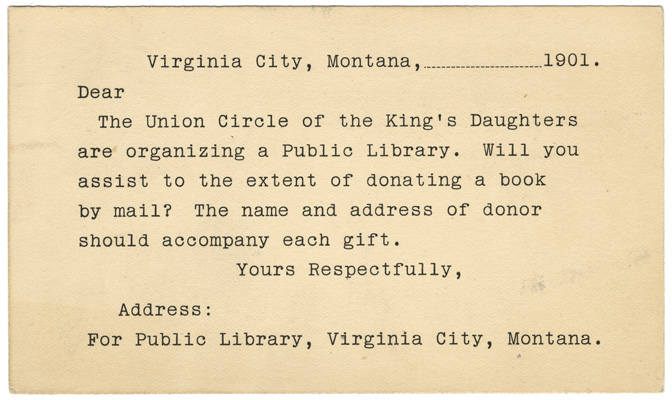

At the January 24, 1914, meeting of the Hamilton Woman’s Club, the club president “presented the idea of the Club boosting for [a] Carnegie Library building here.” Club members concurred and appointed a committee to urge city officials to act. Mrs. J. F. Sullivan, head of the club’s newly formed library committee, approached Hamilton’s city council about asking industrialist and library benefactor Andrew Carnegie for funds. After Marcus Daly’s widow, Margaret, donated the land for the building site, Carnegie’s secretary approved the city’s request. Two years later, the Hamilton Woman’s Club moved its meetings to a specially designated room in the town’s new Carnegie Library, an institution that owed its existence to the clubwomen’s hard work.

The Hamilton Woman’s Club’s instrumental role in the library’s construction is not an isolated case. During the Progressive Era, women’s voluntary organizations frequently led community efforts to build public libraries. In 1933, the American Library Association estimated that three-quarters of the country’s public libraries “owed their creation to women.” More recently, scholars Kay Ann Cassell and Kathleen Weibel have argued that “women’s organizations may well have been as influential in the development of public libraries as Andrew Carnegie,” whose name is carved into thousands of library transoms across the United States.

Since the time of white settlement, Montanans seem to have been unusually passionate about books and libraries. In an 1877 edition of the Butte Miner, one writer noted, “The need for a library was felt here last winter, when aside from dancing there was no amusement whatever to help pass the long, dreary evenings. Dancing, in moderation, will do very well, but it is generally allowed to have been somewhat overdone last winter . . . this library scheme . . . will furnish a means of recreation . . . that is more intellectual and more to be desired in every respect.”

Rising to the call, women’s clubs founded libraries in communities across Montana. Most of these libraries started small: club members donated books, and a local milliner, dressmaker, or hotelier would offer shelf space. As the library (and the community) grew, it often moved to a room in city hall before, finally, opening in a separate building. By 1896 Montana could boast seven public libraries with collections of a thousand volumes or more, and the State Federation of Women’s Clubs maintained a system of traveling libraries. Continue reading Progressive Reform and Women’s Advocacy for Public Libraries in Montana