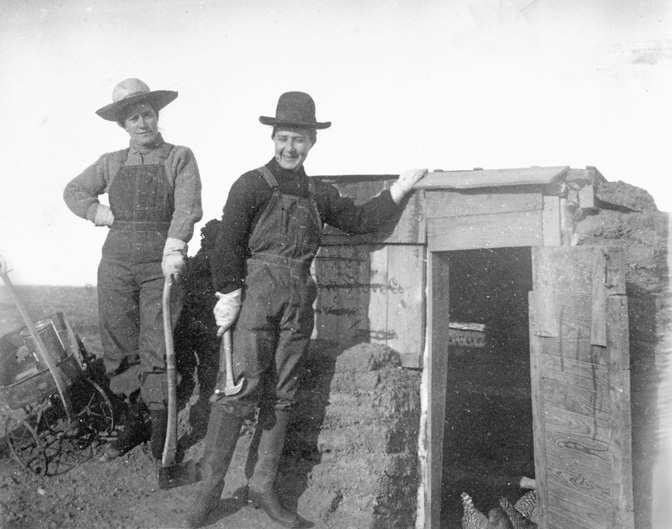

Historians estimate that up to 18 percent of homesteaders in Montana were unmarried women. Passage of the Homestead Act of 1862 allowed any twenty-one-year-old head of household the right to homestead federal land. Single, widowed, and divorced women fit this description, and they crossed the country to file homestead claims of 160 acres. After the turn of the century, when the Enlarged Homestead Act doubled the acreage to 320, even more women took up free land in Montana. While not all succeeded, those who did proved that women were up to the task. Gwenllian Evans was Montana’s first female homesteader. A widow from Wales, she emigrated to the United States in 1868. Her son, Morgan Evans, was Marcus Daly’s land agent and a well-known Deer Lodge valley rancher. In 1870, Gwenllian Evans filed on land that later became the town of Opportunity; she received her patent in 1872. She was one of the territory’s first post mistresses and lived on her homestead until her death in 1892.

The Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909 marked the beginning of Montana’s homesteading boom in earnest, and brought many more single women to Montana. Women, like men, homesteaded for a variety of reasons and did not always intend to stay. Grace Binks, Ina Dana, and Margaret Majors homesteaded together in the Sumatra area in Rosebud County in 1911. The three women from Ottumwa, Iowa, along with Dana’s mother, came for the adventure. They claimed land, used each other as witnesses for final proof of occupancy, and then commuted their patents by buying their properties. Dana and Binks each paid $200 for their land titles. All three women left their claims after a year. A photo album documents the pride they felt in their accomplishments on the land, details the homes they made, and the neighbors they enjoyed.

Some women homesteaded in partnership with other family members to accumulate large holdings. The Scherlie family claimed land in a desolate area in Blaine County called the Big Flat. Thirty-two-year-old Anna Scherlie filed in 1913 on land adjacent to two of her brothers’ claims and three of her sisters’. At that time, women made up about one-fourth of the total homestead applicants in the four surrounding townships.

By 1916, Anna Scherlie had forty acres planted in wheat, oats, and flax. Isolation on the Big Flat led many settlers to winter elsewhere, and Scherlie was no exception. Legend has it that during the winters she went to St. Paul to work for the family of railroad magnate James J. Hill. Over the decades, Scherlie made few changes to her small, wood-frame shack, adding only a vestibule she used as a summer kitchen, storage shed, and laundry. She remained in that shack on her land until 1968.

Many homesteading women came to Montana from Canada, where single women could not claim land until the 1930s. They often filed on claims in Montana, but continued to work in Canada while they proved up. One of these independent women was teacher Laura Etta Smalley, who arrived from Edmonton, Alberta, in 1910. Smalley had a meticulous plan, and luck was with her all the way. Over the long Easter weekend, Smalley packed her bag and boarded the train for Inverness, Montana. She arrived in the middle of the night. The hotel was under construction, but the clerk rented her an unfinished room. The next morning, the land locator took her out to view available claims. Smalley found the land she wanted and took the night train to Havre to file. Because it was not safe for single women to travel alone, the locator’s secretary kindly accompanied her. Smalley arrived at the Havre land office on April 1, 1910, the first day a person could file under the new Enlarged Homestead Act. She was the first in line. Within two minutes, many other landseekers were in line behind her. Smalley returned to Canada, finished out the school year, and then returned to Montana. In Havre, she bought a ready-made shack and filled it with furniture and supplies. Men then transported the shack on two wagons twenty-six miles out to her claim and dropped her off. That fall, Smalley returned to teach in Edmonton, but by the opening of the 1911-1912 school year, she had secured a teaching position in Inverness.

In 1914, Laura Smalley married Will Bangs. Smalley moved to her husband’s homestead, but kept her own. And that was good thing, since Bangs lost his farm in 1926. The family, which then included four children, moved to Smalley’s tiny claim shack and their home grew around it. Laura Smalley Bangs died at eighty-seven in 1973, before she could see her grandson work the land she claimed.

These and other women take their place alongside their male counterparts who came to Montana for the opportunities the land offered. Like their counterparts, not all of them succeeded. But those who stayed, and prospered with their land, like Gwenllian Evans, Anna Scherlie, and Laura Smalley Bangs, made significant contributions to Montana’s agricultural history. EB

For more on rural Montana women, see these articles on ranchwoman Nannie Alderson and post-World War II home demonstration clubs.

The Scherlie Homestead is featured on the WHM Places page!

Sources

Bangs Farm, Centennial Farm and Ranch Program. Montana History Wiki at http://montanahistorywiki.pbworks.com/w/page/40438395/Bangs%20Farm.

Baumler. Ellen. “Celestia Alice Earp.” In Ellen Baumler, Beyond Spirit Tailings: Montana’s Mysteries, Ghosts and Haunted Places, 65-68. Helena: Montana Historical Society, 2005.

Carter, Sarah. Montana Women Homesteaders: A Field of One’s Own. Helena: Farcountry Press, 2009.

Cederburg, Leon, and Nellie Cederburg. Anna Scherlie Homestead Shack, National Register of Historic Places Nomination, Montana State Historic Preservation Office, Helena.