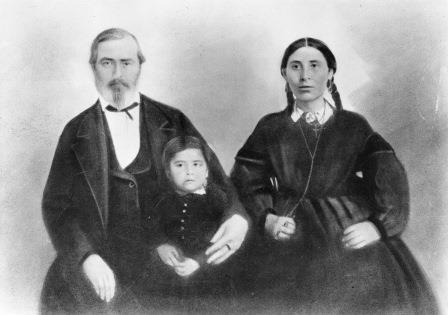

In 1844, influential Piegan warrior Under Bull and his wife, Black Bear, chose American Fur Company clerk Malcolm Clarke to be their teenage daughter Coth-co-co-na’s husband. During their twenty-five year marriage, Coth-co-co-na bore two boys and two girls, moved briefly with Clarke to Michigan, and helped him establish a ranch near Helena. She mourned deeply when Clarke sent their two oldest children east for schooling. In 1862, she accepted Clarke’s new mixed-blood wife, Good Singing, into their home. According to her children’s accounts, her husband’s murder in 1869 left Coth-co-co-na a broken woman. She died in 1895.

For two centuries—from the mid-1600s to the 1860s—Indian and Métis women like Coth-co-co-na brokered culture, language, trade goods, and power on the Canadian and American fur-trade frontier. They were partners, liaisons, and wives to the French, Scottish, Canadian, and American men who scoured the West for salable furs. Stereotyped by early historians as victims or heroines (and there were both), indigenous women also wielded significant, traceable power in this era of changing alliances, increasing intertribal conflict, and expanding European presence in the West.

The roles indigenous women played during the fur trade reflected the roles they historically held within their communities. Despite cultural distinctions among tribes, indigenous women generally shared the common responsibilities of procuring and trading food, hides, and clothing. Women also embodied political diplomacy as tribes forged internal and intertribal relationships around family alliances and cemented these social structures through (often polygamous) marriage. These traditional economic and political roles placed indigenous women at the center of trade, and made them desirable and necessary partners for fur traders.

A multicultural and economically diverse group working for international companies, the fur traders who came to Montana were all far from their families. Whether company managers, clerks, laborers, or trappers, the men sought companionship, intimacy, and entrée into local tribal communities, as well as assistance in making their economic endeavors a success. Marriage to indigenous women could provide all of these things.

In keeping with tribal customs, traders arranged liaisons with indigenous women by exchanging gifts with tribal families, who themselves recognized the potential benefits of establishing alliances. Depending on both partners’ preferences, relationships lasted a season, many months or years, or a lifetime. Some indigenous wives returned to eastern settlements with their white husbands; some raised families together in the West.

Whatever the specifics of their individual relationships, the important socioeconomic positions indigenous women held in their own cultures manifested in their contributions to the fur trade. Indigenous wives gave fur traders invaluable ties to the land and tribes. Their knowledge of the region’s climate, wildlife, plants, languages, and topography shortened considerably the male outsiders’ learning curves. At the same time, the women brought inside information to their tribes about the reliability of traders and prices while relaying tribal news to their white partners.

Indigenous women also accomplished work fundamental to the survival of the fur traders and to their economic success. While incorporating European household goods into their daily lives (and thus making those goods more marketable), women in the fur trade continued to utilize indigenous methods to produce food and durable goods such as clothing, footwear, and blankets as well as baskets, parfleches, and other portable trade and traveling containers. Women also prepared hides, expertly cleaning and tanning them to command high prices.

Notwithstanding the power they derived from being experienced locals, many indigenous wives faced adversity and tragedy. They had to learn new languages, navigate European cultural norms, and often adapt to unfamiliar dwellings. Separation from their families and the reality of living amid an almost exclusively male population caused particular hardship; fur trade wives lost the support and companionship of other women with whom, in their native societies, they would have shared the duties of daily work and child rearing. Living at fur forts also placed them at increased risk of sexual exploitation. In addition, close proximity to Europeans exposed indigenous women to many infectious diseases. In 1837, when a steamboat brought smallpox up the Missouri, they were among the disease’s first victims—and its first carriers back to tribes.

As missionaries, gold miners, and their families increasingly brought the strictures of Christianity and racial hierarchies to the West, indigenous wives faced greater prejudice. Montana pioneer Granville Stuart’s change of heart toward Awbonnie, his Shoshone wife of twenty-six years and the mother of his eleven children, illustrates the new quicksands. When Awbonnie died in 1888, Stuart prepared a funeral card that read, “And now may the birds sing above her . . . noble, devoted, self-sacrificing wife and gentle and loving mother, farewell.” Still, within a year, Stuart had remarried a white woman and begun formally excluding his mixed-blood children from his life.

The feelings and perceptions of women like Awbonnie and Coth-co-co-na, who brokered the geographical and cultural frontiers of the North American continent’s fur trade, do not exist in written documents. Most of what we know of their lives comes from traders and territorial visitors, not the women themselves. Thus, we know from a visitor’s published account that Coth-co-co-na adorned her husband with her artistry, gifting him with a beautifully beaded tobacco sack. But we don’t know how she felt about her husband or her role as the indigenous wife of a Euro-American. Nevertheless, careful reading of existing documents can reveal glimpses of the complexities that she and other indigenous women faced as they melded their lives with men from a very foreign culture. MSW

The Métis are often called “children of the fur trade.” Read about Cecilia Wiseman’s experience growing up Métis in the twentieth century in “A Métis Girlhood.”

Looking for more about the Métis in Montana? Check out this Bibliography of Resources about Native American and Métis Women in Montana.

Sources

Boller, Henry A. Among the Indians: Eight Years in the Far West, 1858-1866. Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1959 (1868).

Brown, Jennifer S. H. Strangers in the Blood: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1980.

Graybill, Andrew. The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West. New York: W. W. Norton, 2013.

Lansing, Michael. “Plains Indian Women and Interracial Marriage in the Upper Missouri Trade, 1804-1868.” The Western Historical Quarterly 31, no. 4 (Winter, 2000), 413-33.

Meikle, Lyndel, ed. Very Close to Trouble: The Johnny Grant Memoir. Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1996.

Milner, Clyde II, and Carol O’Connor. As Big as the West: The Pioneer Life of Granville Stuart. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Schemm, Mildred Walker. “The Major’s Lady: Natawista.” The Montana Magazine of History 2, no. 1 (January 1952), 4-15.

Van Kirk, Sylvia. Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur-Trade Society, 1670-1870. Winnipeg: Watson & Dwyer, 1980.

Wischmann, Lesley. Frontier Diplomats: Alexander Culbertson and Natoyist-Siksina among the Blackfeet. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.