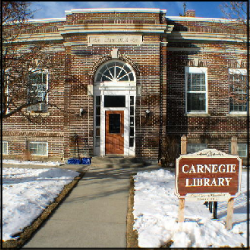

At the January 24, 1914, meeting of the Hamilton Woman’s Club, the club president “presented the idea of the Club boosting for [a] Carnegie Library building here.” Club members concurred and appointed a committee to urge city officials to act. Mrs. J. F. Sullivan, head of the club’s newly formed library committee, approached Hamilton’s city council about asking industrialist and library benefactor Andrew Carnegie for funds. After Marcus Daly’s widow, Margaret, donated the land for the building site, Carnegie’s secretary approved the city’s request. Two years later, the Hamilton Woman’s Club moved its meetings to a specially designated room in the town’s new Carnegie Library, an institution that owed its existence to the clubwomen’s hard work.

The Hamilton Woman’s Club’s instrumental role in the library’s construction is not an isolated case. During the Progressive Era, women’s voluntary organizations frequently led community efforts to build public libraries. In 1933, the American Library Association estimated that three-quarters of the country’s public libraries “owed their creation to women.” More recently, scholars Kay Ann Cassell and Kathleen Weibel have argued that “women’s organizations may well have been as influential in the development of public libraries as Andrew Carnegie,” whose name is carved into thousands of library transoms across the United States.

Since the time of white settlement, Montanans seem to have been unusually passionate about books and libraries. In an 1877 edition of the Butte Miner, one writer noted, “The need for a library was felt here last winter, when aside from dancing there was no amusement whatever to help pass the long, dreary evenings. Dancing, in moderation, will do very well, but it is generally allowed to have been somewhat overdone last winter . . . this library scheme . . . will furnish a means of recreation . . . that is more intellectual and more to be desired in every respect.”

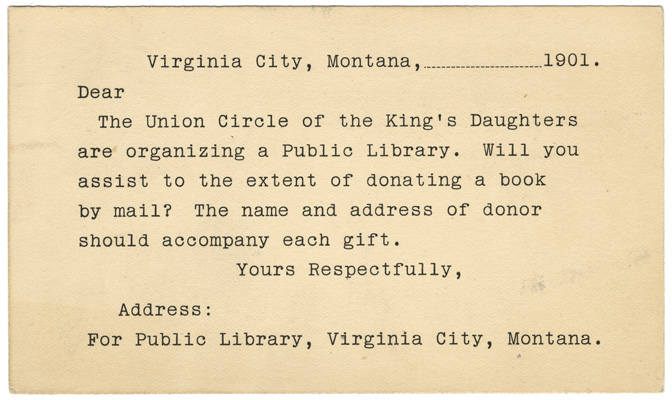

Rising to the call, women’s clubs founded libraries in communities across Montana. Most of these libraries started small: club members donated books, and a local milliner, dressmaker, or hotelier would offer shelf space. As the library (and the community) grew, it often moved to a room in city hall before, finally, opening in a separate building. By 1896 Montana could boast seven public libraries with collections of a thousand volumes or more, and the State Federation of Women’s Clubs maintained a system of traveling libraries.

At the turn of the century, library advocates in Montana received a boost from the Carnegie library grant program, which made funds available for library buildings if communities could prove they would provide a building site and tax support for the library’s ongoing operation. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, seventeen Montana communities built public libraries using Carnegie funds.

The history of Carnegie libraries has been well documented, and this focus has led library historians to emphasize the mayors and city council members who submitted the grant requests to the Carnegie Foundation. While library historian Daniel Ring, for example, acknowledges women’s contributions, he also underestimates their significance. “At least 50 percent of the pre-Carnegie Montana libraries owed their founding to the civic-minded women,” according to Ring, and “When the Carnegie libraries came on the scene, it was usually women’s clubs that alerted the city’s power structure to the idea of obtaining a grant.” However, he emphasizes, “the women could not act alone. Without the support of the male business elite, they were powerless.” Thus, he delegitimizes women’s political activism.

Truly, both men and women worked to establish libraries. However, their motives for engaging in the effort often differed. According to Ring, male politicians who promoted library development typically cared little about libraries as “educational institutions. Rather, the towns’ elites used the libraries as a mechanism to control the new settlers socially, to boost the towns’ fortunes, to exude a sense of permanence, and to bond the new-founded communities socially.” By contrast, the clubwomen who founded public libraries had other intentions. Gender historian Anne Firor Scott concludes that “[w]omen’s work for libraries was closely related to their work for public education.” Members of women’s voluntary associations linked education to self-improvement, and over the course of the nineteenth century they increasingly viewed access to education as a key to “breaking the cycle of poverty.”

Like many scholars of women’s history, Scott recognizes that “Historians, looking at the past, do not see all that is there.” Until recently, historians have overlooked and underestimated women’s contributions to library development—in Montana and elsewhere—as well as their work sustaining libraries after construction. Members of the Miles City Woman’s Club, for example, made fund-raising for the town’s Carnegie Library their “main objective” after the building was completed in 1902. And they were not alone. Today, East Glacier still relies on woman’s club volunteers to staff its library.

Montana’s clubwomen played a crucial role in community improvement and educational development in the early twentieth century. Putting women back at the center of the state’s library history sheds light on their achievements and offers recognition that is long overdue. AH

Learn more about the Red Lodge Carnegie Library (and other historic sites related to women’s history) on our Places page.

Sources

Barger, J. Wheeler. “The County Library in Montana.” Bulletin no. 219, University of Montana Agricultural Experiment Station, Bozeman, Montana, January 1929. Copy in Libraries, Public, vertical file. Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Hamilton [Montana] Woman’s Club Records, 1913-1989. MC 212, Montana Historical Society Research Center.

Martin, Marilyn. “From Altruism to Activism: The Contributions of Literary Clubs to Arkansas Public Libraries.” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 55, no. 1 (Spring 1996), 64-94.

Richards, Susan. “Carnegie Library Architecture for South Dakota and Montana: A Comparative Study.” Journal of the West, July 1991, 69-78. Copy in Libraries, Montana, vertical file, Montana Historical Society Research Center.

Ring, Daniel. “Carnegie Libraries as Symbols for an Age: Montana as a Test Case.” Libraries & Culture 27, no. 1 (Winter 1992), 1-19.

Scott, Anne Firor. “On Seeing and Not Seeing: A Case of Historical Invisibility.” The Journal of American History 71, no. 1 (June 1984), 7-21.

________. “Women and Libraries.” The Journal of Library History 21, no. 2 (Spring 1986), 400-405.

Smith, Clare M. “Miles City Carnegie Library.” The Montana Woman, April 1968, 9. Copy in Libraries, Montana, vertical file, Montana Historical Society Research Center.