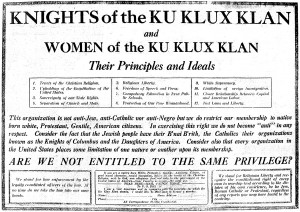

In the 1920s, a group of women banded together under the auspices of a shared political belief and religious background. They dedicated themselves to installing memorials in their communities, hosting family picnics, and delivering flowers to local hospitals. In many ways they resembled other civic organizations of their time, many of which served a social function by bringing women of similar interests together. Committed to “tenets of the Christian religion,” “freedom of speech and press,” and “the protection of pure womanhood,” the ideology of this group overlapped with other groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Yet their commitment to “white supremacy” separated the Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK) from other women’s organizations—and provides a reminder that female participation in politics was not always a progressive force.

At its height, in the 1920s, the Montana Realm of the Ku Klux Klan boasted fifty-one hundred members across more than forty chapters. Committed to what they called “100% Americanism,” KKK members espoused xenophobic policies against immigrants and racist policies against nonwhites, and fostered hatred toward Jews and Catholics. In a Montana suffering from economic downturn, rapid technological advances, drought, labor unrest, and a generally chaotic postwar period, the Klan provided an appealing organization for those looking for scapegoats.

The Klan’s anti-vice platform and its promise to protect white womanhood may have particularly attracted the women who joined its ladies’ auxiliary. A full-page KKK ad in the Billings Gazette declared “our hostility to bootleggers, professional gamblers, and all forms of organized and commercialized lawlessness or vice is unlimited.” For members of the WKKK, the recently won right to vote became a tool for promoting both the KKK’s nativist policies and the “social housekeeping” agenda they shared with other women’s groups like the WCTU. Over a million women joined the WKKK nationally, and their rhetoric focused on protecting the home and white womanhood.

In Montana, the KKK and WKKK emphasized anti-Catholicism in their rhetoric and politics. Central to their mission was a campaign for compulsory public education to stem the influence of parochial schools. This focus on education gave WKKK members another reason to support the organization. Women and men alike had long seen education as a “women’s issue”; in fact, Montana women had voted in school elections since 1887 (twenty-seven years before they won equal suffrage), and working to influence educational policy continued to provide an appropriate political outlet for Montana women.

The Klan’s involvement in social issues was rooted in its racist, anti-Catholic ideology. The WKKK’s constitution, for example, declared that the organization “shall ever be true to the maintenance of White supremacy and will strenuously oppose any compromise thereof.” Montana’s WKKK members embraced this stance. In 1928, Mrs. D. Cohn, a seventy-one-year-old resident of Butte, sent Montana’s “Grand Dragon” a token of the Catholic presidential candidate, Al Smith, in a coffin. Other WKKK members in Billings, Roundup, Harlowton, and Livingston attended cross burnings, organized boycotts, and proudly displayed their Klan affiliation—although the acceptability of women wearing men’s regalia came into question during discussions about organizing a 1927 parade in Whitehall. WKKK members also attended Klan rituals such as funerals and, like their national counterparts, took on the traditionally female role of providing costuming and food for social events and secret gatherings.

Klan members met their share of antagonism from other Montanans. In Butte, where immigrants, many of whom were Catholic, made up a considerable portion of the population, Sheriff Jack Duggan reported: “Our men have orders to shoot any Ku Kluxer who appears in Butte.” Elsewhere, however, Klanswomen presented themselves as a respectable alternative to other area women’s clubs, and reporters were sympathetic; one Billings Gazette article recorded the WKKK delivering flowers to the hospital.

By the end of the 1920s, the Klan’s influence waned, both in Montana and nationally. The Klan had failed to stem Montana’s prolific bootlegging, and a national backlash against the KKK hurt local chapters as well. Butte’s chapter of the Klan folded in 1929; state Klan records exist only until 1931. Klan propaganda continued to circulate in the state, but membership dwindled to a few isolated groups whose racist rhetoric sporadically appears in Montana communities today, usually in the form of pamphlets and broadsheets. KB

Sources

Blee, Kathleen M. Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

Erickson, Christine K. “‘Kluxer Blues’: The Klan Confronts Catholics in Butte, Montana, 1923-1929.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 53, no. 1 (2003), 44-57; JSTOR, Web, August 1, 2014.

Johnston, H. W. “Historical Note.” Guide to the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, Butte, Montana, Records Finding Aid, 1995, Northwest Digital Archives.

KKK advertisement, Billings Gazette, September 30, 1923.

Ku Klux Klan Vertical File, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Sturdevant, Anne. “White Hoods under the Big Sky: Montanans Embrace the Ku Klux Klan.” In Dave Walter, ed., Speaking Ill of the Dead: Jerks in Montana History. Guilford, Conn.: Globe Pequot Press, 2011.

Women of the Ku Klux Klan. Constitution and Laws of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan. First Imperial Klonvocation at St. Louis, Missouri, January 6, 1927.