The adage “behind every successful man stands a good woman” has become an outmoded cliché. Nonetheless, it remains remarkably true for Montana’s favorite son, cowboy artist Charlie Russell, whose wife, Nancy Cooper Russell, was instrumental in his success. In fact, while Nancy “stood behind” her husband in terms of providing nurture and support, when it came to managing the business aspects of his career—and earning him international fame in the process—she was fully out front. As Charlie’s nephew, Austin Russell, noted, “[S]uccess came tapping at the [Russells’] door or, rather, Nancy dragged success in, hog-tied and branded.”

Nancy Cooper Russell’s story would in many ways befit a Horatio Alger novel. She was born in 1878 into meager circumstances on a Kentucky tobacco farm after her father, James Cooper, had abandoned her then-pregnant mother, Texas Annie Mann. In 1890, Nancy moved to Helena, Montana, with her mother, half-sister, and her mother’s second husband, James Allen. Thereafter, Allen was most often absent, so Texas supported her daughters by taking in sewing and laundry. Eventually, Nancy hired out as a housekeeper as well.

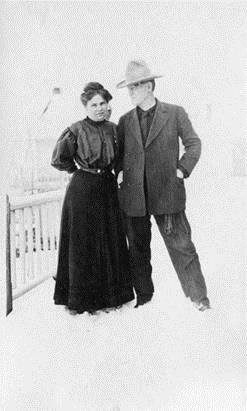

Texas died in 1894 following a lengthy illness. After the funeral, which Nancy arranged and paid for, Allen returned to Helena, staying only long enough to claim Nancy’s half-sister, Ella. He left sixteen-year-old Nancy to fend for herself. At the recommendation of one of her mother’s former customers, Ben and Lela Roberts—a Helena couple who had relocated to Cascade—hired Nancy to serve as their live-in housekeeper and help care for their three young children. Years later Nancy would recall her excitement when, in the fall of 1895, she learned that the Roberts were expecting a special dinner guest: a former cowboy who had an established reputation as both an artist and a hellion. Eleven months later, Charlie and “Mame,” as he always called Nancy, were married in a ceremony held in the Roberts’s home. The following year, the newlyweds moved permanently to Great Falls believing that the larger city would offer them greater opportunities.

Charlie’s marriage to Nancy marked a turning point in the artist’s career. Uncomfortable selling his art, Charlie had historically undercharged customers for his work. Nancy did not share his discomfort and, with Charlie’s encouragement, soon took control of the business aspects of his career. As Montana poet Grace Stone Coates observed, “Russell didn’t want to . . . run after moneyed people to buy his pictures; and Nancy wanted to cash in on her husband’s talent; both were right.” Within a few short years, Nancy was demanding and receiving thousands of dollars for Russell’s oil paintings, sums Charlie decried as “dead men’s prices.”

In addition to courting individual collectors, Nancy arranged exhibitions in such distant venues as Calgary, Winnipeg, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, London, and New York. For Nancy, art was business and she left nothing to chance. According to Russell scholar Brian Dippie, in addition to locating willing galleries and working with their owners, Nancy organized “advance publicity . . . planted [articles] in the local papers” and held her own “in business negotiations over commissions, copyrights and prices for direct sales.”

The drive that made Nancy so successful professionally did not serve her as well in her personal life. She refused to associate with Charlie’s closest friends—cowboys and drinking buddies from his early years on the range—whom she viewed as a hindrance to his career. In response, these men resented Nancy and were vocal in their disapproval of the young woman whom Austin Russell described as “smart as a steel trap and as quick as the lash of a whip.” In turn, although she longed to be accepted in the elite social circles of Great Falls, society matrons snubbed Nancy for her unprivileged beginnings. She suffered bouts of depression throughout her life, and her demanding nature ultimately alienated her only child, Jack Cooper Russell, whom she and Charlie adopted as an infant in 1916.

Following Charlie’s death in 1926, Nancy moved permanently to Southern California where she, Jack, and Charlie had been wintering since 1920. She devoted her efforts to promoting Russell’s legacy, organizing memorial exhibits of his work, and publishing two books of his writings—Trails Plowed Under, an anthology of cowboy yarns in 1927, and Good Medicine, a compilation of his illustrated letters in 1929. And she donated Russell’s beloved log-cabin studio and its contents to the City of Great Falls to serve, in her words, “as a permanent record . . . [memorializing] the love of a great man for a big country and its people.” She died in Pasadena in 1940 after several years of ill health.

Nancy was by no means singular in terms of a being a woman who played a critical role in her husband’s success. The obstacles that she overcame in her youth and the status that she helped Charlie achieve, however, make her story truly notable. While she had many detractors among those who did not appreciate the changes that marriage brought to the former cowboy’s life, Charlie himself fully realized “Mame’s” contributions to his career. “My wife has been an inspiration to my work,” he once told a newspaper reporter. “Without her I would probably have never attempted to soar or reach any height, further than to make a few pictures for my friends and old acquaintances. . . . I still love and long for the old west, and everything that goes with it. But I would sacrifice it all for Mrs. Russell.” KL

Want to learn more? Read Brian Dippie’s article, “‘I Want It Real Bad’: The Charles M. Russell-Mackay Collaboration,” published in Montana The Magazine of Western History 54, no. 2 (Summer 2004): 32-55. You can find links to the full text of all Montana The Magazine of Western History articles relating to women’s history here.

Sources Dippie, Brian. “Charles M. Russell: The Artist in His Prime.” In The Artist in His Heyday. Santa Fe, N.M.: Gerald Peters Gallery, 1995: 13-22.

Grace Stone Coates to James R. Rankin, December 16, 1936. James Brownlee Rankin Papers, Montana Historical Society, MC162, Box 1, Folder 7, Helena.

Russell, Austin. C. M. R.: Charles M. Russell Cowboy Artist. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1957.

Russell, Nancy. “Biographical Note,” In Charles M. Russell, Good Medicine: The Illustrated Letters of Charles M. Russell. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1930: 15-23.

Stauffer, Joan. Behind Every Man: The Story of Nancy Cooper Russell. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011.

Taliaferro, John. Charles M. Russell: The Life and Legend of America’s Cowboy Artist. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003.

I believe I have a piece of Art from Mr. Russell, painted in 1922.

Anybody interested?

I have 4 painting or prints it has is name and a buffalo head . One picture on the back has buffalo hunt. The second one on the back has Upper Missouri 1840 and a date 1902 The third one has on the back Attack on the red river carts 1903. The fourth one has Plateau marauders 1902 . Thank You If You could reply

I’m not sure what type of information you are interested in, but I encourage you to contact someone on our museum staff. You might start with Amanda Streeter Trum, Curator of Collections, (406) 444-4719, Email: atrum@mt.gov. I’m sure she can direct you.

What a hero, God bless their souls! What happened to Jack? In honor of the life that CMR loved! I’ll say, thank you God for the crazy good life and all the love from the Blackfeet people my friends, and country. Amen. (In Amskapi Pikunni). Kitsimah Apistookii for the Owasopsii Iksukapi life and sukapi kissikomimm from the AmskapiPikunni Nitsitopi my Nitaka’s Un’ya