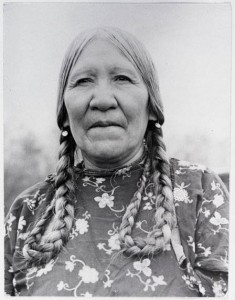

Mary Ann Pierre was about ten years old in October 1891, when American soldiers arrived to “escort” the Salish people out of the Bitterroot region and to the Jocko (now Flathead) Indian Reservation. With her family and three hundred members of her tribe, Mary Ann tearfully left the homeland where her people had lived for millennia. The Salish left behind farms, log homes, and the St. Mary’s Mission church—evidence of all they had done to adjust to an Anglo-American lifestyle. Nearly eighty-five years later, Mary Ann Pierre Coombs returned to the Bitterroot to rekindle her people’s historical and cultural connections to their homeland.

The Bitterroot region and the Salish people share a long mutual history. Salish travel routes to and from the Bitterroot testify to centuries of regular use as they moved seasonally to hunt bison and trade with regional tribes in well-established trading centers. Linguistic studies of the inland Salish language reveal ten-thousand-year-old words that described specific sites in the Bitterroot region and testify to the tribe’s knowledge of the region’s geography and resources.

When Lewis and Clark entered the Bitterroot in 1805 in destitute condition, the hospitable Salish presented the bedraggled strangers with food, shelter, blankets, good horses, and travel advice. In 1841, Jesuit missionaries established St. Mary’s Mission at present-day Stevensville, and many Salish adopted Catholicism alongside their Native beliefs.

In 1855, Washington territorial governor Isaac Stevens negotiated the Hellgate Treaty with the Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai tribes. The necessity of translating everything into multiple languages made the negotiations problematic. One Jesuit observer said the translations were so poor that “not a tenth . . . was actually understood by either party.” While the Kootenai and Pend d’Oreille tribes retained tribal lands at the southern end of Flathead Lake, the fate of the Bitterroot was not clear. Chief Victor believed the treaty protected his Salish tribe from dispossession, as it indicated a future survey for a reservation and precluded American trespass. However, the Americans claimed the treaty permitted the eventual eviction of the Salish at the American president’s discretion.

Following Chief Victor’s death in 1870, President U. S. Grant issued an executive order demanding the Salish remove to the Flathead and sent General James Garfield in 1872 to force their consent. When Victor’s son, Chief Charlo, refused to sign the “agreement,” Garfield forged Charlo’s “X” on the document and the United States seized most of the tribe’s land. Three hundred Salish people refused to leave, and instead worked hard to maintain peace with the increasing number of intruding whites. Many Salish families, including the Mary Ann’s, built log homes, took up farming, planted orchards and vegetable gardens, and minimized their traditional seasonal travels. Her family got along well with their white neighbors. The Salish even refused aide to their allies, the Nez Perce, during that tribe’s conflicts with the United States in 1877. The Salish hoped that such efforts to maintain good relations would appease the Americans’ determination to drive them from their homeland.

Over the next twenty years, however, Americans continued to trespass into the disputed territory, establishing new towns and building a railroad for the timber industry. Just after Montana became a state, Congress ordered General Carrington and his soldiers to remove Chief Charlo’s tribe to the Flathead. On October 14, 1891, armed soldiers evicted three hundred Salish, some of whom left on foot. Later, Mary Ann recalled that “everyone was in tears, even the men,” and said the procession was like “a funeral march.” Other elders who had been children at the time of the removal remembered women weeping as American troops marched them through Stevensville in front of white onlookers.

The government promised to compensate the Bitterroot Salish for the homes, crops, and livestock they left behind, but it was an empty promise. So, too, was the government’s promise to provide for their survival on the Flathead Reservation. Mary Ann’s family lived in poverty on the new reservation, where the rocky soil made farming difficult.

Mary Ann attended two years at the Jocko agency school, but never learned to speak English fluently. As a teenager she worked as a laundry maid for Indian Agent Peter Ronan’s family. While working for the Ronans, she met Louis Topsseh Coombs, whom she later married. They raised a family on the Flathead Reservation, and many years passed before Mary Ann Coombs returned to the Bitterroot.

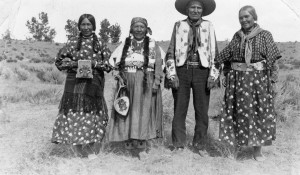

By the 1970s, only three of the hundreds of Salish people who had made the sorrowful trek from the Bitterroot to the Flathead were still alive, among them Mary Ann Coombs. In 1975, those three joined several descendants on a trip back to the Bitterroot. During the journey the elders recounted childhood memories and tribal histories associated with particular places. They visited the graves of ancestors and showed younger relatives places where generations of Salish people had gone to receive medicine through visions.

Recently, Montana’s Fish, Wildlife and Parks and the Metcalf Wildlife Preserve relied on oral histories passed down by Coombs and her peers to create interpretive signs describing Salish history throughout the Bitterroot. The tribe has created an extensive project to map and record historical Salish sites using ancient place-names. Although Mary Ann Pierre Topsseh Coombs—who once woke up to see the red tops of the mountains of her homeland—is gone, the Salish peoples’ connections to the Bitterroot remain. LKF

Sources

Adams, Louis. “Salish Removal from the Bitterroot Valley.” Lewis & Clark Trail – Tribal Legacy Project (transcript of video). Video of same. Accessed November 5, 2013.

“Ancestors Remembered during Bitterroot Valley Treks.” Char-Koosta News, September 22, 2000, 1.

Azure, B. L. “Bitterroot Culture Camp to Expose Non-Indian Youth to the History and Culture of the Bitterroot Salish.” Char-Koosta News, June 9, 2011, 12.

Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. Fire on the Land (DVD). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 2006.

Hill, Lonny. “Treaty History: Chief Charlo Marched from the Bitterroot.” Char-Koosta News, July 30, 1999, 7.

Matt, Don. “Mary Ann Topsseh Coombs.” Char-Koosta News, November 15, 1975, 7-8.

“New Interpretive Signs Touch on Salish History.” Char-Koosta News, September 3, 1993, 4.

Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. “Council Grove: Site of the Hellgate Treaty of 1855.” Accessed February 17, 2014.

Salish and Kootenai Tribes Fire History Project. “Native Peoples and Fire” (website). See especially, “Fire and the Forced Removal of the Salish People from the Bitterroot Valley.” Accessed February 18, 2014.

Salish Culture Committee. The Salish People and Lewis and Clark. Pablo, Mont.: Salish Kootenai Press, 2013

Salish Kootenai College. Challenge to Survive: History of the Salish Tribes of the Flathead Indian Reservation, Victor and Alexander Period 1840-1870. Pablo, Mont.: Salish Kootenai College Press, 2008.

Sessions, Patti. “Tribal Monument Dedicated Monday.” Char-Koosta News, October 18, 1991, 1.

“Treaty of Hellgate, July 16, 1855.” Text at Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes website. Accessed February 11, 2014.