Homesteading was hard work, but it offered single women a chance to become independent at a time when social mores made it difficult for women to be self-sufficient. Among the many single women who took this opportunity were two African American women who filed homestead claims and did well for themselves. Homesteading allowed Annie Morgan and Bertie Brown to become women of property, and each brought special skills to the communities in which they settled.

Nothing is known about Agnes “Annie” Morgan’s early life except that she was born in Maryland around 1844. By 1880, she was married, had come west, and was a domestic servant in the household of Capt. Myles Moylan and his wife, Lottie. The captain was stationed at Fort Meade, Dakota Territory, along with Frederick Benteen and other survivors of the Seventh Cavalry at the Battle at Little Bighorn. Morgan’s association with the Seventh Cavalry lends credence to the legend that she once had cooked for Gen. George Armstrong Custer.

Sometime after 1880, Morgan, by then a widow, made her way to Philipsburg in Granite County. County attorney David Durfee hired her to care for his uncle who had a severe drinking problem and was very ill. Durfee arranged for Morgan to take his uncle to an abandoned farm on Upper Rock Creek to dry out. There, she cared for the man and brought about an extraordinary cure. When he eventually went his own way, she stayed on at the farm, filing a homestead claim.

One day in 1894, Morgan happened upon Joseph “Fisher Jack” Case lying on the banks of Rock Creek, gravely ill with typhoid. Case was a Civil War veteran from New Jersey who made a living catching fish to sell in Philipsburg. Morgan nursed him through the often-fatal illness. To repay her kindness, Case fenced Morgan’s homestead. The pair developed a mutual affection, and when the fence was done, Case stayed on at the homestead. Morgan died in 1914, and she is buried in the Philipsburg cemetery.

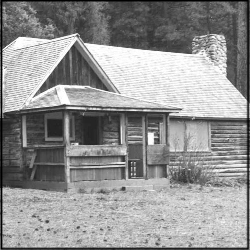

The Forest Service beautifully restored Morgan’s cabin. In the process, workers discovered a curious object hidden in the upper door frame. Bits of red string, a soap wrapper, and other items consistent with the bundles carried by African root doctors suggest that perhaps Morgan carried these traditions, handed down to her from family members, to the Montana frontier. She certainly proved her skills at doctoring. The Morgan-Case Homestead is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and in 2013, Annie Morgan was accepted into the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame.

Bertie Brown, born in Missouri, came to homestead in Fergus County. She was in her twenties when she settled in the Lewistown area in 1898. She later homesteaded along Brickyard Creek, filed her claim in 1907, and proved up in 1912.

Brown described herself at different times as an abandoned woman and as a widow. Like many women homesteaders, she supplemented her income in various ways. She raised leghorn chickens, kept a garden, and planted wheat, oats, and barley on twenty-five acres of her homestead. She is, however, best remembered for her moonshine.

During the 1920s, the rutted road to Brown’s place was familiar to many Fergus County locals and to others who had heard of her famous brew. When Prohibition outlawed alcohol, many made their own moonshine and sold it illegally. Bad hooch, however, could cause blindness and even death. Those looking for a place to party away from the eyes of the revenue officer knew to point their cars toward Black Butte and Bertie Brown’s place. Her still—according to locals—produced some of the best, and safest, moonshine in the country. Brown carved a niche for herself. The tidy homestead where she lived with her cat was a place of warm hospitality.

In May 1933, just months before the end of Prohibition and Brown’s main livelihood, the revenue officer came around and warned her to stop her brewing. Brown also took in dry cleaning, using gasoline as the cleaning agent. As Brown multitasked, dry cleaning some garments and tending what would be her last batch of hooch, the gasoline exploded in her face. She died of her injuries some hours later.

While Montana was not immune to racism and discrimination, and African American Montanans endured these undercurrents, both Annie Morgan and Bertie Brown were women beloved by their adopted white communities. The true stories of Morgan’s skilled healing and Brown’s “safe” moonshine have been passed down by those who knew them. These stories live on in local lore. EB

Learn more about Annie Morgan’s homestead by visiting our Places page.

If you’re interesting in Montana women’s influence on agriculture, you may enjoy reading “A Farm of Her Own” and “The Work Was Never Done: Farm and Ranch Wives and Mothers.”

Sources

Baumler, Ellen. “Bertie Brown.” Montana Moments Blog. Accessed December 1, 2013.

___. “Annie Morgan.” Montana Moments Blog. Accessed December 1, 2013.

Hagan, Delia, and Janene Caywood. Morgan-Case Homestead. National Register of Historic Places Nomination, State Historic Preservation Office, Helena, Montana. Accessed December 1, 2013.

Inbody, Kristen. “The Sagas behind Montana’s Remote, Crumbling Homesteads.” Great Falls Tribune, August 7, 2011.

Puhek, Lenore. “Annie Morgan.” Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame, District 12, 2013 Hall of Fame Inductees. Accessed December 1, 2013.