Temperance advocate Carrie Nation once pronounced Mary MacLane “the example of a woman who has been unwomanly in everything that she is noted for.” MacLane was no doubt delighted with the description. Writer, bohemian, and actress, Mary MacLane (1881-1929) was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and grew up in Butte, Montana. Best known for her two autobiographical books, The Story of Mary MacLane (1902) and I, Mary MacLane (1917), she also wrote features for newspapers, starred in a motion picture, and became notorious for her outrageous, unwomanly behavior.

MacLane was the child of failed fortune. Her father died when she was eight; after her mother remarried, her stepfather took the family to Butte in search of riches. According to legend, on the eve of Mary’s departure for Stanford University, her stepfather confessed that he had lost the family’s money in a mining venture and could not afford to send her to college. Whatever the truth, Mary did not attend college after graduating from Butte High School, but spent her days feeling restless and trapped, walking through Butte and recording her thoughts in her diary. In 1902, she sent the handwritten text to a Chicago publisher, Fleming H. Revell Co, under the title, I Await the Devil’s Coming. The editor who read the piece judged it the “most astounding and revealing piece of realism I had ever read.” But it was not the kind of material that the Revell, “Publishers of Evangelical Literature,” brought to the market. Fortunately, the editor sent it to another publisher, Stone & Kimball, who released it as The Story of Mary MacLane. Within a few months the book had sold eighty thousand copies, and MacLane may have earned as much as $20,000 in royalties in 1902 (approximately $500,000 in 2013 dollars).

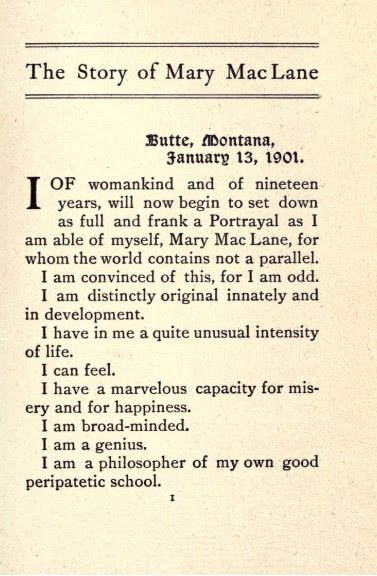

The book challenged the notions of what proper young middle-class women were supposed to think and feel. In an age when legs were referred to as limbs, Mary boasted of her strong woman’s body; in an era of moral absolutes, she claimed that right, wrong, good, and evil were mere words. She titillated and outraged readers when she claimed that she wanted not merely romance but seduction. And above all, she craved “Experience”:

“It is not deaths and murders and plots and wars that make life tragedy.

It is Nothing that makes life tragedy.

It is day after day, and year after year, and Nothing.

It is a sunburned little hand reached out and Nothing put into it.”

Declaring herself “earthy, human, sensitive, sensuous, and sensual,” she prayed that she would never become “that deformed monstrosity—a virtuous woman.”

The book and its author became sensations across the country. The Butte Public Library banned The Story of Mary MacLane, and a daily paper denounced it as “inimical to public morality.” The New York Herald pronounced MacLane mad and demanded that paper and pen be denied her until she regained her senses. The New York Times advised a spanking. The book’s popularity and Mary’s narcissism spawned parodies such as Damn! The Story of Willie Complain and The Devil’s Letters to Mary MacLane, By Himself. A vaudeville team created a popular routine, “The Story of Mary McPaine.”

Using royalties from book sales, MacLane left Butte and moved to the East Coast. She was barraged by the press in Chicago and spent time in Greenwich Village, where she reveled in the company of other free-spirited women. She wrote about male lovers and her physical attractions to women. At some time in the late summer or fall of 1902, she met Caroline Branson, the former partner of writer Mary Louise Pool, and began a six-year relationship with her, the only long-term romance MacLane ever had. She published another book in 1903, My Friend Annabel Lee, but it received poor reviews and garnered few sales.

Broke and having written nothing of substance for some time, in 1909 she returned to Butte, where she remained for seven years, haunting gambling dens and roadhouses. Betty Horst recalled the time her father, Butte’s health officer, rented a hack to take his wife to a roadhouse for dinner. As they walked through the bar toward the dining room, they passed MacLane sitting at a slot machine, smoking and drinking. She invited Mrs. Horst to join her. When Mrs. Horst accepted, her shocked husband continued into the restaurant. When it sank in that his wife actually knew Butte’s notorious female writer, Dr. Horst got up and drove home.

While in Butte, MacLane wrote another autobiographical book, I, Mary MacLane, released in 1917, and wrote and starred in a silent film, “Men Who Have Made Love to Me.” But what was sensational in 1902 seemed self-indulgent in 1917. Sales of I, Mary MacLane were disappointing; Mary had no future as an actress, and she never again published. Deliberately cutting herself off from friends and family, plagued by poverty, she lived quietly in boardinghouses and hotels in Chicago until her death in 1929. When the hotel manager discovered her body, clippings and photographs from her glory days surrounded it. MM

The Story of Mary MacLane has been reprinted and is available in both paper and Kindle editions. It is available for free through the Internet Archives.

Read more about Mary MacLane in “Mary MacLane: A Feminist Opinion” and “Montana’s Shocking ‘Lit’ry Lady,” both published in Montana The Magazine of Western History.

Learn about a few of Montana’s less controversial women authors in Writing a Rough-and-Tumble World: Caroline Lockhart and B. M. Bower and A “Witty, Gritty Little Bobcat of a Woman”: The Western Writings of Dorothy M. Johnson.

Sources

Halvorsen, Cathryn Luanne. “Autobiography, Genius, and the American West: The Story of Mary MacLane and Opal Whiteley.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1997.

MacLane, Mary. I, Mary MacLane. New York: F. A. Stokes, 1917.

________. The Story of Mary MacLane. Chicago: Herbert S. Stone, 1902.

Mattern, Carolyn J. “Mary MacLane: A Feminist Opinion.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 27, no.4 (Autumn 1977), 54-63.

Murphy, Mary. Mining Cultures: Men, Women and Leisure in Butte, 1914-1941. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Tovo, Kathryne Beth. “’The Unparalleled Individuality of Me’: The Story of Mary MacLane.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 2000.

Wheeler, Leslie. “Montana’s Shocking ‘Lit’ry Lady.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 27, no.3 (Summer 1977), 20-33.

Martha Edgerton Rolfe Plassmann once wrote that Mary MacLane was fifty years ahead of her time. Young Mary lived her early teen years in Great Falls before her step father moved the family to Butte seeking mining fortunes. The Great Falls newspapers always treated Mary as a home town girl as in the shortened article from the 26 Nov 1902 edition: ” Mary Elizabeth MacLane A Former Great Falls Girl Who Claims She Is a Genius. Miss Mary Elizabeth MacLane says she is a genius. She lived in Great Falls for five years, and her genius was not suspected by those who knew her in that time, but she was then a bashful schoolgirl, who had not realized her capabilities, and she took no pains to make others believe in her. Her older sister, Dorothy, was considered very bright, as well as the beauty of the family, but a few years have shown that each possesses both beauty and brains, and from Butte, their present home, comes the report that Dorothy has developed into one of the most beautiful girls of the state, while Mary is not only very good looking, but also claims to be a genuine genius. She is a little over 20 years of age now, and she is a seeker after fame, determined to achieve it if she merits it, and she has full confidence she does.

The girls are stepdaughters of H. G. Klenze and while in Great Falls lived at 1112 Third avenue north, and attended public schools, both being in the High school when the family left here in the spring of 1896. Both were later graduated from the Butte High school, where each stood very high in her studies. There are also two boys in the family; Jack was a member of one of the Butte companies of the First Montana volunteers and was for a time a color sergeant of the regiment, and Jimmie, the youngest, is now about 18 years of age and very much like his sisters in many ways. . . .

This genius of Butte is Mary Elizabeth MacLane, and she lives on North Excelsior avenue. As she has set down in the portrayal: ‘I was born in 1881 at Winnipeg, in Canada, and whether Winnipeg will yet live to be proud of this fact is a matter for some conjecture. When I was three years old I was taken with my family to a little town in western Minnesota, where I lived a more or less vapid and ordinary life until I was 10. We came then to Montana, whereat the aforesaid life was continued. I am purely of the MacLane blood, which is Highland Scotch. These particular MacLanes are just a little bit different from every family in Canada. It contains and contained fanatics of many minds—religious, social, what not—and I am a true MacLane. There are a great many MacLanes, but there usually is only one real MacLane in each geeration. There is but one who feels again the passionate spirit of the clans, those barbaric dwellers in the bleak and well beloved Highlands of Scotland. I am the real MacLane of my generation. The real Maclane in these later centuries is always a woman.

‘I graduated from the Butte High school with these things: Very good Latin, good French and Greek, some little geometry and other mathematics, a broad conception of history and literature, peripatetic philosophy that I acquired without any aid from the High school, genius of a kind that has always been with me, an empty heart that has taken on a certain wooden quality, an excellent, strong young woman’s body, a pitiably starved soul.’” [GFTD 6 Apr 1902, p. 11]

Thanks for sharing!

You clearly have done some significant research on MM – we should talk. (I just discovered that she and her family lived in Neihart prior to Great Falls.) I trust you’ve heard about out various MM volumes coming out shortly?

Love this Organisation. Would enjoy “liking” it on Facebook.

Join us on Facebook, Ellen: https://www.facebook.com/montanawomenshistory.

Oh, and I just noticed – the link to Leslie Wheeler’s outstanding article actually links to her (also excellent) article on Gertrude Atherton.

Corrected! Thanks for pointing out the mistake.

I think it’s still pointing to the Atherton article. 😮

P.S. – Check the big new MM website below.

Damn. Ghost in the machine. It should be right now.

Can anyone point to MacLane’s newspaper article in which she mentions Inez Haynes Irwin Gillmore? It is mentioned but difficult to find the article, itself. Thank you.

Just saw this comment! I don’t believe M.M. mentions Inez in a feature article, but she does mention her in her last book “I, Mary MacLane” – “It’s nice to get an unexpected letter from Jane Gillmore.” She does mention Inez in her private letters – says Inez does very good short stories.

Additionally, she included a portrayal of Inez without using her name in “The Borrower of Two-Dollar Bills – and Other Women” – Butte Evening News – 15 May 1910: The Literary Woman – I just knew her in Boston – a friend of mine for years, a girl of about thirty, with a pallid husband who was a secondary interest, her first being her work, which was short stories, for which she had made a distinct market. She was rather beautiful in a foreign-looking way, with a small svelte body, a complexion of rose-and-bronze, and eyes like hazel-colored half-glacial windows to her mind. She had spasmodic warmths of heart (I was, and am, fond of her), but I should hate to be wholly dependent on one of her ilk for the light o’ love. This her line of talk: “MacTrey, I don’t know just how you look at it, but to me the two most worthwhile things in God’s world are Fame and Freedom. If I were to be granted three wishes this instant, this instant I should say: Fame, Freedom, and the ability I feel in me now to appreciate them absolutely to their last pitch. I know I’ll never be free – I’ll always be held down by a hundred fetters, because I’m afraid. But I fully intend to be famous, if it isn’t till I’m fifty. I’ve made me a short-story reputation in four years, by just keeping on hammering my typewriter and bucking the literary game. As for you, MacTrey, I don’t quite get your attitude, and perhaps you’ll say it’s none of my business, but I can’t help thinking you’re squandering and dissipating your life on these experiences of yours – you seem to pay so high and to such an insatiate piper. In your place, what wouldn’t you do? You’ve proved you’re not afraid of anything the world can hand you and you’ve got, at an age which seems to me just like being a little girl, your own particular niche of fame. With that you might do anything – you might make even this big flinty New York sit up and rub its eyes and stare till they dropped out – you could put it all over the two million other sulphites. But instead of that you madly flit about after silver-and-scarlet butterflies. For what you have only to stretch out a languid hand and take, I’d give my useless soul for.” “Jane,” said I, “don’t be a bore. Let’s go over to Keith’s and see Yvette Gilbert, she goes on at three. She has an exquisite French sort of pathos about her which will take your mind off me.” “Yes, I want to see her,” she replied, “I want to study her type a little. It’s distinctly European. But I’d like still more to give you a much-needed spanking.” A good sort, the rose-and-bronze, but if you ask me, a sort which misses the pink honey of life. There are many like her in New York.

Hope this helps! Write me with any questions.