Founded in 1883, the Montana chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was a popular, well-organized women’s club focused on reducing the consumption of alcohol in the state. Part of a broad series of reform movements that swept the country at the turn of the century, the WCTU was witness to women’s growing political power in the area of social reform.

The national WCTU was founded in Ohio in 1873 and quickly gained a broad base of support around the country. Like their national counterparts, Montana women joined the WCTU because they believed that limiting access to alcohol would in turn reduce the incidence of other social ills, such as gambling, prostitution, and public and domestic violence. In addition to advocating temperance (and later complete prohibition), Montana WCTU members also worked for a broad range of social reforms. At their state convention in Billings 1910, for example, the members voted for resolutions that “urged enforcement of juvenile court law [and] government aid to destitute mothers, . . . condemned the use of coca-cola, and recommended sanitary fountains.”

In her study of the WCTU and similar women’s clubs in this period, historian Stephenie Ambrose Tubbs argues that Montana women enjoyed a “growing sense of social and political power through their clubs’ active participation in social and civil affairs.” By asserting their role as reformers, the middle-class women involved in the Montana WCTU were restructuring ideas about femininity and women’s role in the public sphere. They challenged the traditional idea that a woman’s place was in the home, suggesting instead that society had become so morally corrupt that it required women’s political participation. They drew on the Victorian idea of women’s natural moral superiority to make the case that women had to take the lead in reform.

Elizabeth Fisk, wife of the editor of the Helena Herald, Robert Emmett Fisk, expressed the idea that “perfect womanhood” required moral uprightness and self-sacrifice: “I never yet fully realized what it is to be a true, whole-souled, woman,” she said. “Such capacities of doing, being, and suffering, such striving for the good and pure, not only, or chiefly, for ourselves, but for those whom we love.”

Like many Montana women, Fisk’s belief in the social responsibility that came with women’s moral superiority drove her to become actively involved in the temperance movement. She was especially enraged after the wedding of Irish businessman Thomas Cruse, where free-flowing liquor led to incidents of public drunkenness around Helena. She wrote of the rowdy fete, “It ought to arouse every mother in the city to fight for her boys, her ‘God and Home and Native Land.’”

To enable female reform, the WCTU included suffrage as part of its political agenda. The organization’s leaders believed that the vote was a crucial tool for enacting social change and that reforms like prohibition would have a greater chance of success if women had the franchise. Thus, they argued for women’s right to vote as a social necessity rather than a natural right.

In spite of the WCTU’s pro-suffrage stance, historian Paula Petrik points out that some Montana suffragists actually worked to distance their cause from the temperance movement. Knowing that prohibition was a controversial issue, leaders of the Montana Equal Suffrage Association hoped to avoid alienating men (and some women) in the community who might otherwise be inclined to support the vote. This rift did not go unnoticed by Montana WCTU members. Mary Alderson, leader of the organization’s suffrage campaign, later recalled: “We had another suffrage organization auxiliary to the National Woman Suffrage Society. Its leader told me not to dare to bring prohibition into the campaign. I was not taking orders.” “And,” she added, somewhat smugly, “the records . . . showed better results where the temperance issue was not camouflaged.”

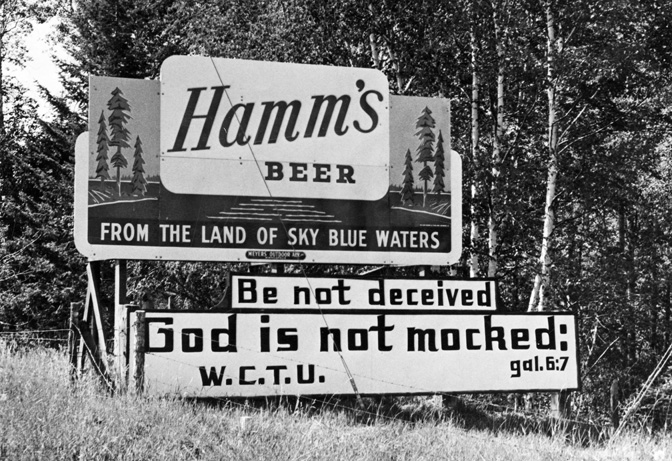

The WCTU followed its success in the 1914 suffrage campaign with a reinvigorated push for statewide prohibition. They joined forces with the Montana chapter of the Anti-Saloon League to demand a referendum on prohibition. With a strong base of support among homestead communities, the referendum passed overwhelmingly in November 1916, and the law went into effect at the end of 1918.

Thanks to the efforts of the members of the state’s WCTU, Montana was officially “dry” a full year before national prohibition became the law of the land. – AH

Not all women supported the WCTU’s aims. You can read about Montana women who profited from the illegal liquor trade in another entry in this series, “Montana’s Whiskey Women: Female bootleggers during Prohibition.”

Sources

Harvie, Robert A., and Larry V. Bishop. “Police Reform in Montana, 1890-1918.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 33, no. 2 (Spring 1983): 46-59.

Marilley, Suzanne M. “Frances Willard and the Feminism of Fear.” Feminist Studies 19, no. 1 (Spring 1993): 123-46.

Montana Woman’s Christian Temperance Union Records, 1883-1976. MC 160, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Helena.

Petrik, Paula. No Step Backward: Women and Family on the Rocky Mountain Mining Frontier, Helena, Montana, 1865-1900. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 1987.

Tubbs, Stephenie Ambrose. “Montana Women’s Clubs at the Turn of the Century.” Montana The Magazine of Western History. 36, no. 1 (Winter 1986): 26-35.

Tyrrell, Ian. “Temperance, Feminism, and the WCTU: New Interpretations and New Directions.” Australasian Journal of American Studies 5, no. 2 (December 1986): 27-36.