Born in 1910 as Halley’s Comet streaked by, Inez Ratekin Herrig died ninety-four years later, an exemplary engaged citizen and community champion. For all but two of those years Herrig lived in Libby, Montana; for all but twenty years she occupied her parents’ small art- and music-filled home. In young adulthood, she helped to care for her older brother, who had encephalitis and Parkinson’s. She also helped support her family when her father lost his sight. In 1953, at the age of forty-three, she married Bob Herrig, an educator and forester with deep local roots. In a life framed by duty, social convention, and the economic and geographical confines of her remote northwestern Montana home, Herrig served her community as librarian, engaged volunteer, policy advocate, and local historian.

Herrig’s passion for books and for community service surfaced at age twelve when she began volunteering at Libby’s tiny public library. In 1927, a year out of high school, she took library work in Seattle to fund classes at the University of Washington. Two years later, facing the Depression and her parents’ poverty, she returned home to fill the vacant Lincoln County librarian position, a job she would hold for the next sixty years.

“My idea was to get the right books to the right people at the right time,” Herrig told interviewers often. In the early years, she mailed books to patrons in the county’s remote corners. She established school-library partnerships, organized Montana’s first regional library federation, and oversaw the library’s evolution from the Libby Hotel lobby to its own facility. Of all the recognition she received, later in life she would recall most quickly her library’s national award for service to patrons.

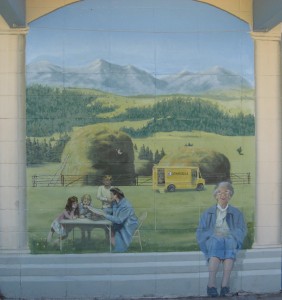

In 1956, she launched the county’s first bookmobile, “an old laundry wagon with shelves.” For twenty years, in steadily improving vehicles, Herrig reached remote Lincoln County locations six times a year, sometimes dodging logging trucks, sometimes navigating deep snow.

Throughout her life, Herrig participated unstintingly in community service. She taught piano lessons, played for the First Presbyterian Church, and volunteered for relief and civic causes sponsored by the Libby Women’s Club. During the 1970s, while still working full-time as county librarian, Herrig helped found the Heritage Museum with her husband and other local history enthusiasts. She served on the museum’s board, gave tours, sought grants, and shared her encyclopedic knowledge of personal and area history.

Herrig had herself, by then, made some of Libby’s most critical history. In 1946, when clear-cut logging, increased U.S. Forest Service presence, and technological changes threatened Libby’s survival, Herrig took action, orchestrating the town’s participation in the Montana Study—a humanities-based research project funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and the University of Montana. Based on Northwestern University professor Baker Brownell’s powerful, romanticized faith in sturdy rural communities, and designed to stabilize rapidly changing small towns, the study offered twelve Montana communities the opportunity to analyze their histories, problems, and strengths to create informed plans of action.

Herrig’s commitment to civic discourse and her love of Libby matched the Study’s framework. As a poised, articulate, single thirty-seven year old, Inez chaired Libby’s weekly Montana Study discussions from January through April 1947. Following the prescribed outline, she offered the library for meetings and kept the group’s discussions civil and productive. In April, the Libby Study Committee published its findings and scheduled a follow-up community meeting. More than fifty local organizations sent representatives. A permanent Greater Libby Association resulted; Herrig served as secretary.

Of the Libby Study Committee’s primary recommendations, the association concentrated most on securing a new hospital and advocating for a sustained-yield agreement between the forest service, private landowners, and logging companies “to promote the stability of forest industries, of employment, of communities, and of taxable wealth.” Such cooperative agreements asked all parties to commit to carefully measured timber harvests to keep the timber industry and towns viable into an indefinite future. Authorized under the 1944 Sustained Yield Management Act, the particulars pertaining to each forest required complex negotiations. Multiple entities in a community—companies, unions, governments, and citizens—had to compromise and trust. Herrig believed that was possible—especially because, as a girl, she’d witnessed the civic-minded J. Neils Lumber Company’s tangible commitment to Libby and its citizens.

Herrig’s ultimately misplaced optimism about a local agreement reflected her belief in civic dialogue and fueled her leadership in discussions. But the Greater Libby Association proved far more successful in raising money for a new hospital, improving city streets, and creating teenage-friendly Halloween celebrations than in securing the complicated sustained-yield agreement.

In 1995, Herrig spoke to a Libby High School Principles of Democracy class as they worked to replicate the Montana Study. “Libby is having growing pains,” she said. “And we can’t pursue future goals until we discuss them as a community. . . . All I can say is listen to one another. Find out why you disagree . . . and what you want for your community.”

Circumstances—including a late and childless marriage—gave Herrig the opportunity to craft a professional and civic life richer than many Montana women experienced. She turned those circumstances into uncommonly powerful tools on behalf of her community. The Montana Study minutes from February 25, 1947, best summed up her life: “Miss Ratekin [Herrig] considers it a personal obligation to develop the best that is in us and use one’s talents to help make the community better.” MSW

Inez Herrig was just one of many Montana women involved in library work. Read more about the role women’s groups played in forming libraries in “Progressive Reform and Women’s Advocacy for Public Libraries in Montana.”

For stories of individual librarians, see “Laura Howey, the Montana Historical Society, and Sex Discrimination in Early-Twentieth-Century Montana” and “Alma Smith Jacobs: Beloved Librarian, Tireless Activist.”

Sources

“Beloved Librarian Dies at 94.” The Western Montana News [Libby], December 29, 2004.

Herrig, Bob, and Inez Herrig. Interviewed by Victor Bjornberg and Jennifer Jeffries Thompson, Montana Historical Society Oral History 152, April 24, 1980, Libby.

Herrig, Inez. Interviewed by Jodie Foley, Montana Historical Society Oral History 2001, May 21, 2002, Libby.

Homstad, Carla. “Small Town Eden: The Montana Study.” University of Montana M.A. thesis, July 1987.

Leimbach, Lydia Beth. “Inez Ratekin Herrig.” In Women of Montana: Essays, 1986-1990, edited by Diane Sands. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Moving Press, 1990.

The Montana Study Research Collection. Montana Historical Society, MC 270, 1943-1954.

Morris, Roger, ed. “Citizen Herrig.” The Western Montana News. December 29, 2004.

Poston, Richard Waverly. Small Town Renaissance: A Story of the Montana Study. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1950.

White, Mark. “Inez Herrig Provided Vital Connection to County History.” The Western Montana News [Libby]. December 31, 2004.