Although Montana midwives had a long history of working with doctors to serve the needs of women in their communities, their profession—and especially the idea of home birth—faded from mainstream acceptance as the hospital replaced the home as the “normal” birthing location. By the 1950s, a majority of women across the United States delivered their babies in hospitals. Even as hospital births became more common, midwives continued to assume that pregnancy and delivery were nonmedical events. Physicians, on the other hand, began to insist that medical assistance and access to technology were necessary for safe deliveries.

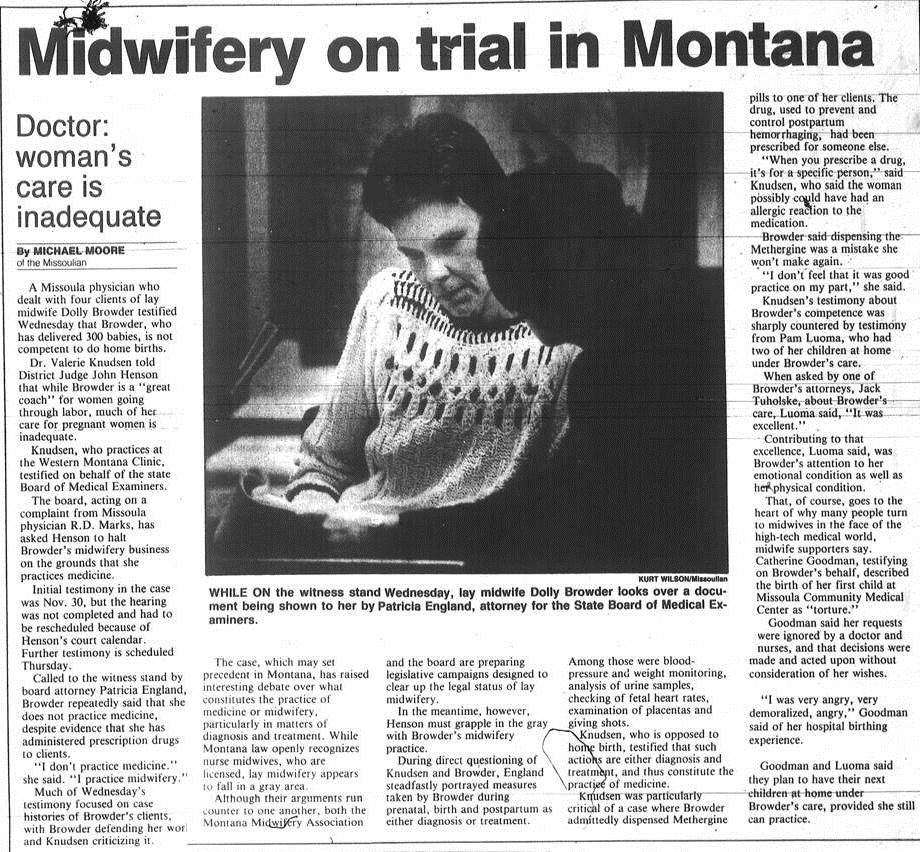

The conflict crystalized in 1988 when the Montana Board of Medical Examiners, at the request of a Missoula physician, pressed charges against a Montana midwife, Dolly Browder, and initiated a court case, accusing her of violating the Medical Practice Act by practicing medicine without a license.

After a three-day civil trial, the Missoula judge ruled against Browder. He concluded that she was practicing medicine and banned her from assisting pregnant women. The case concluded in January 1989, just as the Fifty-first session of the Montana legislature convened. With the looming threat of additional lawsuits, the Montana Midwifery Association hired a lobbyist, raised funds, and organized supporters. Their goal: To change the Montana Medical Practice Act to exempt home birth midwifery.

Midwifery supporters encountered organized, well-funded, and authoritative opposition from the Montana Medical Association, the Montana Nurses’ Association, the Montana Hospital Association, and individual hospitals and physicians. Mona Jamison, lobbyist for the Montana Midwifery Association, explained that midwifery advocates found themselves “against the establishment” and in direct confrontation with the medical profession.

Midwifery Bill proponents countered the influence of health-care providers and institutions by emphasizing the long-standing importance of midwifery throughout Montana history. They also mobilized a large, grassroots support network to communicate with senators and representatives, and a committed group of home birth advocates traveled to the legislature to be present for testimony on the bill. Midwifery supporters drove to Helena during the Montana winter “in storms and caravans of cars” to attend hearings. For each hearing on the Midwifery Bill, supporters “filled the room with mothers and with babies,” demonstrating by sheer numbers the importance of home birth to Montana voters.

Home birth supporters made much of Montana’s geographic isolation and the ability of midwifery to provide adequate medical care to a rural and scattered population. They also provided statistics demonstrating the safety of home birth, and they trumpeted the rights of Montanans to determine the circumstances of their individual birthing experiences.

Despite intense opposition, Montana home birth supporters secured successful passage of the Midwifery Bill, HB 458, with strong legislative approval. Many legislators supported the bill because they believed it provided health-care options to the state’s rural population. Midwifery advocates won the day by focusing on issues specific to Montana—its long history of home birth midwifery, limited rural medical services, and individual choice.

Nevertheless, for midwifery supporters the battle was about a much more fundamental issue: a woman’s right to control her own health-care decisions. According to Jamison, the legislation “was really a reflection of the greater societal view on who’s in charge, and who’s in charge of women’s bodies. So this was . . . a breakthrough on a greater issue than just the issue of home birth.” By exempting home birth midwifery from the Medical Practice Act, legislators endorsed the notion that Montana women should be able to birth at home, and that Montana parents could choose how and where their children would be born. The Montana legislature placed parents in charge of birth, and supported women’s individual birthing preferences.

On April 11, 1989, Montana Gov. Stan Stephens signed the Midwifery Bill into law, guaranteeing Montana midwives an exemption from the Medical Practice Act. During the following session, legislators passed a bill to formally regulate the profession of home birth midwifery. At that time, only ten other states licensed midwives to assist with home deliveries, marking Montana as an early supporter of legalized midwifery.

Hospital and home births have shown comparable success rates for low-risk births since 1989, and Montana women continue to choose midwifery care. The decades since legalization have vindicated the legitimacy of home birth as an option for pregnant women.

Since legalization, Montana midwives have practiced with state sanction, even as women in North and South Dakota, Wyoming, and Idaho could not access legal midwifery care. Idaho legalized home birth midwifery only in 2009 and Wyoming in 2010, while mothers desiring midwifery assistance to deliver at home in North and South Dakota must still do so illegally.

Montana midwives’ fight for licensure created an environment supportive of birth options for Montana women. Montana’s home birth rate topped national rankings in 2009, and continues to surpass national home birth statistics. Early midwifery legalization and sustained home birth practices put Montana midwives at the forefront of the national home birth movement and protected the practice of midwifery in the state. JH

Sources

Browder, Dolly. Interview with Darla Torres, March 4, 2002, Missoula, Montana. OH 378-1, Montana Feminist History Project, Archives and Special Collections, Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula.

Hill, Jennifer J. “Midwives in Montana: Historically Informed Political Activism.” Ph.D. dissertation, Montana State University, 2013.

Jamison, Mona. Interview with Jennifer Hill, October 29, 2012, Helena, Montana. Personal collection of the author.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Births: Final Data for 2009.” National Vital Statistics Reports 60, no. 1 (November 3, 2011).