Across the frontier West, abandonment, poverty, domestic abuse, and poor education led some women to crime. When women stood accused of serious crimes in all-male courtrooms, gender, race, and social status worked against them. And, once incarcerated, women served their time neglected and forgotten in prisons built for men. The Montana Territorial Penitentiary at Deer Lodge, built in 1871, was no exception.

In 1878, Hispanic prostitute Felicita Sanchez became the first female inmate at Montana’s prison. True to form, her ethnicity, profession, and gender were factors in her three-year sentence for manslaughter. As the warden led her to an empty cell within the men’s cell house, three guards refused to attend a female prisoner and resigned.

A year later, Mary Angeline Drouillard was the second woman sentenced to Deer Lodge. Drouillard sat in the Missoula County jail for a year, awaiting trial for the shooting death of her abusive husband. At twenty-four, she was three times married and twice divorced, a battered woman whose multiple partners implied loose morals. These factors and her French Canadian heritage guaranteed conviction. Although Mary’s young daughter had witnessed the crime and could have corroborated her mother’s story, no one questioned her, and the judge sentenced Drouillard to fifteen years in the penitentiary.

Nineteenth-century society saw Sanchez and Drouillard as fallen women, whose ethnicity and sexual conduct made them unredeemable. Guilt or innocence hardly mattered in courtrooms where all-male juries often based their verdicts on social bias. Jury demographics changed little in the early twentieth century, even after Montana women won suffrage in 1914. Women began serving on juries only after the state legislature redefined the term “jury” as a “body of persons” instead of “a body of men” in 1939.

Wealthy Missoula madam Mary Gleim was one of the few who beat the system. Charged with dynamiting the home of a rival, she was convicted of assault with intent to commit murder. She began her fourteen-year sentence in 1894, but expensive attorneys won her a new trial. Witnesses disappeared, the victim died, and the judge dismissed her case. Before year’s end, Mary Gleim paid her bond and walked out of prison.

Bessie Fisher was not so lucky in 1901. When “Big Eva” Frye drew a knife and lunged at her, Fisher fired her gun. The coroner ruled it self-defense. But because she was black, addicted to morphine, and a common prostitute, nineteen-year-old Fisher had three strikes against her. The jury found Fisher guilty, and the judge sentenced her to twenty years at Deer Lodge.

Deer Lodge was a men’s prison, where female inmates were never allowed to leave their cells. Believing that hard work rehabilitated prisoners, Warden Frank Conley put his convicts to work building a massive wall, a cell house, an exercise yard, and female quarters. Conley’s work ethic, however, did not include women. Confined inside the men’s domain, women languished in their cells.

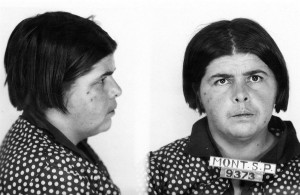

In 1908 women inmates moved to their own small facility but women could access their own enclosure only through the men’s yard. A female matron replaced male guards, but still, women had no educational or work opportunities. In 1910, the state’s three female inmates—including Bessie Fisher—were afterthoughts of the judicial system.

In 1918 half of all prisoners at Deer Lodge were listed as “mentally insane.” Edith Colby of Thompson Falls was one of them. An aspiring newspaperwoman in 1916, Colby traded insults with a local politician before shooting him three times. Throughout the trial, Colby maintained that her editor had taught her to shoot a gun and had encouraged her to use it. Burton K. Wheeler of Butte viciously prosecuted the case. Defense attorneys tried to prove insanity, but the jury found her guilty, and Colby served three years in prison.

Lucy Cornforth’s pathetic case came before a Miles City judge in 1929. Contemplating suicide, Cornforth had purchased strychnine, mixed it in a cup, and told her eight-year-old daughter of her plans. But Cornforth changed her mind and set the cup aside. The child cried out, “I want to go too!” She seized the cup, drank the poison, and died minutes later.

Cornforth pled guilty to first-degree, premeditated murder. Her attorney argued that she was “intellectually deficient,” and the judge agreed to life in prison instead of the death penalty. Cornforth was a model prisoner, and after she had served fifteen years, a sponsor agreed to employ her in his home. However, the judge refused parole, maintaining that Cornforth still posed a threat to herself and society. Ten years later, in 1954, a retired teacher again requested a parole board’s review for Cornforth, but to no avail.

In 1959, a prison riot and an earthquake forced the state to remove women inmates from Deer Lodge. For the next thirty-five years, officials shuffled them from one makeshift facility to another until, in 1994, a retrofitted treatment center in Billings became the women’s prison. It currently accommodates more than 265 inmates.

When Bessie Fisher did her time in the early years of the twentieth century, African Americans were the largest minority among Montana women inmates. This figure is astounding given that black women were so few in Montana in 1910 (only 776 out of Montana’s 149,181 female population). Today, a different minority group makes up the majority of women inmates. Only six percent of Montana’s population is Native American, but Indians make up twenty-seven percent of the state’s women inmates.

Although positive changes separate Bessie Fisher’s experiences from those of today’s prisoners, there is need for improvement. Gender, ethnicity, and poverty are controlling issues behind incarceration, and mental illness and abuse are still common threads. Until there are better solutions, incarcerated women will remain afterthoughts of the judicial system. EB

To learn more about women and crime, check out these other blog entries: Montana’s Whiskey Women: Female Bootleggers During Prohibition and Red-Light Women of Wide-Open Butte.

Want to learn more? Read Ellen Baumler’s article, “Justice as an Afterthought: Women and the Montana Prison System,” published in Montana The Magazine of Western History 58, no. 2 (Summer 2008). You can find links to full text of all Montana The Magazine of Western History articles relating to women’s history here.

Sources

Baumler, Ellen. “Justice as an Afterthought: Women and the Montana Prison System.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 58, no. 2 (Summer, 2008): 41-59, 97-99.

—, and J. M. Cooper. Dark Spaces: Montana’s Historic Penitentiary at Deer Lodge. Santa Fe: University of New Mexico, 2008.

Butler, Anne. Gendered Justice in the American West: Women Prisoners in Men’s Penitentiaries. Urbana: University of Illinois, 1997.

Byorth, Susan. “History of Women Inmates: A Report for the Criminal Justice and Corrections Advisory Council,” 1989, at http://www.cor.mt.gov/content/About/HistoryofWomenInmates.

Montana State Prison Convict Records. State Microfilm 36. Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.