Frieda and Belle Fligelman were born in Helena in 1890 and 1891, respectively. Their parents taught them the value of education, the importance of civic engagement, and the necessity of being reasonable. In the Fligelmans’ Jewish household, “God was the idea of goodness,” and being reasonable was inextricably linked to being a good person. On that premise, the Fligelman sisters became dedicated global citizens, actively participating in important twentieth-century social movements as part of their lifelong commitment “to do something good for the world.”

That quest began in 1907, when Frieda persuaded her father to send her, and later Belle, to college rather than finishing school. Articulate, bright, and principled, both sisters excelled at the University of Wisconsin, coming of age during the Progressive Era’s struggles for political, economic, and social equality. After graduating in 1910, Frieda joined the activists marching for women’s suffrage in New York. Back on campus, Belle was elected president of the Women’s Student Government Association and, as an editor for the student newspaper, championed progressive causes. During her senior year, she lobbied the Wisconsin legislature in favor of granting women the vote.

In 1914, Belle returned to Helena to write for the Independent and to promote women’s suffrage. Stumping on street corners and traveling unchaperoned across Montana, Belle startled her audience—and her parents—with her bold, “unladylike” determination to fight for her ideals. After covering Jeannette Rankin’s political campaign for the newspaper, Belle helped elect Rankin to Congress in 1916, and then went to Washington, D.C., as the congresswoman’s secretary. Over the next two years, Belle observed that male leaders seldom addressed the needs of women and children. These needs—such as equal rights, equal pay, and peace—became her lifelong cause.

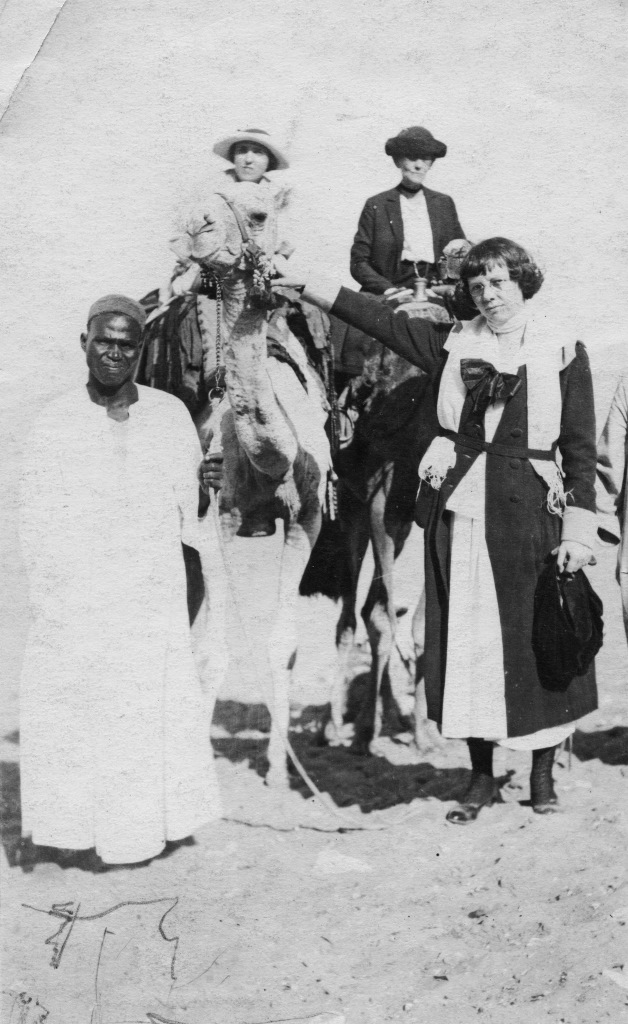

Meanwhile, Frieda enrolled in graduate school at Columbia University, where she studied under pioneering anthropologist Franz Boas. She earned a fellowship to study abroad for several years and focused her research on disproving the theories of racial hierarchies posited by Boas’s rival, Lévy-Bruhl. Frieda, who was fluent in several languages, conducted a comprehensive study of the West African language Fulani, organizing it into categories of social significance in order to demonstrate that Fulani society, as exhibited in language, was as complex and sophisticated as any European society. When Frieda presented her research to the new chair of sociology at Columbia, he refused to acknowledge her work as legitimate sociology and denied Frieda her doctoral degree.

The dismissal of her research (arguably because she was a woman charting new academic territory) deprived Frieda of the opportunity to teach and to conduct research at the university level. Although European institutions published several of Frieda’s scholarly works, she was unable to achieve her dream of working among her intellectual peers to advance innovative investigations into the sociological problems of her era.

Navigating a largely unfulfilling professional life during the 1930s and 1940s, Frieda also agonized over never having found a lifelong companion. She channeled these disappointments into writing, composing over thirteen hundred poems and transforming her heartache into hope:

She had made of her loneliness

So great an art

That now its hurt became a melody

And she was lost in wonder. . .

Forever a champion for the downtrodden, Frieda persevered. She returned to Helena in 1948 and established a one-woman think tank, the Institute for Social Logic. Using “social logic” to evaluate the preconceptions underlying public policies, Frieda challenged policies that were constructed on unsubstantiated claims rather than facts and that, therefore, perpetuated prejudices and oppression. She lectured widely on issues of racial discrimination and the need for reason in politics, seeking to inspire her listeners to fight for substantive social and political changes. Often regarded as a woman ahead of her times, Frieda said in 1977, “I never considered myself a revolutionary.” Rather, she felt, she had “a moral obligation to be reasonable.”

Eventually, Frieda’s genius was acknowledged. In 1967, the American Association for the Advancement of Science named her a fellow, and the World Congress of Sociology dedicated a collection of academic essays, Language of Sociology, to Frieda in 1974, recognizing her dissertation research as groundbreaking work in the emerging field of sociolinguistics. She died in Helena in 1978.

Belle, who had again returned to Helena with her husband Norman Winestine in 1920 to raise their three children, continued to support women’s rights and humanitarian causes. She steadfastly lobbied the legislature on issues such as equal rights, child welfare, and education until her death

in 1985. The vital importance of women’s issues—which Belle defined broadly as the essential concerns of humanity—and her belief that women possessed a greater capacity for reason than did men, prompted her to advocate for more women in positions of public office and political leadership. “The world needs a lot of straightening out,” Belle said.

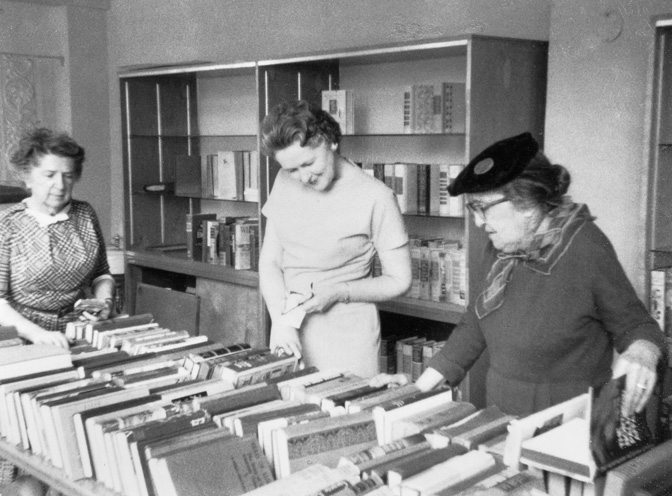

Both Fligelman sisters applied their ideals toward bettering their world. As lifelong leaders in the League of Women Voters and the American Association of University Women, Frieda and Belle helped expand women’s educational and political opportunities, while encouraging people to understand world affairs—such as oppression, economics, war, and peace—as essentially feminist issues. During World War II, they raised funds to sponsor Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. They later opposed both the Korean and Vietnam wars. After witnessing the failed military attempts to achieve lasting peace over the course of the twentieth century, Belle said in 1976 that diplomacy—not military action—was the only way to achieve long-term solutions. She added, “Reason is what we need!” LKF

Frieda and Belle were active in many local and regional reform efforts. Frieda worked for the Helena YMCA, and Belle supported efforts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendement. Belle worked alongside Frances Elge and Jeannette Rankin in the fight for women’s suffrage in Montana. Click the links for more information.

Frieda and Belle’s mother sewed a quilt which was eventually donated to the Montana Historical Society and features in Using Quilts as a Window into Montana History.

Sources

Brown, Bob. “Suffragists Fought to Win Montana Women’s Rights 100 Years Ago.” Independent Record, January 24, 2014, http://helenair.com/news/opinion/looking-back-at-a-pioneer-in-women-s-suffrage/article_a37ec2fc-88ba-11e3-b6a2-0019bb2963f4.html. Accessed September 22, 2014.

Butler, Amy. “Belle Winestine (1891-1985).” Jewish Women’s Archive. http://jwa/org/encyclopedia/artice/winestine-belle. Accessed September 22, 2014.

Fligelman, Frieda. Fligelman interview by Kathryn Kress, 1976. Oral History 615, General Montana History Collection, Montana Historical Society Archives, Helena.

____________. Frieda Fligelman Papers, 1927-1984. Mss 184. Archives and Special Collections, Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula.

____________. Notes for a Novel: The Selected Poems of Frieda Fligelman. Rick Newby and Alexandra Swaney, eds. Helena: Drumlummon Institute, 2008.

Giles, Ken. “Behind the Doors of ‘Academe’ Is Freedom at Work.” Independent Record, January 16, 1977, 31.

Olds, Virginia. “Jeannette Rankin Recalls Fight for Woman Suffrage in State.” Independent Record, August 9, 1964, 1, 3.

“She is No Longer ‘Transparent.’” Billings Gazette, May 1, 1975, 18.

Winestine, Belle Fligelman. “Mother Was Shocked.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 24, no. 3 (Summer 1974), 70-79.

_____________. Winestine interview by George Cole, 1976. Oral History 87, General Montana History Collection, Montana Historical Society Archives, Helena.

Winestine, Norman and Belle. Norman and Belle Fligelman Winestine Collection (1895-1986), Manuscript Collection 190, Montana Historical Society Archives, Helena.

“Women Plan MSU Symposium.” Billings Gazette, March 29, 1973, 28.

Wynn, Lee. “Frieda Fligelman: A Garland for Her Crown.” Independent Record, June 30, 1968, 30.

_____________. “Looking In on the Arts.” Independent Record, April 21, 1968, 16.