The first telephone arrived in Montana in 1876, the same year Alexander Graham Bell patented his invention, and by the 1890s many Montana cities had telephone exchanges. According to Ellen Arguimbau, author of “From Party Lines and Barbed Wire: A History of Telephones in Montana,” early telephones needed to be connected directly by wire. To facilitate that connection, telephone companies established exchanges, staffed almost entirely by young female operators. “The caller telephoned the operator and asked to be connected to someone. The operator then plugged the wire into the call recipient’s slot.”

Arguimbau describes the working conditions of these female employees in “Number, please,” originally published in Montana The Magazine of Western History and excerpted below.

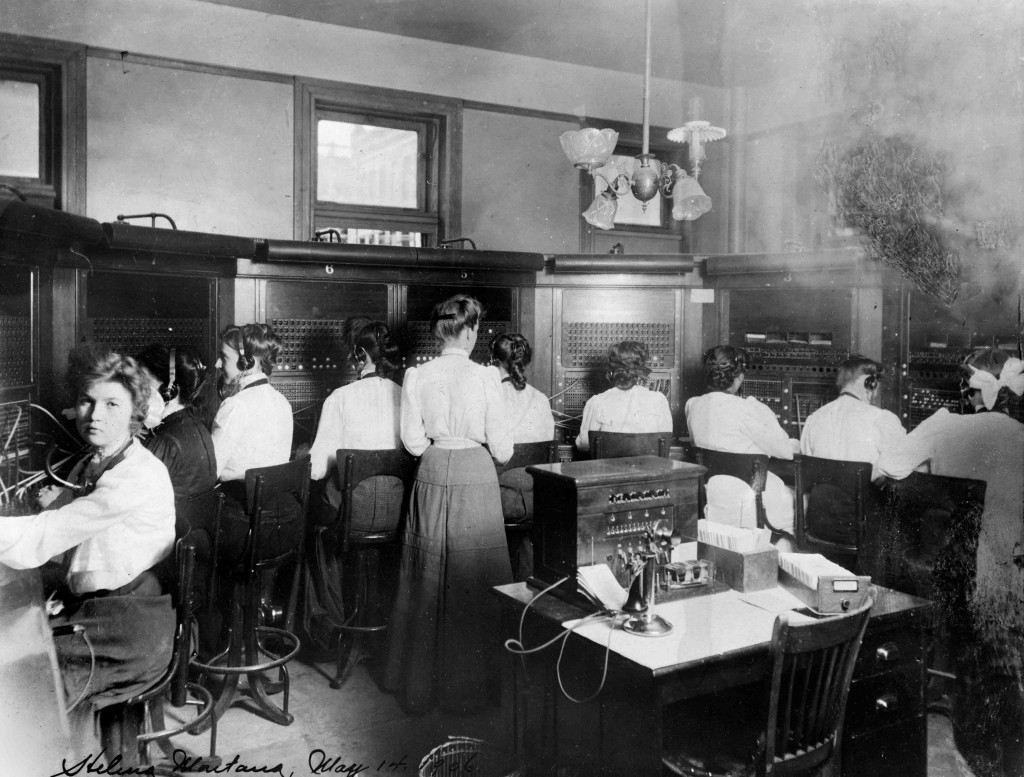

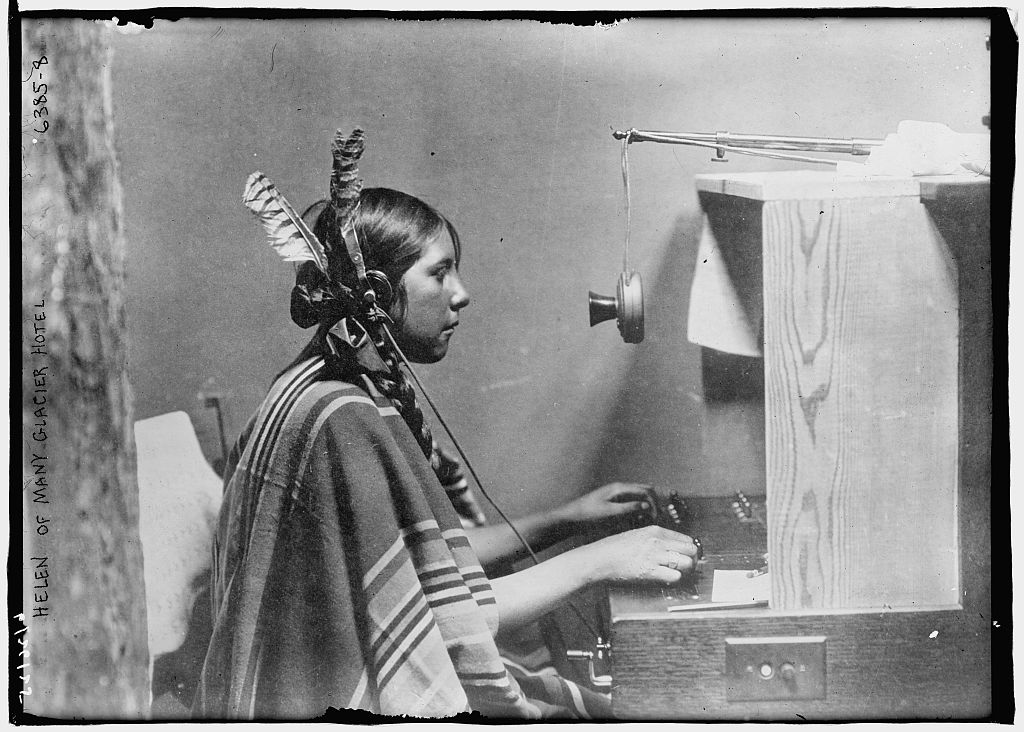

Often a maze of cords and sockets, switchboards were attended by one operator in a small exchange or by a roomful of operators in the larger towns, usually all young women. According to a 1902 U.S. Census Bureau report: “For many years it has been recognized that operators’ work in telephone exchanges attracts a superior class of women. It has been demonstrated beyond all doubt that the work of operating is better handled by women than by men or boys and that trained and well-bred women operators perform the most satisfactory service.”

Although female telephone operators may have been recognized for their abilities, they often worked long hours for very low pay. For example, in 1907 Rocky Mountain Bell operators’ wages were frequently as low as thirty to forty dollars per month for a ten- to twelve-hour day. That year, Butte operators struck for higher wages and an eight-hour day, and the company, in recognition of their united strength, almost immediate agreed to a minimum wage of fifty dollars per month, an eight-hour day, and a closed shop. That same year, the legislature enacted a law banning the employment of girls under the age of sixteen as telephone operators and in 1909 limited the hours of telephone operators to nine hours per day in cities and towns of more than three thousand people, except under special circumstances of illness or emergency.

Dorothy Johnson worked as an operator in Whitefish starting in 1919. She described her experience:

The board was a vast expanse of eyes, with, at the base, a dozen or so pairs of plugs on cords for connecting and an equal number of keys for talking, listening, and ringing. On a busy day these cords were woven across the board in a constantly changing, confusing pattern; half the people using telephones were convinced that Central was incompetent or hated them, and Central—flipping plugs into holes, ringing numbers, trying to remember whether 44 wanted 170-K or 170-L, because if she went back and asked him, he’d be sure she was stupid—was close to hysterics. It was every operator’s dream that when her ship came in she would open all the keys on a busy board, yell “To hell with you,” pull all the plugs, and march out in triumph, leaving everything in total chaos. Nobody ever did. We felt an awful responsibility toward our little corner of the world. We really helped keep it running, one girl at a time all by herself at the board.

– EA

Read Dorothy Johnson’s reminiscence, “Confessions of a Telephone Girl,” in Montana The Magazine of Western History 47, no. 4 (Winter 1997): 68-75. You can find links to the full text of all Montana The Magazine of Western History articles relating to women’s history here.

After her brief stint as a telephone operator, Dorothy Johnson went on to become a premier Western novelist. Read about her later career here.

Sources

Arguimbau, Ellen. “From Party Lines and Barbed Wire: A History of Telephones in Montana,” Montana The Magazine of Western History63 no. 3 (Autumn 2012): 34-45.