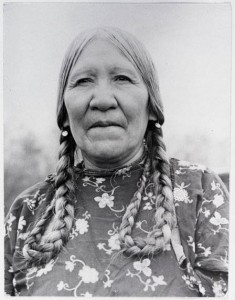

Mary Ann Pierre was about ten years old in October 1891, when American soldiers arrived to “escort” the Salish people out of the Bitterroot region and to the Jocko (now Flathead) Indian Reservation. With her family and three hundred members of her tribe, Mary Ann tearfully left the homeland where her people had lived for millennia. The Salish left behind farms, log homes, and the St. Mary’s Mission church—evidence of all they had done to adjust to an Anglo-American lifestyle. Nearly eighty-five years later, Mary Ann Pierre Coombs returned to the Bitterroot to rekindle her people’s historical and cultural connections to their homeland.

The Bitterroot region and the Salish people share a long mutual history. Salish travel routes to and from the Bitterroot testify to centuries of regular use as they moved seasonally to hunt bison and trade with regional tribes in well-established trading centers. Linguistic studies of the inland Salish language reveal ten-thousand-year-old words that described specific sites in the Bitterroot region and testify to the tribe’s knowledge of the region’s geography and resources.

When Lewis and Clark entered the Bitterroot in 1805 in destitute condition, the hospitable Salish presented the bedraggled strangers with food, shelter, blankets, good horses, and travel advice. In 1841, Jesuit missionaries established St. Mary’s Mission at present-day Stevensville, and many Salish adopted Catholicism alongside their Native beliefs.

In 1855, Washington territorial governor Isaac Stevens negotiated the Hellgate Treaty with the Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai tribes. The necessity of translating everything into multiple languages made the negotiations problematic. One Jesuit observer said the translations were so poor that “not a tenth . . . was actually understood by either party.” While the Kootenai and Pend d’Oreille tribes retained tribal lands at the southern end of Flathead Lake, the fate of the Bitterroot was not clear. Chief Victor believed the treaty protected his Salish tribe from dispossession, as it indicated a future survey for a reservation and precluded American trespass. However, the Americans claimed the treaty permitted the eventual eviction of the Salish at the American president’s discretion.

Continue reading Mary Ann Pierre Topsseh Coombs and the Bitterroot Salish