menial office jobs, married briefly, and had a daughter.

Eventually, Pease secured a teaching post at a small country school at Soap Creek. Her mother came to live with her and cooked for her eight students. Pease said her two years at Soap Creek were a “hard life” of poverty.

In 1942, opportunities opened up at Crow Agency School as teachers left for the war. For the next seventeen years, Pease taught young students who did not speak English. She then spent two years in the Teacher Corps, training teachers to work with Native students.

After two decades of teaching, Pease became director of the Head Start program on the reservation. As a Crow woman in a leadership position, Pease faced discrimination and prejudice from both the white and Crow communities. Non-Indians resented having an Indian person in charge, while many Crows, particularly men, did not want a Crow woman to achieve something beyond what they themselves had achieved. Reluctantly, Pease retired after two years. “Our own people can get really tough . . . It was really difficult,” she recalled. Even in the late 1980s, Pease observed that Crow women were still expected to do less than they were capable of so as not to surpass the men.

Josephine Pease Russell showed that Crow women could achieve an education, support themselves, and rise to leadership positions. She set the stage for the next generation, when her niece, Janine Pease—the first Crow to earn a doctoral degree—became the founding president of Little Big Horn College. LKF

Sources

Medicine Crow, Joe. Interviewed by Bill LaForge, January 30, 1989. Oral History 1226, Montana Historical Society, Helena.

Russell, Josephine Pease. Interviewed by Bill LaForge, February 24-25, 1989. Oral History 1227, Montana Historical Society, Helena.