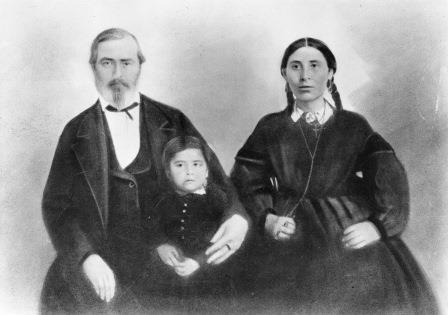

In 1844, influential Piegan warrior Under Bull and his wife, Black Bear, chose American Fur Company clerk Malcolm Clarke to be their teenage daughter Coth-co-co-na’s husband. During their twenty-five year marriage, Coth-co-co-na bore two boys and two girls, moved briefly with Clarke to Michigan, and helped him establish a ranch near Helena. She mourned deeply when Clarke sent their two oldest children east for schooling. In 1862, she accepted Clarke’s new mixed-blood wife, Good Singing, into their home. According to her children’s accounts, her husband’s murder in 1869 left Coth-co-co-na a broken woman. She died in 1895.

For two centuries—from the mid-1600s to the 1860s—Indian and Métis women like Coth-co-co-na brokered culture, language, trade goods, and power on the Canadian and American fur-trade frontier. They were partners, liaisons, and wives to the French, Scottish, Canadian, and American men who scoured the West for salable furs. Stereotyped by early historians as victims or heroines (and there were both), indigenous women also wielded significant, traceable power in this era of changing alliances, increasing intertribal conflict, and expanding European presence in the West.

The roles indigenous women played during the fur trade reflected the roles they historically held within their communities. Despite cultural distinctions among tribes, indigenous women generally shared the common responsibilities of procuring and trading food, hides, and clothing. Women also embodied political diplomacy as tribes forged internal and intertribal relationships around family alliances and cemented these social structures through (often polygamous) marriage. These traditional economic and political roles placed indigenous women at the center of trade, and made them desirable and necessary partners for fur traders.

Continue reading Brokers of the Frontier: Indigenous Women and the Fur Trade