Dorothy M. Johnson was Montana’s most successful writer of Western fiction. Born in Iowa in 1905, Johnson grew up in Whitefish, Montana. Her love of the West and nineteenth-century frontier history and folklore inspired her to write seventeen books, more than fifty short stories, and myriad magazine articles. On the basis of her publishing success and numerous awards, scholars Sue Mathews and Jim Healey have called Johnson the “dean of women writers of Western fiction.”

Johnson’s family moved to Montana in 1909 and settled in Whitefish in 1913. She graduated from Whitefish High School in 1922 and studied premed at Montana State College (Bozeman) before transferring to Montana State University in Missoula. By the time she graduated with a degree in English in 1928, she had already published her first poem.

After college, Johnson left Montana and worked as an editor in New York for several years. In 1950, she returned to Montana and became editor of the Whitefish Pilot. Three years later, she relocated to Missoula to teach at the university and work for the Montana Press Association. She lived in Missoula until her death in 1983.

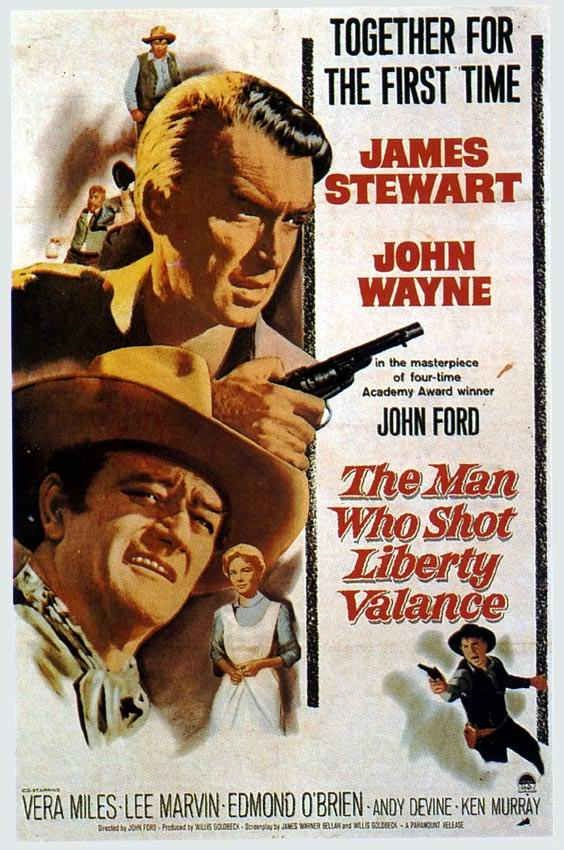

Ironically, many people who might not know Johnson’s name are, nevertheless, familiar with her work. Three of her stories—“The Hanging Tree,” “A Man Called Horse,” and “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”—were made into motion pictures. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a 1949 John Ford film starring Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne, has the honor of being listed on the National Film Registry for its cultural significance to American cinema. Johnson recalled that she conceived of the story while questioning the western myth of manly bravado: “I asked myself, what if one of these big bold gunmen who are having the traditional walkdown is not fearless, and what if he can’t even shoot. Then what have you got?”

Johnson’s work modifies the formula of the strong, stoic western male. In her work, Westerners (both male and female) are tough but not invincible. Speaking of the real Westerners who inspired her characters, Johnson explained: “I think the people who headed West were a different kind of people. Somebody said in a long poem that the cowards never started and the weaklings fell by the way. That doesn’t mean that everyone who went West was noble, brave, courageous, and admirable because some of them were utter skunks, but they were strong, and I like strong people.”

Johnson focused on women’s stories as well as men’s. Women in Johnson’s stories tend to be strong and loyal. Scholar Sue Hart notes that love and sacrifice are common themes in Johnson’s work: “‘I believe in love,’ Johnson says—and her finest characters reflect that belief.” Johnson also attempted to incorporate the perspectives of Indian women. Her novel Buffalo Woman focuses on the story of Whirlwind, an Oglala Sioux woman living in the aftermath of the Battle of Little Bighorn. Johnson considered Buffalo Woman to be one of her best books, and the National Cowboy Hall of Fame honored the work with its prestigious Western Heritage Award.

In her later life Johnson published several articles about her childhood in Montana The Magazine of Western History. Her nonfiction expresses her love of Montana and her sense of the West’s meaning. She described Whitefish as a “raw new town,” filled with opportunity thanks to the jobs created by the Great Northern Railroad. For the workers drawn to Whitefish, it was “the anteroom of paradise . . . the promised land, flowing with milk and honey. All they had to do to enjoy it was work.”

The hardworking men and women of Whitefish stood in contrast to the “rich people and Eastern dudes” she encountered in Glacier National Park. Interestingly, when she wrote of the social stratification she noticed among visitors to the park, she framed it in terms of an East-West divide: “We unrich Westerners were suspicious of the whole lot of them. We looked down on them because we thought they looked down on us. But they didn’t even see us, which made the situation even more irritating. Years later, when I lived in a big Eastern city, I learned not to see strangers. . . . But in the uncrowded West, in my country, it’s bad manners, and on the trail it’s proper to acknowledge the existence of other human beings and say hello.”

Above all, Johnson was a consummate Westerner, and this helped her excel in a literary genre that tended to be associated with men. Johnson defended women’s ability to write Westerns: “After all, men who write about the Frontier West weren’t there either. We all get our historical background material from the same printed sources. An inclination to write about the frontier is not a sex-linked characteristic, like hair on the chest.” Though Johnson never grew hair on her chest she was, according to one friend, a “witty, gritty little bobcat of a woman,” and her writings reflect her western spirit. AH

Read Dorothy Johnson’s charming reminiscences about growing up in Whitefish, published in Montana The Magazine of Western History. (Scroll down the page to access.)

Sources

“Dorothy Johnson, Author of ‘Liberty Valance,’ Is Dead.” New York Times, November 13, 1984. Available online at http://www.nytimes.com/1984/11/13/obituaries/dorothy-m-johnson-author-of-liberty-valance-is-dead.html. Accessed March 13, 2014.

“An Editorial Forethought.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 24, no. 3 (Summer 1974), 80.

Great Falls Tribune staff. “Dorothy Johnson.” 125 Montana Newsmakers. Available online at http://www.greatfallstribune.com/multimedia/125newsmakers3/johnson.html. Accessed March 13, 2014.

Hart, Sue. “Dorothy M. Johnson: A Woman’s Voice on the Western Frontier.” The English Journal 74, no. 3 (March 1985), 60-61.

Hintze, Lynnette. “Influential Whitefish Author Dorothy Johnson Inducted into Gallery of Outstanding Montanans.” Kalispell Daily Interlake, March 13, 2005. Available online at http://www.dailyinterlake.com/community/lifestyle/article_49988198-43d2-52fa-896c-a933dd41a320.html. Accessed March 13, 2014.

Johnson, Dorothy M. “Carefree Youth & Dudes in Glacier.” Montana The Magazine of Western History, 25, no. 3 (Winter 1975): 48-59.

_____________. “The Foreigners.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 26, no. 3 (Winter 1976), 62-67.

_____________. Letter to the Editor. Montana The Magazine of Western History 23, no. 3 (Summer 1973), 61.

_____________. “The Safe and Easy Way to Adventure.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 24, no. 3 (Summer 1974), 80-87.

_____________. “A Short Moral Essay for Boys and Girls: Or How to Get Rich in a Frontier Town.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 24, no. 1 (Winter 1974), 26-35.

Mathews, Sue, and James W. Healey. “Winning of the Western Fiction Market: An Interview with Dorothy M. Johnson.” Prairie Schooner 52, no. 2 (Summer 1978), 158-67.

“National Film Registry 2007.” http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/08012/registry.html. Accessed February 27, 2014.