The legacy of a nineteenth-century Apsáalooke grandmother lives on in the traditions of the Crow people today. Born in 1856, Pretty Shield belonged to the last generation of children raised in an intact Apsáalooke culture. Just thirty years later, the tribe faced the loss of their indigenous identities and cultural heritage as well as their lands. Thus, by the 1920s and 1930s, as she raised her grandchildren, Pretty Shield confronted a twofold challenge: first, to bring them up in the poverty of the early reservation years; second, to instill in them a strong Apsáalooke identity during the era of assimilation. She was well aware of the difficulty—and importance—of her task.

Pretty Shield herself had enjoyed a happy childhood. Her elders taught her how to harvest plants, preserve meat, cook, and sew. They guided her spiritually, educated her, and brought her up according to the traditions of the Apsáalooke worldview. Too soon, these happy years gave way to the destructive forces of American colonization.

In 1872, smallpox killed hundreds of Crow people, including Pretty Shield’s beloved father, Kills in the Night. At the same time, American military campaigns against other Plains tribes threatened all intertribal trade and safety while the extinction of the bison destroyed tribal economies. Reduced to poverty and starvation, tribes were forced to relinquish more and more of their homelands. Between 1851 and 1904, the Crows themselves lost 35 million acres. The U.S. government outlawed indigenous ceremonies, mandated that Native children attend government or mission schools, and sent emissaries of assimilation onto the reservations to enforce American policies. Many Crows converted to Christianity, took up farming, and sent their children to be raised at boarding schools, where their Apsáalooke identity succumbed to white American values and a wholly different relationship to the natural world.

Pretty Shield refused to surrender the Apsáalooke way of life. When her daughter, Helen Goes Ahead, died in 1924 of an untreated infection, Pretty Shield accepted the responsibility of caring for her grandchildren, including one-year-old Alma. She was determined to raise Alma as she herself had been raised and surrounded her with other traditional women. She also kept Alma out of the government school as long as possible, having Alma feign illness whenever school officials visited. While teaching Alma the practical means of survival, Pretty Shield also shared a worldview that was at risk of dying with her generation.

“I became what the Crows call káalisbaapite—a ‘grandmother’s grandchild’,” Alma recalled in later years. “I learned how to do things in the old ways. While the mothers of my friends changed to modern ways of preparing things, Pretty Shield stuck to her old ways. . . . While my grandmother was teaching me her ways of the past, how they survived and their traditional and cultural values, mothers of other girls were teaching them to adapt.”

Eventually, Pretty Shield was forced to send Alma to school, where the girl enjoyed literature and drama. She learned to sing arias from operas, to tap dance, and to play basketball. She joined the Girl Scouts. But when Alma reached seventh grade, the principal sent her to Flandreau Indian School in South Dakota. There, she spoke only English, attended Christian church services, and could not follow the customs Pretty Shield had taught her. She adopted the clothing, hairstyle, and behavior of white American teenagers. It seemed that each year Alma lost more of her Apsáalooke identity, and Pretty Shield grieved: “They want all our children to be educated in their way. . . . That makes me sad,” she said, “because I am going to have to let the old ways go and push my children into this new way. . . . It hurts and I feel so helpless. It’s just as if I am nothing. . . . I am at the brink of no more.”

When Pretty Shield passed away in 1944, doctors told Alma that her eighty-eight-year-old grandmother had died of old age, but Alma believed her grandmother had died of a broken heart, grieving the destruction of the Apsáalooke way of life.

In 1946, Alma moved to Fort Belknap, where she married Bill Snell, an Assiniboine. Caught up in the day-to-day work of ranch life and raising children in the 1950s and 1960s, she began to lose sight of her cultural heritage. Then she had a dream that helped her recognize the value of Pretty Shield’s teachings. In the dream a young and radiant Pretty Shield appeared to her, surrounded by light. When Alma awoke, she held a freshly dug wild turnip in her hand and realized that Pretty Shield had entrusted her with knowledge that had to be shared if Apsáalooke culture was to remain alive.

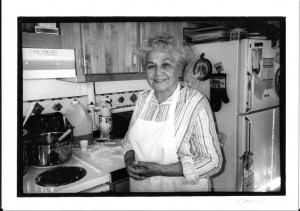

Snell devoted the rest of her life to teaching others what she had learned about medicinal plants, healing, and Crow culture. “I have a push in my heart to keep up the Indian cultural values. I’m sure Pretty Shield is the source of that push,” she wrote in 2006 in a book on Native herbal medicine. Among the book’s botanical descriptions and recipes are vivid recollections of her grandmother—testimony to Pretty Shield’s importance in her life.

Before her death in 2008, Montana State University awarded Alma Snell an honorary doctorate, testimony to the knowledge she had shared with the world. LF

Theresa Walker Lamebull was another woman who played a critical role in the preservation of her culture. Read more about her efforts to preserve the Gros Ventre language in Theresa Walker Lamebull Kept Her Language Alive.

Want to learn more about the lives of Montana Indian women? Read some of the titles listed on this Bibliography of Resources about Native American and Métis Women in Montana.

Sources

“Alma Hogan Snell” (obituary). Billings Gazette, May 6, 2008. Accessed May 13, 2013.

Linderman, Frank Bird. Pretty Shield, Medicine Woman of the Crows (reprint). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Pretty Shield Foundation. Accessed September 1, 2013.

Snell, Alma. Grandmother’s Grandchild: My Crow Indian Life. Edited by Becky Matthews. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

—. A Taste of Heritage: Crow Indian Recipes and Herbal Medicines. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.