When the U.S. Senate approved the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in March 1972, the next step—passage by two-thirds of state legislatures—seemed a formality. However, over the next decade, the battle over ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment revealed that America was still divided over equality between the sexes. In Montana the controversy over the ERA suggests equal unease.

The Equal Rights Amendment read simply, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” First proposed in 1923, the amendment passed out of Congress in 1972. It then went to the states for approval. In theory, Montana’s ratification should have been easy; the state constitution, recently passed in 1972, included an “individual dignity” clause that already guaranteed Montana women equal rights. In fact, ERA proponents argued that ratification was a way for Montanans to ensure that “their loved ones in other states . . . enjoy the same benefits and protections which we have under our state laws.”

In reality, ratification was controversial from the beginning. The amendment “breezed through the House by a 73-23 vote” in 1973, but, despite the fact that forty out of Montana’s fifty state senators had signed on as sponsors of the bill, anti-ERA activists managed to convince the Senate to table discussion.

The topic proved “emotionally explosive” when ratification came up again in 1974. According to the Billings Gazette, “the Equal Rights Amendment has triggered more public response than any other issue before the legislature.” In a debate published in the Kalispell Daily Inter Lake, Elizabeth McNamer, wife of a senator who had led the fight against the ERA the previous year, averred that while she was “all for women’s rights” she opposed the amendment because it would “strip all women of certain legal benefits in order to give some women needed rights.” She also appealed to traditional arguments about women’s role in society: “Women are the gentler sex. . . . We are the civilizers. Women are better at raising children. I speak from personal experience. My mother, the original women’s libber, worked and my father stayed at home. It doesn’t work.” Supporters of ratification claimed the “argument . . . that the Equal Rights Amendment would destroy home life and force women into servitude . . . is preposterous,” but McNamer’s statement reflected a widely expressed fear that women would lose their “privileged” position in society if ERA passed.

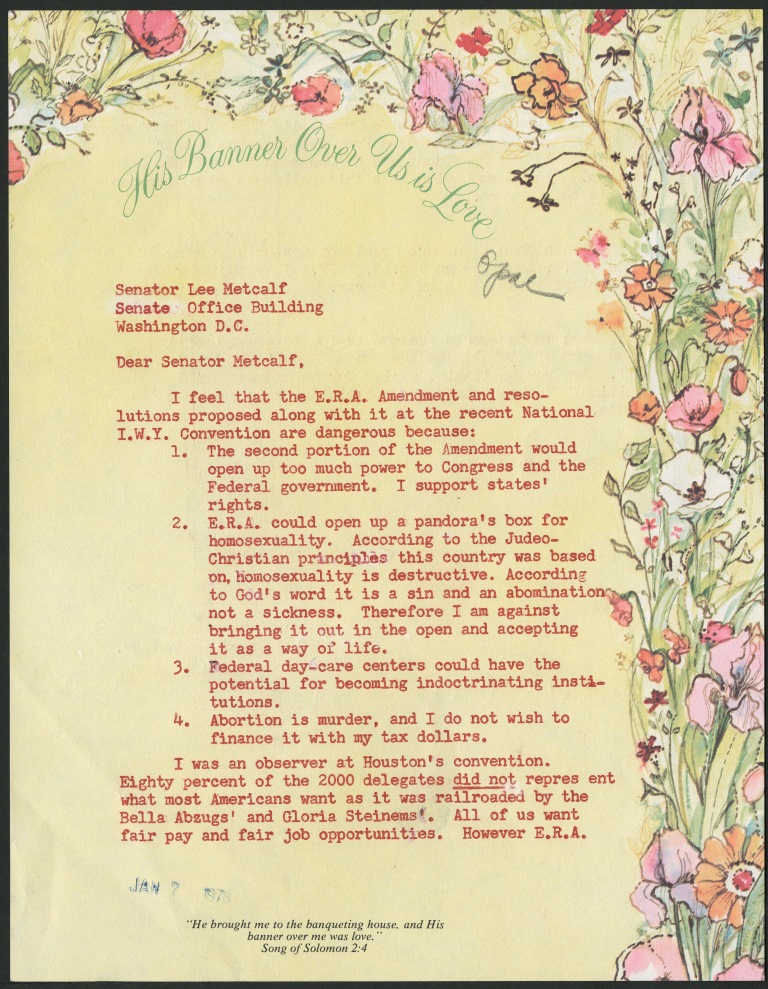

Amid heated debate, ratification ultimately eked through the Senate in 1974, making Montana the thirty-second state to approve ERA. The controversy, however, did not die with ratification. Passage of the amendment required ratification by thirty-eight states, and by 1974 the amendment’s political momentum had stalled. A coalition of social conservatives and religious institutions mounted a well-organized and highly visible campaign against the amendment. Groups like Phyllis Schlafly’s Stop ERA mobilized members to oppose ratification in states considering ERA and to fight for rescission in states that had already ratified.

In Montana, a group calling itself Montana Citizens to Rescind ERA organized almost immediately after ratification. Marcella Warila of Butte joined the club because she wanted “to keep our right to stay home and be homemakers.” Anti-ERA advocates also appealed to fears that the amendment would promote homosexuality, facilitate on-demand abortions, lead to unisex bathrooms, and make women subject to military conscription. After the Montana Supreme Court struck down Rescind ERA’s attempt to bring the issue to Montana voters in a 1974 referendum, they instead focused on lobbying the Montana legislature, and bills to rescind were introduced in the 1975, 1977, and 1979 sessions.

The issue was especially heated in 1979. The previous year Congress had voted to extend the deadline for ratification from March 1979 to June 1982, to give ERA supporters more time to get the amendment through recalcitrant state legislatures. By the time Montana’s 1979 legislature convened, three states—Idaho, Nebraska, and Tennessee—had already rescinded, and one state—South Dakota—had stipulated that its ratification would end with the original 1979 deadline.

Montana conservatives decided to follow South Dakota’s lead. Backed by Betty Babcock, the former first lady and 1972 constitutional convention delegate, and Patrick Sherrill, a lobbyist sent by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Senator Jack Galt introduced a resolution affirming the March 1979 deadline. While Galt claimed that the resolution was simply meant to “reaffirm Montana’s respect for the Constitution and the time-tested process of amending it,” ERA proponents argued that the resolution was “cheap rescission.” Hundreds of people came to the committee hearing on the resolution, which “squeaked through” the Senate by a vote of 26-24 but ultimately died in the House.

In the end, Montana’s ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment stood, suggesting that Montanans had an ideological commitment—albeit an uneasy one—to gender equality. Ultimately, however, the debate was moot. No states ratified the ERA after 1977, leaving the amendment stalled three states short of the thirty-eight needed for ratification. Speaking in March 1982, when defeat of the amendment seemed inevitable, ERA proponent and state legislator Dorothy Bradley encouraged her audience to focus on all that they had accomplished. “If it hadn’t been for the nationwide ERA campaign,” she argued, “it is unlikely Montana would have created its own Constitutional provision for equal rights.” “We probably won’t have the ERA on June 30,” she continued, “but look around yourself and you know our work will leave a mark. . . . [T]he efforts on behalf of equal rights, and on behalf of women, will continue.” AH

Doris Brander, pictured above at a rally supporting ERA, led the campaign in Montana to recognize women veterans for their military service. Read about Doris Brander and the Fight To Honor Women’s Military Service in an earlier post in this series.

Sources

Bradley, Dorothy. “Equal Rights–Where from Here.” Address to the Equal Rights Council, March 6, 1982. Copy in folder ERA Ongoing, box 1, Frances Elge Papers, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Clark, Phyllis. “Equal Rights Amendment Is Not ‘Women’s Lib.’” Daily Inter Lake [Kalispell], January 23, 1974, 4.

Clawson, Roger. “Friends, Foes Debate ERA.” Billings Gazette, January 25, 1974, 12.

Constitution of the State of Montana, copy online at courts.mt.gov/content/library/docs/72constit.pdf.

Cook, Kathleen. “Equal Rights Proponent Says: ‘Sometimes Majority Is Wrong.’” Montana Standard [Butte], Septeber 15, 1974, 26.

_______. “Why Fight Equal Rights?” Montana Standard [Butte], September 8, 1974, 18.

Elkin, Larry. “ERA and Constitution in a Timely Fight.” Independent Record [Helena], February 8, 1979. Copy in folder ERA, box 1, Frances Elge Papers, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

“ERA Outcome Is Praised.” Independent Record [Helena], March 13, 1979, 9.

Frances Elge Vertical File, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Frances C. Elge Papers, 1921-1991, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Jepsen, Rev. Gary. “ERA Stand is Explained.” Independent Record [Helena], February 19, 1979. Copy in folder ERA, box 1, Frances Elge Papers, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Moes, Garry. “House Kills Montana ERA Nullification.” Independent Record [Helena], March 11, 1979, 12. Copy in folder ERA, box 1, Frances Elge Papers, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Montana Equal Rights Council. “Montana and the Equal Rights Amendment” [n.d., after 1978]. Folder ERA 1972, Box 1, Frances Elge Papers, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. In Pursuit of Equity: Women, Men, and the Quest for Economic Citizenship in 20th Century America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

“The National Countdown on ERA.” Independent Record [Helena], March 11, 1979, 12. Copy in folder ERA, box 1, Frances Elge Papers, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Quinn, D. Michael. “The LDS Church’s Campaign against the Equal Rights Amendment.” Journal of Mormon History 20, no. 2 (Fall 1994), 85-155.

Rosenfeld, Steven P. “Era May Go to the People.” Billings Gazette, January 11, 1974, 1.

Rygg, Brian. “Making a Mockery of Equality.” Great Falls Tribune, March 12, 1979. Copy in folder ERA, box 1, Frances Elge Papers, Montana Historical Research Center, Helena.

“Senate Faces ERA, Gambling Bills.” Daily Inter Lake [Kalispell], January, 14, 1974, 2.

Sherrill, Patrick. “Defends Stance on ERA.” Independent Record [Helena], March 12, 1979, 4. Copy in folder ERA, box 1, Frances Elge Papers, Montana Historical Research Center, Helena.

Soule, Sarah, and Brayden G. King. “The Stages of the Policy Process and the Equal Rights Amendment, 1972-1982.” American Journal of Sociology 111, no. 6 (May 2006), 1871-1909.