Temperance advocate Carrie Nation once pronounced Mary MacLane “the example of a woman who has been unwomanly in everything that she is noted for.” MacLane was no doubt delighted with the description. Writer, bohemian, and actress, Mary MacLane (1881-1929) was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and grew up in Butte, Montana. Best known for her two autobiographical books, The Story of Mary MacLane (1902) and I, Mary MacLane (1917), she also wrote features for newspapers, starred in a motion picture, and became notorious for her outrageous, unwomanly behavior.

MacLane was the child of failed fortune. Her father died when she was eight; after her mother remarried, her stepfather took the family to Butte in search of riches. According to legend, on the eve of Mary’s departure for Stanford University, her stepfather confessed that he had lost the family’s money in a mining venture and could not afford to send her to college. Whatever the truth, Mary did not attend college after graduating from Butte High School, but spent her days feeling restless and trapped, walking through Butte and recording her thoughts in her diary. In 1902, she sent the handwritten text to a Chicago publisher, Fleming H. Revell Co, under the title, I Await the Devil’s Coming. The editor who read the piece judged it the “most astounding and revealing piece of realism I had ever read.” But it was not the kind of material that the Revell, “Publishers of Evangelical Literature,” brought to the market. Fortunately, the editor sent it to another publisher, Stone & Kimball, who released it as The Story of Mary MacLane. Within a few months the book had sold eighty thousand copies, and MacLane may have earned as much as $20,000 in royalties in 1902 (approximately $500,000 in 2013 dollars).

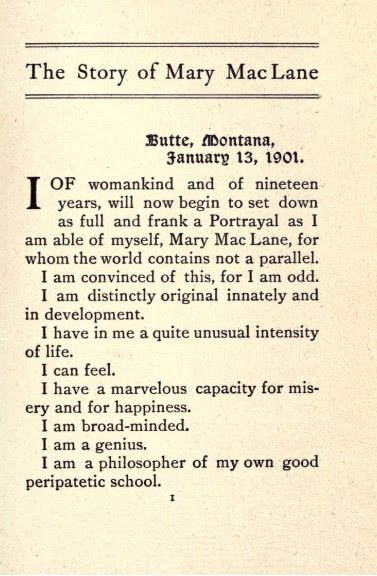

The book challenged the notions of what proper young middle-class women were supposed to think and feel. In an age when legs were referred to as limbs, Mary boasted of her strong woman’s body; in an era of moral absolutes, she claimed that right, wrong, good, and evil were mere words. She titillated and outraged readers when she claimed that she wanted not merely romance but seduction. And above all, she craved “Experience”:

“It is not deaths and murders and plots and wars that make life tragedy.

It is Nothing that makes life tragedy.

It is day after day, and year after year, and Nothing.

It is a sunburned little hand reached out and Nothing put into it.”

Declaring herself “earthy, human, sensitive, sensuous, and sensual,” she prayed that she would never become “that deformed monstrosity—a virtuous woman.”

The book and its author became sensations across the country. The Butte Public Library banned The Story of Mary MacLane, and a daily paper denounced it as “inimical to public morality.” The New York Herald pronounced MacLane mad and demanded that paper and pen be denied her until she regained her senses. The New York Times advised a spanking. The book’s popularity and Mary’s narcissism spawned parodies such as Damn! The Story of Willie Complain and The Devil’s Letters to Mary MacLane, By Himself. A vaudeville team created a popular routine, “The Story of Mary McPaine.”

Using royalties from book sales, MacLane left Butte and moved to the East Coast. She was barraged by the press in Chicago and spent time in Greenwich Village, where she reveled in the company of other free-spirited women. She wrote about male lovers and her physical attractions to women. At some time in the late summer or fall of 1902, she met Caroline Branson, the former partner of writer Mary Louise Pool, and began a six-year relationship with her, the only long-term romance MacLane ever had. She published another book in 1903, My Friend Annabel Lee, but it received poor reviews and garnered few sales.

Broke and having written nothing of substance for some time, in 1909 she returned to Butte, where she remained for seven years, haunting gambling dens and roadhouses. Betty Horst recalled the time her father, Butte’s health officer, rented a hack to take his wife to a roadhouse for dinner. As they walked through the bar toward the dining room, they passed MacLane sitting at a slot machine, smoking and drinking. She invited Mrs. Horst to join her. When Mrs. Horst accepted, her shocked husband continued into the restaurant. When it sank in that his wife actually knew Butte’s notorious female writer, Dr. Horst got up and drove home.

While in Butte, MacLane wrote another autobiographical book, I, Mary MacLane, released in 1917, and wrote and starred in a silent film, “Men Who Have Made Love to Me.” But what was sensational in 1902 seemed self-indulgent in 1917. Sales of I, Mary MacLane were disappointing; Mary had no future as an actress, and she never again published. Deliberately cutting herself off from friends and family, plagued by poverty, she lived quietly in boardinghouses and hotels in Chicago until her death in 1929. When the hotel manager discovered her body, clippings and photographs from her glory days surrounded it. MM

The Story of Mary MacLane has been reprinted and is available in both paper and Kindle editions. It is available for free through the Internet Archives.

Read more about Mary MacLane in “Mary MacLane: A Feminist Opinion” and “Montana’s Shocking ‘Lit’ry Lady,” both published in Montana The Magazine of Western History.

Learn about a few of Montana’s less controversial women authors in Writing a Rough-and-Tumble World: Caroline Lockhart and B. M. Bower and A “Witty, Gritty Little Bobcat of a Woman”: The Western Writings of Dorothy M. Johnson.

Sources

Halvorsen, Cathryn Luanne. “Autobiography, Genius, and the American West: The Story of Mary MacLane and Opal Whiteley.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1997.

MacLane, Mary. I, Mary MacLane. New York: F. A. Stokes, 1917.

________. The Story of Mary MacLane. Chicago: Herbert S. Stone, 1902.

Mattern, Carolyn J. “Mary MacLane: A Feminist Opinion.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 27, no.4 (Autumn 1977), 54-63.

Murphy, Mary. Mining Cultures: Men, Women and Leisure in Butte, 1914-1941. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Tovo, Kathryne Beth. “’The Unparalleled Individuality of Me’: The Story of Mary MacLane.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 2000.

Wheeler, Leslie. “Montana’s Shocking ‘Lit’ry Lady.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 27, no.3 (Summer 1977), 20-33.