Evelyn Cameron (1868-1928) and Julia Tuell (1886-1960) were two women with similar talents but opposite perspectives. Each left an invaluable photographic record of life and culture in eastern Montana. Each was an artist in her own right, and because the work of each is so different, the two complement each other remarkably well.

Terry, Montana, on the state’s eastern edge, was home to Evelyn Cameron, who documented women in particular in both traditional and nontraditional roles on ranches and homesteads during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Cameron’s photographs capture the spirit of the West with shutter, lens, and expert eye.

Evelyn Cameron came to Montana from England with her husband, Ewen, to raise polo ponies, an enterprise that failed. While Ewen was a noted ornithologist and never actively worked on the ranch, Evelyn quickly learned to milk cows, break horses, and cultivate a garden. When they needed money, Evelyn learned the art of photography. She sold photographs, especially portraits, of neighbors. She also sold produce and took in wealthy boarders to support herself and her husband.

As a professional photographer, Cameron traveled to area homesteads and ranches, capturing ranch life. And she was always ready to pitch in. Once, for example, while photographing the Burt family’s annual sheep shearing, a measles epidemic broke out, devastating the family. Cameron stayed with the Burts for several weeks, sleeping on an uncomfortable cot, nursing sick children, doing chores, shearing sheep, and cooking.

Cameron’s photographs include ranch wives, single women homesteaders, and immigrant groups, especially German Russian women who came to Montana after the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909. Her photographs show that women worked as hard as men, but they also show shared work and play and the joys of ranching and homesteading.

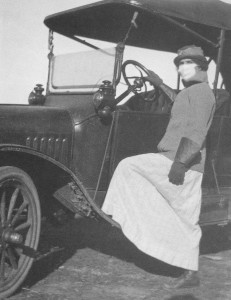

Cameron was fearless and practical. For instance, she helped pave the way for other ranch women by adopting the scandalous divided riding skirt. At a time when women never rode astride, Cameron believed sidesaddle was unsafe unless the horse was a slow nag. And living forty-eight miles from Miles City, she could not afford to ride a slow nag into town.

After her death, Cameron’s photographs lay undiscovered until the late 1970s, when Time-Life editor Donna Lucey stumbled upon eighteen hundred photo negatives and twenty-seven hundred original prints, stored in a basement in Terry. Lucey studied Cameron’s meticulously kept diaries and photographs. Her book, Photographing Montana 1894-1928, revealed many of these photos for the first time and made the photographer a Montana icon.

Julia Tuell’s work is much less well known than Cameron’s. Tuell photographed Montana’s Northern Cheyennes and the Sioux of South Dakota in the early twentieth century. Through her camera lens, Tuell recorded details she must have known would someday be of great value.

Julia Toops was sixteen in 1901 when she married forty-three-year-old teacher P. V. Tuell in Kentucky. The couple headed west where P.V. had a job teaching Indian children. By 1906 on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation at Lame Deer, Montana, Julia Tuell had begun recording images of the Plains Indians at a time of agonizing change. Traditional skills were still very much a part of reservation life, and the transition to agriculture was a struggle. Tuell carried her unwieldy Kodak glass-plate camera and tripod on horseback, in a buggy, and later in an old Model T.

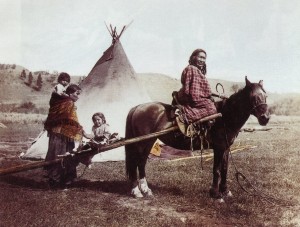

With her own four small children in tow, Tuell captured intimate details: Cheyenne women scraping hides and roasting dogs (a food staple), dogs and horses hitched to travois, babies in their cradleboards, chiefs in full regalia, and children at play. On the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, Tuell continued her photographic journal. Her photographs poignantly parallel those of Evelyn Cameron, who so beautifully documented eastern Montana homesteading. However, Tuell’s images capture the opposite perspective, documenting the people who saw their lives turned upside down with the tilling of the prairie sod. Her work is a pictorial tribute to the people of the plains.

The photographers’ motivations and cultural background account for the striking differences in Cameron’s and Tuell’s work. Because Cameron found it easy to enter into the daily lives of the people she photographed, and because they embraced the opportunity to pose for her, her subjects appear natural and at ease. On the other hand, Tuell’s subjects often appear stiff and uncomfortable. Nevertheless, Tuell’s portraits provide a rare glimpse of a culture in transition and underscore both the Northern Cheyennes’ and the Lakotas’ commitment to maintaining their traditions. That Tuell was allowed to photograph ceremonial activities reveals an unusual relationship between the photographer and her subjects.

Like Evelyn Cameron’s photographs that came to light long after her death, Julia Tuell’s work was also unknown until her son Varble brought them to the attention of Bridger High School teacher Dan Aadland in the late 1970s. And also like Cameron’s photographic portfolio, Tuell’s includes some remarkable self-portraits and images of herself engaged in her work. One stunning image shows her dedication as she photographed a Northern Cheyenne Sun Dance in 1909. She stands behind her bulky Kodak camera and tripod, two weeks before she delivered her third child.

These two pioneer photographers left very different but equally stunning legacies. Their work captures moments in time and lifestyles that the printed word alone can neither adequately nor fully interpret. Thanks to their important work, ranching, homesteading, and contrasting Native lifestyles teach us valuable lessons about progress, its advantages, and its price. EB

Want to learn more about Evelyn Cameron? Read her diaries and see her photos in this online exhibit.

The 2014 Montana Historical Society calendar features Evelyn Cameron’s photography. You can purchase a copy by clicking here.

Sources

Aadland, Dan. Women and Warriors of the Plains: The Pioneer Photography of Julia E. Tuell. New York: Macmillan, 1996.

Davidson, Gerald. Book review of Women and Warriors of the Plains. In Montana The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 49, No. 1 (Spring, 1999), 79.

“Evelyn Cameron.” Vertical Files, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Lucey, Donna. Photographing Montana 1894-1928: The Life and Works of Evelyn Cameron. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991.